Last March, as the Covid-19 lockdown got underway in Philadelphia, Cristina Martinez and Ben Miller of South Philly Barbacoa welcomed friend and fellow chef Aziza Young to use their kitchen at El Compadre to provide free meals for low-income and elderly Philadelphians. Collaborating with furloughed chefs, Young prepared 80 meals a day—and started a movement.

Martinez and Miller partnered with 215 People’s Alliance (215PA), a community organizing group, and—pulling from Young’s model—launched The People’s Kitchen. The rotating team makes 215 free meals per day while educating people about food justice issues in the city.

Because the stakes were so high, people thought up and implemented new ideas fast. Ideas that solved not only pandemic-caused problems, but also stubborn problems the pandemic only exacerbated—senior isolation, lack of support for small businesses, poor working conditions for restaurant staff, hunger.

Since late March 2020, The People’s Kitchen has provided over 60,000 free, chef-prepared meals, distributed through partnerships with nine community-based organizations in Latinx, Black, white, and Southeast Asian communities. Some 200 volunteers have supported the project and last summer, they partnered with Church of the Redeemer Baptist in Point Breeze to grow produce on a section of their land.

And the project is still going strong. Every week, The People’s Kitchen employs 20 to 30 diverse chefs, restaurant workers, student apprentices, and emerging community leaders (thus far, they’ve provided 12,000 hours of paid-employment and educational opportunities) At the end of this month they’ll launch their second growing season with 50 plots at Church of the Redeemer.

Initiatives like these have been among the brightest spots in the nightmare of this pandemic in which there has been so much darkness—starting with the more than 3,000 Philadelphians who have lost their lives to Covid-19 in the last year.

Because the stakes were so high, people thought up and implemented new ideas fast. Ideas that solved not only pandemic-caused problems, but also stubborn problems the pandemic only exacerbated—senior isolation, lack of support for small businesses, poor working conditions for restaurant staff, hunger.

Which is why, of the 13 groups we checked in with (below), all but two—which ran projects directly addressing Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) shortages—plan to continue their initiatives in some form post-pandemic. And after hearing from them about their impact, it’s hard not to be in awe of Philadelphians’ ability to dream up holistic, status-quo changing solutions (too bad our politicians can’t do the same).

“I’m really excited about the leadership that has grown from the kitchen, and different projects that have come through this creative food-centered movement,” says Carly Pourzand, 215PA member and The People’s Kitchen’s project coordinator.

The People’s Kitchen has partnered with the Coalition for Restaurant Safety & Health and is co-facilitating worker committees, like the the Comité de Trabajadorxs (Latinx Worker Committee), a group of immigrant workers focused on building a restaurant industry that is is safe and positive for all workers, including those who are undocumented, and both back of house and front of house staff. “We have been in the ‘back of house’ helping restaurants for years,” they wrote in a statement. “Now it’s time to try our food and hear our stories.”

As for the original concept, “We plan to continue this free restaurant model as long as food insecurity is a problem in the city, and as long as we can find funding for it,” says Pourzand.

They just launched their sustainer campaign—if 1,000 people donate $25 per month, they could continue providing more than 1,500 meals to hungry Philadelphians every week and power their work to address the root issues of food insecurity.

What’s remarkable is just how many stories there are like this in Philadelphia. See for yourself what stellar citizens of our city have done (and are doing) to get us through the pandemic and beyond.

Project Shields

Last March, Penn alums Tiffany Yau, Michael Wong, Evan Weinstein and John Gamba set up at Pennovation Works, recruited volunteers and started 3-D printing face shields 24/7.

From spring to fall, Project SHIELDS distributed more than 150,000 reusable face shields to frontline workers in Philly and beyond. Workers could safely disinfect the shields and reuse them, plus they helped preserve the longevity of their face masks.

They slowed down their production last fall, as the supply of PPE caught up with demand. The team has returned to their social entrepreneurs roles—leveraging cleantech to create safer public spaces and providing social entrepreneurship education to marginalized communities.

Yau and Wong say one of their highlights was being able to safely bring together members of the Philly community to volunteer a few hours of their time. “It really felt like we were able to create a sense of hope and community during a time where that seemed close to impossible.”

