Think for a moment about your experience on a typical pre-pandemic Election Day. Remember that woman or man who was standing outside the polling place offering copies of the “Official Democratic Party Ballot” to voters as they arrived? Chances are you didn’t see them this year—and you might not ever see them at your polling place again.

![]() A half-century ago, committee people were foot soldiers and ward leaders were generals in a powerful political army known as the Democratic City Committee.

A half-century ago, committee people were foot soldiers and ward leaders were generals in a powerful political army known as the Democratic City Committee.

The most effective committee people knew how to form and maintain strong working relationships with municipal government employees—from administrators to clerk typists—who could help them out in one way or another.

A capable committee person could get a street light replaced, get a pothole filled, or get a parking ticket fixed at a time when city-service requests from ordinary citizens might get lost in the bureaucratic swamp. And some ward leaders and committee people were part of the bureaucracy. They earned salaries in patronage jobs at City Hall while remaining politically active.

A half-century ago, committee people were foot soldiers and ward leaders were generals in a powerful political army known as the Democratic City Committee.

In the heavily populated row house blocks of mid-20th century Philadelphia, where everyone knew everyone else and some families stayed in place for generations, a good committee person could reliably deliver many controlled votes for the party ticket; and elected officials showed their appreciation by providing party activists with jobs and priority access to services.

However, this synergy weakened as the century neared an end. City population thinned out. Vacant houses and lots emerged on blocks that had previously been fully occupied. Families who left the city were replaced by newcomers who were more transient and not consistently supportive of the party ticket. Reduced federal funding and a declining tax base led to the elimination of many patronage jobs in city government.

Some agencies that had been patronage havens, like the clerk of quarter sessions, were eliminated, while others, like the Redevelopment Authority, underwent management reforms and leadership changes that made them resistant to politically-influenced hiring.

As a result, the current City Committee army, although far from powerless, now has much less capability to deliver winning turnouts for party-endorsed candidates.

In this year’s Democratic primary election, for example, Nikil Saval, a self-described Democratic Socialist and co-founder of Reclaim Philadelphia, won the nomination for state senate in the 1st Senatorial District, overcoming three-term incumbent Larry Farnese, whose family had been deeply rooted in the South Philadelphia Democratic Party infrastructure for decades.

In last year’s Democratic primary, veteran ward leader and City Councilmember Jannie Blackwell lost her seat to newcomer Jamie Gauthier. These victories were not razor-thin; both Saval and Gauthier outpolled their opponents in almost every ward within the districts in which they competed.

Last year, the party wasn’t even able to hold onto one of the lesser-known elective offices, the register of wills, which had been under City Committee control since Frank Rizzo’s day. South Philadelphia ward leader Ron Donatucci, who had presided over the office since 1980, lost to first-time candidate Tracey Gordon by four percentage points.

The prospects for reinvigorating the party are especially bad now, because Election Day is no longer just a date; it’s a streaming event. Under Act 77, approved by the Pennsylvania legislature last year, a voter may request and submit a mail-in ballot up to fifty days before the election date, giving our state the longest vote-by-mail period in the country.

In the heavily populated row house blocks of mid-twentieth century Philadelphia, where everyone knew everyone else and some families stayed in place for generations, a good committee person could reliably deliver many controlled votes for the party ticket; and elected officials showed their appreciation by providing party activists with jobs and priority access to services.

So in 2021, voters won’t need to wait until the May 18 primary election day to decide whether they want to re-elect or replace Larry Krasner as district attorney and Rebecca Rhynhart as city controller; they can vote at the end of March, or anytime during April, or in early May.

Election-streaming significantly reduces the value that committee people had previously been able to deliver during the “get out the vote (GOTV)” period—the time leading up to and including Election Day.

In past years, the most devoted committee people distributed campaign materials—brochures, leaflets, and doorknob-hangers—promoting party-endorsed candidates during the week and the weekend before Election Day. Then, on the day of the vote, they stood outside their polling places, greeting voters and handing out sample ballots that highlighted the names and ballot positions of endorsed candidates. GOTV activity on behalf of a party-favored candidate could make a critical difference, particularly in lesser-known, down-ballot races.

In the future, adhering to the traditional GOTV timetable will mean missing all the voters who had already voted by mail, as about half of them did citywide on November 3. In the Mt. Airy division where I serve as judge of elections, 484 of the 658 votes cast were vote-by-mail.

Despite Covid-related risks, some citizens chose to venture out of their homes this month to vote in the traditional way, out of a concern that mail-in ballots might be disqualified or uncounted. But in future elections, when anxiety about voter suppression is not a significant factor, how many people would actually prefer to travel to a church basement, a library, or a vacant storefront and wait in line to cast their votes at a machine on Election Day, when they could just mail in their ballots?

In the short-term future, in-person, Election Day voters will continue to be a factor, but only to a limited extent; any GOTV activity based on the traditional days-before-election model is likely to have much less of an impact as mail-in voting increases.

