We clearly understand bread’s importance as a building block of civilization, its symbolic centrality to the world’s religions, and its contribution to human nutrition. Yet bread, for most people, is not a terribly exciting topic.

“Bread is incredibly important,” says Alex Bois. “On the other hand, it’s fucking bread, mundane and unimportant. It’s a functional part of the meal. It’s filler.”

It is a little surprising to hear Bois speak of bread in these terms. His company, Lost Bread Co., is one of several in Philadelphia which has made bread very exciting and very important. His social-justice business goals—living wages for workers, waste reduction, and the focus on milling local organic grains—offers a shining model for food companies here and around the country.

Lost Bread’s social-justice business goals—living wages for workers, waste reduction, and the focus on milling local organic grains—offers a shining model for food companies here and around the country.

But Bois’ approach shows that baking bread the right way can also be fun. Along with the expected multi-grain, Italian-style pane da tavola and deli rye, are creative breads like cranberry pepita, olive citrus, and a rye made with roasted beets. The freshly-milled ancient-grain flour creates a depth of flavor unlike that of other loaves. And then there’s Lost Bread’s preztel shortbread—made sustainably with leftover sourdough pretzels—which was called “The Cookie of the Future” by Food & Wine and last month was named New York City’s “Best Cookie.”

Buy local, sustainable breadDo Something

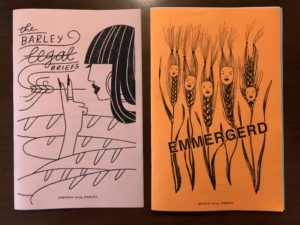

Lost Bread’s amazing monthly grain share introduces customers to products made with lesser-known ancient grains (March was emmer; April is spelt), along with fun monthly classes to teach customers how use the grains in their own baking. (In March, Pasta Lab was invited in to teach students how to make emmer pasta). The Grain Share also includes a humorous ‘zine devoted to the monthly grain with gee-whiz history, puns, and recipes—January’s title: “The Barley Legal Briefs”; March’s title: “Emmergerd” (think “ermahgerd”).

“Grain Share is about awareness,” Bois says. But sourcing grain hasn’t been easy. “When I first got to Philly, it was damn near impossible to find local grain,” Bois says. Whole grains should be much cheaper than processed, commodity white flour, Bois insists. But the price of white flour is held artificially low. “We don’t want to cede control to large companies,” he says. Last year, Lost Bread bought over 40,000 pounds of grain from Mid-Atlantic farmers.

Creating a demand for alternative grains is way to preserve them and also to help grain farmers diversify for the future, as climate changes and other pressures mount. “It’s about the rich tapestry of how grain and bread supports the evolution of society,” Bois says.

“Bread feels so far behind other gourmet categories,” Merzbacher says. “When I started, I asked, ‘Can I take coffee and craft beer and apply those ideas to bread?’”

Lost Bread, which opened in 2017, is part of a small-but-growing movement of socially-aware breadmaking in the city. It’s also an example of good ideas coming from outside the city.

Bois came to Philadelphia in 2013 from New York, when he took a job with Ellen Yin and Eli Kulp as they were opening High Street on Market. Bois’ bread program was among the highlights at the acclaimed High Street. But in fall, 2016, Bois left. “The restaurant industry has a tendency toward exploitation,” he says. “There’s a lot of ills overlooked or accepted.”

Instead, he set out to create a business model in which he could offer to pay a minimum of $15-per-hour living wage. He now has nine full-time employees, with a tenth soon to start. The bakery recently moved into a large space at Craft Hall on Delaware Avenue, where Bois mills his own grain.

About the Foodizen seriesLearn More

In order to support that model, Lost Bread has sought to become more than a tiny, gourmet, mom-and-pop. It’s not all just high-end cranberry-and-pepita loaves. The daily bread is essential to the business. At High Street, Bois was selling bread at $10-$12 per loaf. Lost Bread is now around $5-$7 per loaf. “We knew a bakery like this wouldn’t work without scale,” he says. “Maybe it begins a luxury, but it begins to bleed into the fabric of everyday life. We want to be able to sell an affordable loaf of bread that’s tasty enough to get someone to eat whole grain.”

Lost Bread isn’t the only bread bakery looking to sell socially-conscious bread at scale. There’s also Fikira Bakery’s bread share CSA, run by 1149 Cooperative co-founder Ailbhe Pascal. Then there’s Bois’ friend, Pete Merzbacher, who owns Philly Bread, also started baking bread with goals of sourcing local flour and grain (he also came to Philly from elsewhere, in his case the Boston area). Famous for his Philly Muffin, a take on the English muffin, Merzbacher has chosen bakery locations in neighborhoods of the city that need new retail and job opportunities.

Merzbacher, who launched his business with a loan from Judy Wicks’s Circle of Aunts and Uncles, began baking in 2013 in a vacant storefront on revitalizing North Fifth Street. Recently he’s opened a larger bakery, with 14 employees, in the midst of Wayne Junction’s revitalization.

Articles from Foodizen by Jason WilsonRead More

“Scale and quality are not incompatible,” Merzbacher says. “Bread feels so far behind other gourmet categories. When I started, I asked, ‘Can I take coffee and craft beer and apply those ideas to bread?’”

That the answer, clearly, is yes, seems a sign of the times. Philly has always been a bakery town—beyond the South Philly staples of Amoroso’s and Sarcones, we have enjoyed first-wave artisan breadmakers like Metropolitan Bakery since the early 1990s. Like coffee, bread is finally having its second wave, in a way that is truly Philly. This is, increasingly, a place for experimentation, not just around flavors and restaurant concepts, but also sustainability, social consciousness and equity. How perfect, then, that it can all come together in the next loaf you pick up?

Jason Wilson is The Citizen’s 2019 Jeremy Nowak Fellow, funded by Spring Point Partners, in honor of our late chairman Jeremy Nowak. He is the author of three books, including most recently Godforsaken Grapes, series editor of The Best American Travel Writing, and writes for the Washington Post, New York Times, New Yorker and many other publications.

Lost Bread founder, Alex Bois. Photography by Anthony Pezzotti