For Cristina Laboy, who lived and worked in Kensington for 12 years, the signs of a potentially gentrifying neighborhood were unmistakable. The new architecture didn’t fit: Newly built homes with flat roofs were three stories tall instead of two. New residents weren’t taking public transit. There were more cars on the streets.

Originally from South Philly, Laboy moved north over 20 years ago and saw first-hand the effects of gentrification when she lived in Fishtown, the neighborhood next door. In Fishtown, housing prices and rents had skyrocketed (along with the number of espresso bars, biergartens, yoga apparel boutiques … )

“I always say to my husband, like, they are just rewriting the history of Philadelphia!” she says. “Because some of the areas that even he grew up in have drastically changed and it doesn’t even look like the neighborhood he came from.”

Despite its current reputation as the world’s largest open-air drug market, about a decade ago, below Kensington started attracting high-end real estate developers. They came for the convenient location, the accessible public transit, the parks, the classic multi-story brick buildings that make excellent lofts — and the inexpensive investment opportunities, especially South of Lehigh Ave.

They bought low. They sold high. Soon, rent and housing prices increased to the point that some longtime residents were getting priced out of their neighborhood. Then, they started eyeing opportunities North of Lehigh, and rents and land pricing started to increase there too.

Ten years on, the situation has changed. Rents are still high. But traditional residential developers have slowed their roll. Says Brian Murray, partner and CEO of Shift Capital, which, alongside community development corporations, has been working to bring sustainable growth to the Kensington Avenue corridor, “The opioid crisis has put the idea of investment above Lehigh Avenue at a standstill.”

“Drive or walk along Kensington Avenue and you will see vacant storefronts, businesses unfitting to the neighborhood, some serving as capital extraction tools for bad actors, and a smaller cluster of community businesses,” adds Murray. “Growing the cluster of businesses the community wants is an uphill battle.”

Today’s Kensington might be one of the most unlikely places in the country to start a nonprofit driven by residents and business owners who believe in their neighborhood, who want to be able to afford to stay and stay open there. But that’s exactly what Kensington Corridor Trust (KCT) is doing.

KCT has spent the last three years developing a purpose-driven land trust model that quite literally puts the control of development into the hands of the neighborhood, enabling residents and businesses along the Kensington Corridor to decide how the community evolves.

“KCT really has an opportunity to bridge these challenges,” says Murray. “With an affordable structure, a mission-oriented structure, a strong community presence built on trusted relationships and ownership, they’re able to tap into local businesses and attract value-aligned tenants that’s very exciting for the neighborhood.”

A neighborhood changes

In the 19th century, Kensington was a working-class hub dominated by small textile firms and tanneries. A third of Philadelphia’s textile companies and workers were located in Kensington. The Stetson Company had a factory here that employed 3,500 people making their world-famous hats. Armour and Swift operated slaughterhouses and meat-packing facilities into the 1950s.

But mid-20th century deindustrialization also happened here. Loss of manufacturing caused high unemployment, economic decline, population loss, and abandoned properties. The classic story of White flight, where middle class and wealthy White people relocated to the suburbs and poorer Black and Hispanic families moved in, played out as the city failed to invest in the neighborhood. Alongside poverty rose predatory businesses that flourished throughout the 80s and 90s. Drugs flowed into the area, and drug and gang-related crime followed.

Still, by 2015, Kensington began seeing the same revitalization that Fishtown had seen in previous years. New businesses came in as the old multi-story brick buildings turned into breweries and artist space. But ensuing residential development was not directed at the people already living in Kensington.

After the housing market recovered from the Great Recession, real estate development in Kensington was fueled by a drop in prices and inflated resale values. Luxury developments like Kensington Courts at Lehigh and Frankford, which broke ground on $369,000 homes in 2018, and real estate companies selling custom and remodeled homes in East Kensington for up to $800,000 have moved in. In September of this year, Viking Mill, which had been converted to artist studios and small business space 15 years ago, was sold to a developer for conversion into 178 luxury apartments.