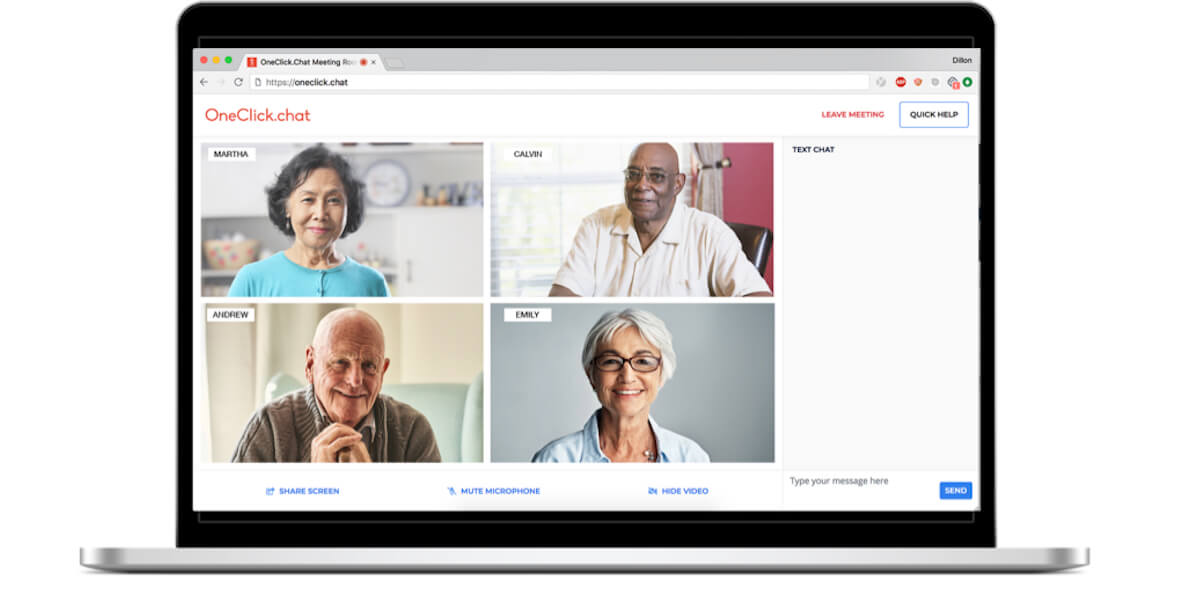

OneClick.Chat

For more than four years, OneClick.Chat’s user-friendly platform has made it easier for older adults to connect via video chat. And in the past year, unsurprisingly, the platform’s total usage grew by more than 400 percent.

During the pandemic, the Philly-based company—founded by Alan Gibson and Dillon Myers—partnered with nursing homes across the country to host daily free virtual events like social mixers, yoga classes, music concerts, and interactive museum tours, which have helped about 4,000 attendees from across the country feel more connected.

“I am a senior with underlying medical conditions which make me vulnerable to Covid. I haven’t left my house since last March—one year. I am so grateful for OneClick. I feel part of a community, which I never would have had the opportunity to do staying home,” said one user.

Loneliness was considered a public health crisis before the pandemic, and it will only be worse after—OneClick.Chat plans to continue hosting free, daily events, says co-founder Dillon Myers. This summer they’ll be part of a clinical trial to measure how participation in their events affects health and quality of life outcomes.

“As many of us have experienced, social interaction can be the difference in someone’s day—whether it’s a neighborly check-in, a call with an old friend, or a conversation with a friendly stranger,” says Myers. “It doesn’t have to be in-person to be meaningful.”

Pennsylvania 30 Day Fund

Back in April, many mom and pop businesses without the resources to apply for PPP loans were in dire straits. To their rescue, a group of baller civic leaders (including the magnanimous Jeffs—Bartos and Brown), who launched the Pennsylvania 30 Day Fund to get money into the hands of as many small business owners as possible—easily and quickly.

To date the group of eight local business leaders have raised over $3.3 million, providing $3,000 forgivable loans to more than 1,000 small businesses across all 67 Pennsylvania counties; 59 percent of the funded businesses are woman-owned and 49 percent are minority-owned. Only one percent of surveyed businesses have closed permanently since receiving their loan.

As their one-year anniversary approaches, it’s clear that small business owners across the state are going to need support for years after the pandemic. So the Fund is working to evolve into a sustainable organization that will provide tailored resources to businesses, and opportunities for business owners to come together (live and virtually), share ideas, learn new skills and ultimately strengthen their businesses and wider communities.

Proyecto Tamal

From April 2020 to March 2021, Proyecto Tamal raised more than $80,000 for 70 furloughed Latinx cooks who weren’t able to access unemployment or other government benefits. These cooks shared their own food traditions and recipes, which were incorporated into the menu each week. Through the course of the project, they crafted 44 different tamale-focused menus (many sold out in mere hours) highlighting cuisines from across Mexico, Central and South America.