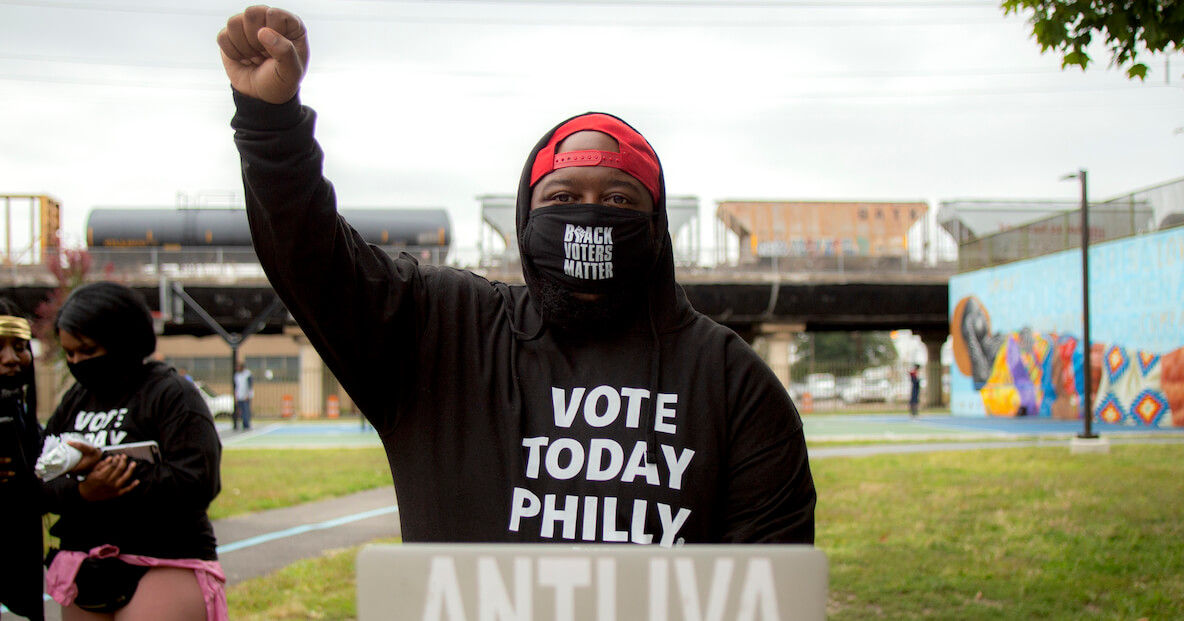

These changes pose new challenges for people who want to encourage increased voter participation in Philadelphia elections; but some of these people have found creative ways to do so.

Leading up to the June primary election, Nikil Saval’s campaign organized 500 volunteers who made thousands of phone calls to 1st District voters. Starting in August, Rebecca Poyourow and fellow activists in Roxborough’s 21st Ward launched a massive postcard- and letter-writing initiative to encourage residents to vote by mail for Joe Biden. They helped produce 3,700 more votes for Biden/Harris than the Clinton/Kaine campaign had received in 2016.

Although it will take years to fully recover from the crisis that has threatened democracy at the federal level, we can do a lot to reinvigorate democracy at the grassroots, and we can start now.

Some of the individuals who are most interested in increasing citizen engagement in Philadelphia elections happen to be Democratic committee people. Saval is one of them; Poyourow is another. But most committee people aren’t like them. Most committee people don’t know how to lead and manage a major voter engagement initiative, and many of them wouldn’t want to. More engaged voters means a greater likelihood that incumbent committee people could be challenged in the next election.

What to do? Get the names and addresses of the two committee people who represent the voting division where you live. One of those positions might be vacant, in which case you might have an opportunity to fill it. If not, then just reach out to the current committee people.

It won’t take long to find out if there’s a reasonable opportunity to work collaboratively with one or both of them to advance your interests in the upcoming 2021 primary election—your interest in learning how the DA and controller candidates would use their offices to help reform the Philadelphia Police Department; or your interest in educating voters about the best candidates for the judicial offices that will be on the May 2021 ballot (there will be more than a few of them).

If you don’t find an opportunity to collaborate with your current committee people, then consider doing what Chaka Fattah and other Black Power activists did during the late-20th century to disrupt the white-controlled City Committee infrastructure of that time: act as though you’ve already been elected committee person—not by fraudulently appropriating the title (which doesn’t carry that much authority these days anyway), but by doing all the things that the ideal committee person should be doing: helping newly eligible voters get registered, obtaining and circulating information about the next election, educating voters about mail-in ballots, and possibly organizing a (Zoom-facilitated) candidate forum, in coordination with a local civic group.

Learn the numbers of the ward and division where your polling place is located, then get a map of your division and make that division the target area for all your activities.

Ward and division geography actually makes sense. Because, by law, each division may not contain more than 1,200 registered voters, many divisions (there are nearly 1,700 of them) are walkable and compact. Like Saval, Poyourow, and the Black Power insurgent candidates, you can use this geography to your advantage, whether you have higher political ambitions or not.

You’ll have allies: Reclaim Philadelphia, Philadelphia Neighborhood Networks, the Committee of Seventy, and Philadelphia 3.0 all promote grassroots engagement in campaigns and elections in a variety of ways.

In the 2016 presidential election, nearly 400,000 Philadelphians failed to show up at the polls, and Donald Trump won Pennsylvania by 44,000 votes. Since then, more of us have gained a new appreciation of the need to defend the integrity of our democratic institutions. Although it will take years to fully recover from the crisis that has threatened democracy at the federal level, we can do a lot to reinvigorate democracy at the grassroots, and we can start now.

John Kromer, who served as Philadelphia housing director during the Rendell Administration, is the author of Philadelphia Battlefields: Disruptive Campaigns and Upset Elections in a Changing City.

Header photo by Phil Roeder / Flickr