The median income per person in Kensington’s zip code (19134) is under $18 000, less than half the already poverty-level median income for Philadelphia. Forty percent of residents live below the poverty line, double the rate in the region. According to KCT, before Covid, unemployment was at 24 percent, almost five times the city’s total unemployment rate. Despite being one of the poorest areas in the city, Kensington’s median rent in 2019 was $1,199, while the city median — which factors in the city’s richest and poorest neighborhoods — was $906

KCT is conceived

Laboy was not alone in recognizing the signs of gentrification. Four organizations doing work in the neighborhood were already dealing with it. Shift Capital, a registered B corp real estate development firm touting inclusive, equitable community development, opened the socially responsible apartment community J-Centrel in 2019. Community action organization Impact Services was focusing on jobs and homes, especially for those reentering society and building stronger connections between community members.

IF Lab’s The Idea Factory, located in J-Centrel, is a multi-use space offering programs, classes and workshops for minority entrepreneurs. PIDC, the public-private economic development corporation, had also been working on spurring economic growth in the neighborhood. In 2019, these organizations partnered to form Kensington Corridor Trust. Their goal: Create a way for the existing community to have control of new development.

Adriana Abizadeh is the executive director of KCT. “These partners looked at the state of the avenue, the blight, the challenges to small business, and then looked at real estate as a way to move the corridor forward and revitalize the community,” Abizadeh says.

There are several models for urban development: private developers (which tend to be the most wealth-driven and least equitable); Community Development Corporations, which address underserved areas through expanding affordable housing and other services; Community Land Trusts, which emphasize home ownership and also try to ensure affordable housing in a community; and Business Improvement Districts, which focus on stimulating the economy in commercial areas through business development.

“None of the existing models were designed to protect and preserve real estate in a way to benefit the neighborhood,” Abizadeh explains.

KCT put together something new: a Neighborhood Trust model. More than a land trust, it is a “perpetual purpose trust,” existing to advance a charitable purpose rather than having beneficiaries. While many urban development efforts serve the local community and use community engagement as a tool, KCT’s Neighborhood Trust ensures that the residents and business owners in the neighborhood maintain local control of property, including its “use and values,” while profit is reinvested in the community to improve quality of life.

As Abizadeh wrote in the KCT + Purpose: Transitioning into Community Stewardship report, “Utilizing collective ownership a neighborhood can quickly intercede when gentrification is looming; the power is placed back into the hands of residents and small business owners to decide the future of their neighborhood.”

While Philadelphia has plenty of land and garden trusts, a purpose-driven land trust for commercial use is unique. And as far as KCT can tell, there is only one other neighborhood trust in the US: in Kansas City, Missouri, with the same legal framework, a 501c3 formed around the same time as KCT called Trust Neighborhoods.

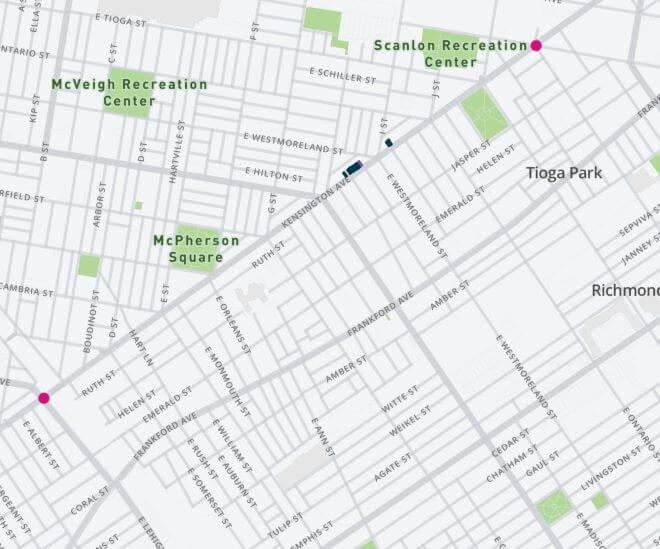

The geographic area of KCT is along Kensington Avenue from Lehigh to Glenwood. Residency for the purposes of the trust is defined as those in the 19134 zip code and the six census tracts along Kensington Avenue from Lehigh to Glenwood as well. KCT acquires properties by assuming debt, and also receives grants, primarily from foundations. By the fall of 2021, KCT had secured enough property and raised enough liquid assets to put the project in motion by creating a governing framework and defining the purpose of the trust, which would have to be achieved through broad community engagement.