The tamales, made with fresh masa from local corn, were so popular, they expanded production and brought on three Latina cooks (who were past participants) to work full-time.

“A big lesson in starting and running this project is that when you have a community of people who want to support an idea, you can get things done really fast,” founder and chef Ana Caballero says. Last week, she announced: “With the critical months of the pandemic behind us, we are closing this chapter of our work and taking a breather.”

But it’s not over. Caballero plans to host pop ups and farm dinners this summer and fall as she figures out next steps.

Collective Success Network

When college campuses made the decision to evacuate last March, many—especially first generation college students—didn’t have the ability to comply with the universities’ demands that they clear out of their dorms at once. Here in Philly, the Collective Success Network (CSN), a non-profit that supports first generation low-income college students, stepped up.

CSN raised more than $18,000 and allocated $1,000 in donations for their chapters at Drexel, Temple and Penn. Students spent it on gift cards for supplies, rent for a storage unit for 22 students to store their dorm room belongings, and transportation. They also distributed 127 $50 grants to help students defray the cost of transportation, groceries, cleaning supplies, and other emergency needs. Through their laptop drive, they disbursed 25 computers.

While their Covid-19 relief program wound down last fall, “The needs of [first generation low-income] college students continue to be great since their family members are often amongst those hardest hit by the pandemic,” says CSN director Nancy Li.

With a grant from the Eagles Social Justice Fund of the Philadelphia Foundation, they’re planning to expand support to students at smaller colleges and universities in the area, by organizing an intercollegiate “consortium” chapter starting this fall.

Mask Match

Swarthmore alums Emma Ferguson and Colin Schimmelfing brought their tech skills to MaskMatch.com, helping to redistribute PPE to folks who needed it most.

In the first six months of the pandemic, Mask Match—with the help of 300 volunteers—distributed 950,000 masks from 7,300 donors to frontline workers.

They wrapped up the project last August. “We never planned Mask Match as a forever thing,” says Ferguson. “We always intended to get as many masks as we could, as fast as we could, out of everyone’s toolboxes and closets and into the hands of healthcare workers.”

When they started receiving larger donations that their systems weren’t optimized for, they redirected their donation pages to GetUsPPE, an organization they’d been in touch with, that’s still going strong. (“Lots of mask donation organizations were communicating via one giant Slack workspace!” says Ferguson.)

“There were a lot of shifting community needs in the U.S. between March and July of 2020,” says Ferguson. “By focusing on just one thing our core group agreed was extremely important—peer-to-peer mask donation—we were able to get really, really efficient at that one thing.”

Bread Drop

In the early days of the pandemic, soup kitchens across the city shut down and folks experiencing homelessness had fewer opportunities to get food. In response, Hatfield resident Lou Farrell started Welcome Bread in partnership with The Welcome Church of Philadelphia to get filling meals—primary peanut butter and jelly sandwiches—to people in need.

Welcome Bread—now called Bread Drop and part of the E-Meal program at Emmanuel Lutheran Church—operates with the help of 70 volunteers (many who make sandwiches in their homes), 17 partner churches and three food pantries to distribute sandwiches across three counties. Last month, they served up their 100,000th PB&J, and they now distribute fruit and snack bags, too.

The concept is being adopted in Ridley Park, Lansdale and Cherry Hill, where volunteers have developed their own production and distribution networks based on the Bread Drop model.

As volunteers stay engaged and the project gets continued support from community members, Farrell doesn’t plan on wrapping it up any time soon. “It’s not that complicated,” says Farell. “People can really wrap their minds around it because they can do good work in their homes.”

Aardvark Mobile Health

Throughout the pandemic, infrastructure has arguably been the most important piece of the Covid-19 testing and vaccination puzzle. Which is why a Conshohocken-based mobile events company turned their trucks into mobile testing facilities, which have been deployed in multiple states.

Here in Philly, Aardvark Mobile Health partnered with vybe urgent care to administer 175 to 200 tests per day in their mobile clinic. With three of their vehicles, the City is bringing testing—and vaccinations once they become more readily available—to sites like adult centers, assisted living facilities and community centers.

Aardvark’s trucks are easily sterilized, air conditioned and heated, and are equipped with a generator so they have long-term functionality. They can be used to, say, provide physicals at schools in under-resourced communities or free dental cleaning for veterans.

