Editor’s note: This is part three of a four-part series about the prospects for “growth machine” coalition politics under presumptive Mayor Cherelle Parker, which looks at some pro-housing policies that could unite the different constituencies with a shared interest in more economic growth, jobs, and tax revenue.

City housing policy is a topic that tends to generate a lot of heated debate, but across the more practical corners of Philadelphia’s housing advocacy landscape there’s a broad consensus around an agenda of “supply, stability, and subsidy.”

While there are some genuine and important disagreements about the particulars, there’s also a lot of general agreement that public policy should aim to increase housing inventory, while also increasing stability for tenants and low-income homeowners, and at the same time increasing public funding for purpose-built, regulated affordable housing, home repair grants and so on.

The “supply” leg of this agenda has been badly neglected during Mayor Kenney‘s two terms in office, with administration housing officials mostly content to let the 10-year tax abatement — and later the abatement policy cliff in 2021 — drive most of the action on market-rate and mixed-income housing. What’s needed going forward is a positive, focused agenda for housing supply specifically.

A handful of City Council and Kenney administration efforts moved the needle in the pro-housing direction somewhat, to be fair, such as former 7th District Councilmember Quiñones Sánchez’s Mixed-Income Housing density bonus program, the updated plumbing code, the “51/49” program for mixed-income housing on Land Bank land, and the Turn the Key program. But there was never a lot of momentum behind doing things to broadly increase housing production in general.

Much more often, the balance of City Council housing legislation has been pushing in the opposite direction. During Mayor Kenney’s two terms, Council became increasingly inventive about finding new ways to inhibit infill housing through the abuse of zoning overlay districts. The goal of such legislation has often been to ban lower-cost market-rate housing types like apartments, duplexes and triplexes, single-room-occupancy buildings, and accessory dwellings — in direct contrast with the growing housing advocacy world consensus that the city should do less to regulate these Missing Middle building types.

Much of the policy action on housing supply from the 2015 to 2023 City Council could be summarized as a backlash against many of the overall-positive trends resulting from the earlier 2007-2012 Zoning Code Commission (ZCC) reforms that were designed to ease the way for more by-right infill housing construction. With the Growth Machine coalition’s political stock rising after the 2023 election, the term beginning in 2024 presents an opportunity to get the pro-housing agenda back on track.

What are some of the housing advocacy priorities that belong on the Growth Machine coalition’s agenda?

Citywide laws and policies — not District overlays

The most important thing for getting the wheels back on the pro-housing policy agenda in 2024 is reasserting the validity of passing citywide housing laws again.

During the Kenney years, housing politics mostly devolved into a series of Council District-level conversations aside from a few higher-profile bills like the Mixed-Income Housing density bonus program. But even that program was weakened by a legislative push from the Kenney Planning Commission, and then weakened further still through the use of zoning overlays by district Councilmembers, such as one from Council President Darrell Clarke that made those density bonuses illegal to use in the 5th Council District.

Even though Philly has always had a strong tradition of councilmanic prerogative, the trend of using zoning overlays for more routine business has been uniquely corrosive to city planning in a path-breaking way that’s gone under-appreciated.

For another recent example, former At-Large Councilmember Derek Green received a lot of positive local and national media attention last spring when he introduced a bill re-legalizing single-room occupancy housing citywide, signaling there might be some appetite for citywide legislation again. But then Council President Clarke wouldn’t even refer the bill to the Rules Committee for a hearing. And according to City Hall sources, multiple District Council members were preparing zoning overlays to nullify the law in their districts in the event that it would pass.

The persistence of this “planning nullification” trend on City Council strongly suggests that state government is the better venue for passing pro-housing laws at this point, although there are still some worthy causes in this vein that are worth taking up in City Hall too.

State-level zoning reform

City-level campaigns for citywide housing policy changes around transit-oriented development, more housing in high-opportunity areas, and other Missing Middle housing types are important for bringing together the relevant coalition stakeholders to work together and perform the pro-housing politics we want to see in Philadelphia in a more visible way for the news media. It’s even possible there could be some legislative wins as a result.

But given the realities of councilmanic prerogative and the reactionary NIMBY politics that have taken hold in many Council Districts, along with the relatively weak hand the mayoral administration has to play in setting land use policy, it’s important to be realistic about the prospects for success.

The dystopian reality is that any District Councilmember can opt their district out of almost any positive citywide changes that the growth machine coalition might want to make, through the use of zoning overlays and other nullification strategies.