KCT conducted outreach with businesses on the Kensington Corridor and nearby residents in Fairhill and East and West Kensington. A summary of the purpose trust proposal was provided in both English and Spanish. Residents and business owners said they wanted better jobs and career opportunities to entice people to stay in the neighborhood, more support for entrepreneurship, greater trust and connection between neighbors, reduction of crime and “drug tourism.” Transitioning the area to a mixed-income neighborhood would ideally trigger these improvements.

The process

Laboy, meanwhile, had decided to be a more active member of the community. That’s how she found herself at a Friends of McPherson meeting in early 2022 where KCT Community Organizer Jasmin Velez made the announcement that they were looking for individuals to serve on what sounded like a new kind of planning committee. “I guess I wasn’t paying attention,” Laboy laughs. “It wasn’t until shortly into that first meeting when I realized … It was more like strategic planning, it was almost like setting up bylaws. It was very interesting. And we were so engaged that two and a half hours later did not feel like two and a half hours later.”

Six Community Working Group sessions were conducted over the next six months. They would define the legal purpose for the Neighborhood Trust, outlining what outcomes the community wanted to see in development and economic investment. They would also define the governing structure and requirements to serve in that capacity.

“It was a really good group,” says Laboy. “We had community members, we had individuals who had businesses on the corridor, and there were other professionals from other agencies throughout Kensington. And quite a few block captains. It was such a diversity of individuals in this group and it was just amazing.”

The working group built the purpose and structure of the Neighborhood Trust by asking who “wins” when development changes the neighborhood. It has to be equitable, they concluded, and prioritize gains for those who live and work in Kensington. The governing structure of the Neighborhood Trust is reasonably simple. The Trust Stewardship Committee consists of nine members from the community (Kensington residents, community leaders, youth leaders, Kensington Avenue business owners, managers, or leaders, and one KCT Board member) who make the decisions in accordance with the purpose of the trust.

For example, a business that wants to open in a KCT-owned property would be evaluated by how it benefits the community. Is it going to provide jobs? What part will the business owners play besides running their business? Something as simple as a corner bar being replaced by a take-out beer distributor has lasting neighborhood consequences. Instead of a staff serving neighbors connecting in the establishment, people would congregate on the street where a cashier sells them alcohol. Covid exacerbated this problem, forcing many convenience stores and delis to close their entrances and deliver goods through take-out windows.

“They gave us all the tools and the equipment needed, and we were just putting them in place,” says Laboy. “It was broken down very easily so that it could be understood from all levels, so there was nothing super complicated. And if there was for someone, once they asked that question, it was broken down in a way that you knew the person understood. It showed me that they were very invested in making sure that individuals understood the process and understood each component that they were working on. You know, everything mattered to them. And so that was amazing for me, because I haven’t seen that passion in a project for so long.”

Laboy was present for the final presentation KCT put together for the public on August 31. “It was such a positive vibe in that room that it was just pure and sincere, what their mission was. And so I ended up nominating myself to serve on the committee.”

KCT currently controls 15 properties, including buildings and lots, along the Kensington Corridor. They already lease five mixed commercial/residential spaces. The collaboration between KCT and other nonprofits and CDCs (community development corporations) required to build the trust has continued, allowing KCT to acquire more affordable housing units from CDCs, arrange an agreement with the city to have trash picked up twice a week, keep green spaces clean, run home ownership programs and upkeep, and create a network of professionals who support real estate and business development for KCT and corridor businesses, connecting the community to ongoing workshops on real estate.

A proposal for a two-story building on what is currently a vacant lot at 3310 Kensington Avenue, their first new construction project, will include commercial space on the ground level and apartments above.

The mission going forward, according to KCT’s strategic plan for 2022-2024, is to “Utilize collective ownership to direct investments on the corridor that preserve culture and affordability while building neighborhood power and wealth in Kensington.” A big part of this movement is piloting a community investment program where individual residents can “buy-in” and invest in KCT.

The term for serving on the Stewardship Committee is two years. Laboy is looking forward to it, not just for the experience in her own community: “Say one of us moves out of that corridor and then does the same in another area, do you know what I mean? We could just reach out and grow and allow residents that live in these communities to have more say in what they want in their communities.”

The KCT Neighborhood Trust Stewardship Committee is accepting applications until October 31, 2022. The application is available in English and Spanish; other languages can be accommodated. Eligible community members can apply here.

![]() MORE COVERAGE OF COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE COVERAGE OF COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT FROM THE CITIZEN