“When the pandemic first hit, we really weren’t sure if we’d be able to continue operating, since our business prior to Covid-19 was driven primarily by events-based experiential marketing,” says founder Larry Borden. “We’re extremely proud that we were able to pivot during a difficult time for many businesses to create and manufacture purpose-driven mobile health vehicles that are custom-built for Covid-19 and beyond.”

Piseitta Arrington

The day after Community College of Philadelphia shut down on March 18, staff member Piseitta Arrington set up a temporary food pantry outside her Fox Chase home. Holding up a sign that read simply, “Free Food” she urged passersby to stop and get what they needed.

Now, through her organization SisTerhood for Women in Motion, she feeds about 100 families each month. And she distributes food to two organizations in Chester, feeding 300 to 500 families each month.

During the pandemic, Arrington got a grant through Governor Wolf’s Food Recovery Infrastructure Grant Program to purchase a refrigerator and deep freezer, allowing her to store perishables and expand her offerings. As her food pantry grows, she has no plans to stop. She’s hoping to find donated space where she can store clothes and other essentials, along with non-perishables.

“Families will always need food,” she says. “No one should be hungry.”

New Kensington Community Development Corporation

The New Kensington Community Development Corporation provided rental assistance to more than 130 Philadelphians in 2020—with funding from PHDC Shallow Rent Pilot Program, NeighborWorks America, Wells Fargo, state, city and private donors. Through Philadelphia’s Eviction Diversion Program, they also helped 51 clients secure agreements with their landlord (and are in negotiations with many others).

Folks in retail, health care, and the restaurant industry make up the majority of the tenants NKCDC has counseled; most are six months or more behind.

“We try to cover one month’s rent up to $1,000. It lessens the delinquency to the point where we can figure out an affordable payment program with their landlord,” says Joe Filipski, associate director of Housing Services for NKCDC. “Renters can remain in their homes until they’re financially stable. It basically stems the tide of homelessness.

More than half the city’s renters—19,000 Philadelphians—faced eviction in 2019, even before the pandemic. And with more financially vulnerable people, NKCDC’s work will be needed long after the pandemic.

“Evictions harm everyone,” said Dr. Bill McKinney, executive director at NKCDC. “They harm families, landlords, neighborhoods, taxpayers, and the city we all live in. These strategic interventions are averting an even worse crisis, but we also need funding and attention for policy and legislative solutions. Half of the city’s renters facing eviction in 2019 is not a baseline anyone should aspire to.”

Mask On! Philly

Last spring, before we forgot what the bottom half of faces look like, Leon Caldwell and business partner Melissa Lamarre of Community Transformation Partners set out to get homemade cloth masks to Philadelphians without them. They provided the fully stocked workspace and invited volunteer and aspiring sewers to join the effort.

From May to September, Mask On! Philly distributed more than 1,000 masks and face shields to organizations like the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium; partnered with the Philadelphia Department of Public Health to create and distribute 2,000+ postcards with Covid-19 prevention and mask use/care tips; and taught 30 community members how to sew. They also spent $1,000 in fabric purchases at local businesses.

“It is a difficult task to manage a volunteer-based program with a small budget,” says Lamarre “But it was definitely worth it to know that masks did circulate to our most vulnerable community members, and to see the faces of volunteers when they successfully finished sewing a mask.”

She and Caldwell hope to re-launch the program and make PPE like gowns and caps to teach volunteers advanced sewing skills. For now, they are seeking new philanthropic partners to support community training and health safety efforts. (If you’re interested in donating or providing a workroom/ facility, email ctpcdc@gmail.com.)

Together We Can

The challenges of getting food to people who need it are often logistical—literally connecting available food to those who are hungry. In Delaware County, Patty Bassett launched Together We Can (TWC) to match families in need directly with donor families by making use of existing delivery services like Instacart and Roadie.com.

Since last May, TWC has raised close to $75,000 and provided fresh groceries totaling over 20,000 meals. Their administrative costs are covered by separate private donors—meaning all community contributions are used to support families facing food insecurity.

Bassett plans to continue long after the pandemic, keeping her focus on three critical food insecurity factors: quantity, variety and nutrition. Her first goal for 2021 is to raise at least $75,000 to cover the cost of delivering groceries for high-risk families.

“Food insecurity has existed in this country long before the Covid-19 pandemic—the crisis has greatly exacerbated this fundamental problem,” says Bassett. “Together We Can plans to work as long as it is needed to tackle food insecurity until it can eventually be eradicated.”