That is why more of the political activity around pro-housing should move to the state level instead, with sustained lobbying and advocacy campaigns aimed at creating more state guardrails around the zoning tools that are available to Pennsylvania municipal governments and defanging most of the common tactics municipal officials use to suppress infill housing and commercial development.

In red, blue, and purple states across the U.S., state-level elected officials are taking action to increase housing production by cutting through the tangle of municipal rules and regulations designed to make the housing approval process as discretionary and unpredictable as possible.

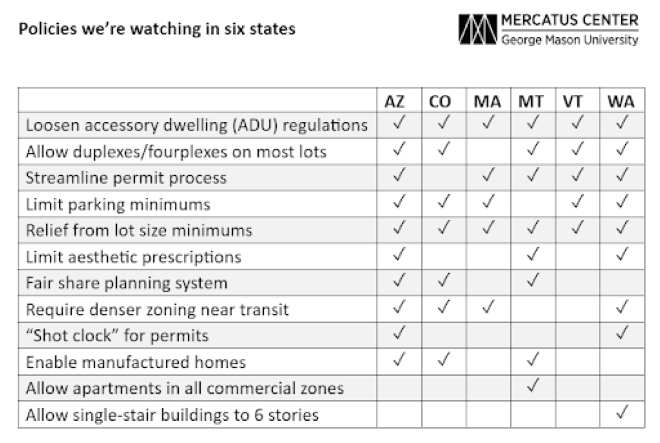

There is now an impressive body of state legislation on this front, almost all of which has passed on a bipartisan basis, doing things like broadly re-legalizing Missing Middle housing types, requiring municipalities to allow buildings up to six stories or more near transit stops or in commercially-zoned areas, relieving builders from unaffordable parking mandates, preventing municipalities from setting excessively large lot size rules, and more.

The Washington, D.C.-based Mercatus Center has been tracking the status of state-level pro-housing legislation across the U.S. and there are some noticeable patterns with the kinds of bills that have been passing. This chart omits some pretty significant success stories from California, Oregon, Connecticut, and Massachusetts, but provides a good sense of the wide variety of political contexts in which these bills are succeeding.

There are some early signs that these ideas have a constituency in both parties in the Pennsylvania legislature, as well as in some different corners of the housing advocacy world across the state. This is an area of policy that the Philadelphia-area growth machine coalition organizations should consider spending more time and resources on because it could help resolve some of the municipal-level problems these various actors are having with Philadelphia City Council and towns across the region.

Philadelphia City Council’s overlay mania trend now cannot be resolved at the municipal level unless some District Councilmembers change their minds about things, but state-level actors could try to win statutory changes or lawsuits to constrain what can be done with zoning overlays in the first place.

And for all the well-deserved guff that Philly elected officials get for their bad behavior in this area, the suburban municipal officials across Pennsylvania are very often the worst actors. Lower Merion officials are ready to cancel plans to allow buildings up to six stories in downtown Ardmore despite high regional housing costs and low inventory. Upper Gwynedd Township officials might deny a modest 60-unit LIHTC project right next to their regional rail station because some neighbors dislike the density. And in Plymouth Meeting, mall owners can’t get the Township officials to seriously engage on rezoning the Plymouth Meeting Mall parking lot for dense housing.

Even when municipal governments try to do a little better, they still end up using a “conditional use” standard of review for large projects where there’s a very wide scope for political meddling and bad-faith delay tactics.

While Philly has its own housing governance issues for the state to fix, in general, the goal should be moving the rest of PA closer to a true by-right permitting regime like Philly has, where there are clear rules for what can be built which roughly correspond to what is buildable in reality, and where zoning-compliant projects can get over-the-counter permits without having to worry about winning a popularity contest.

If changes to state law can make dense housing and commercial development buildable by-right on commercial land and land close to transit stations throughout the city and region, builder interests could be looking at decades’ worth of demand for construction jobs throughout the region.

None of this obviates the need for pro-growth coalition activity aimed at Philadelphia City Council, however, which still matters for bringing together the relevant interest groups and starting to change the political calculus for city elected officials. It is important for the Growth Machine coalition to take a two-pronged approach, since any local efforts will be made materially easier if Pennsylvania can pass similar pro-housing laws as other states.

Stay tuned for our next installment in this series, looking at the local-level housing policy changes that could unite the growth machine coalition in 2024.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

![]() MORE FROM JON GEETING

MORE FROM JON GEETING