Aside from two high-profile upsets in 2019, Philadelphia City Council has been a very low-turnover local legislature for all of modern history, with councilmembers serving exorbitantly long terms.

Almost purely generational turnover has introduced some newer members into the body over the last two election cycles, mostly through the at-large seats, but what you rarely see happen is serious challengers running and winning in district seats—the real power seats on Council.

Max Marin’s excellent 2019 piece for WHYY, “How Fear Helps Philly Politicians Stay in Power,” looks at some of the reasons why it’s so extraordinarily hard to unseat a district councilmember:

But as the single mother sets out to court donors, she’s run into a problem. People are terrified to give her money because of who she’s running against.

Even the act of trying to raise money has built-in resistance, she discovered. Convincing a local venue to rent her space for a fundraiser was a struggle, she said, because the business owner worried about political retribution.

When you run against an incumbent, no one wants to support you. I had one elected legislator laugh in my face.

In a city where a single political party is as dominant as the Democratic Party, to have essentially no competition in primary elections is a sign of civic sickness, and it’s no wonder there’s been such an observable disconnect, especially recently, between what the public wants, and how city government operates.

Making matters worse, Philadelphia is the only big city in the U.S. that has mayoral term limits but no City Council term limits, setting up an important structural political disadvantage for the office of the mayor. Either both offices should have term limits or neither should, but the current scenario is arguably the worst possible one, allowing the governing body most attuned to parochial special interests to accrue seniority and power, often at the expense of the citywide interest that is the mayor’s prerogative.

The 2019 election cycle was an unusually competitive City Council cycle, and 2023 seems likely to be even more so, given the likely cascade of retirements from councilmembers who’ll need to resign in order to run for mayor. There could be as many as three at-large seats opening up, and the rumor mill is also replete with talk of prospective district challenges too.

In a city where a single political party is as dominant as the Democratic Party, to have essentially no competition in primary elections is a sign of civic sickness.

But two cycles of unusually high competitiveness do not necessarily make a trend, and elected officials should do more legislatively to force some regular turnover on City Council if it isn’t going to happen organically.

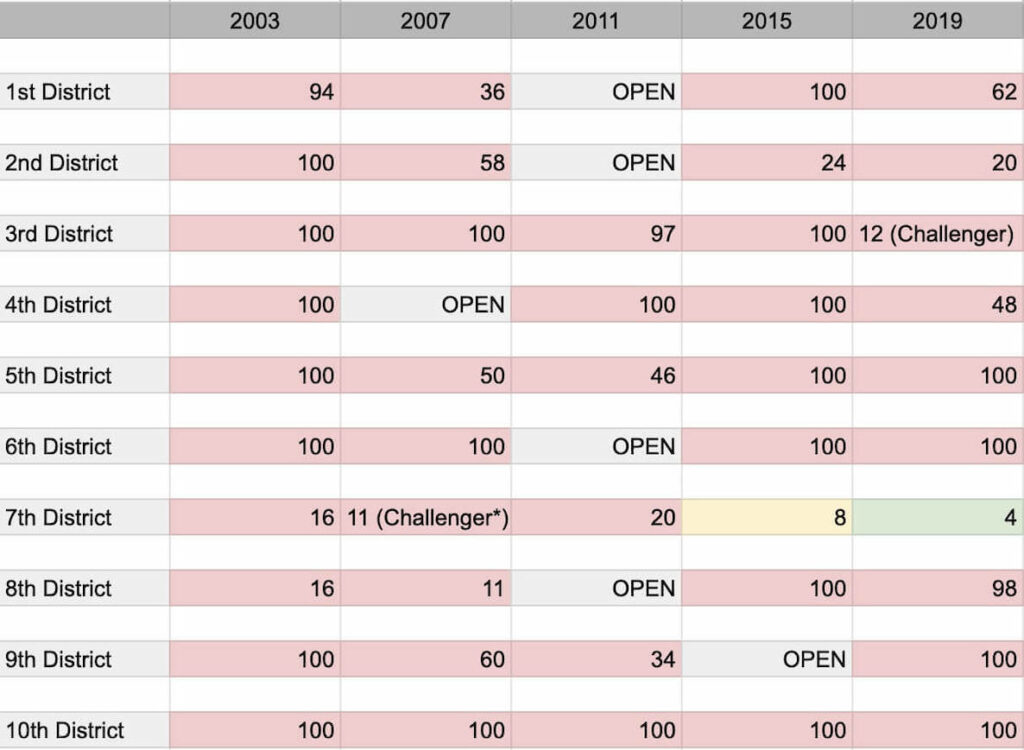

Just to get a sense of how rare competitive elections are in District Council races, we put together a table overviewing the point differential in the 50 primary races over the last five election cycles.

The red cells are races where the incumbent won by more than 10 points, which is a rough cut-off for a race being even relatively close. Nearly every race is in red, and in most of these races, the incumbent won by over 90 points.

There are some exceptions. In 2007, 7th District councilmember Maria Quiñones-Sánchez beat Danny Savage by 11 points. Savage took over the seat via a special election only six months before the race, replacing Rick Mariano, so he didn’t get to benefit from the full incumbency advantage. The party continued to back challengers to Sánchez in 2011, 2015 and 2019, which explains the truly tight outcomes and why the 7th District is so anomalous.

Additionally, in 2019, challenger Jamie Gauthier beat 27-year incumbent councilmember Jannie Blackwell. This race was the first time since 1991, when Michael Nutter beat Anne Land, that a challenger beat a full-term district incumbent.

Sanchez’s win in 2007 and Gauthier’s win in 2019 represent the only times a challenger has beaten a district incumbent of any kind in a generation.

There were also six open seats during this span. Three of them were the result of the incumbent councilmembers, Anna Verna, Joan Krajewski and Marian Tasco, resigning from office in their late 70s or early 80s. Then-councilmember Michael Nutter resigned to run for mayor. Two incumbents decided not to run again for more political reasons: 8th District councilmember Donna Reed Miller and 1st District councilmember Frank DiCicco.

Voters almost never have the opportunity to hold their district members accountable in the ballot box because there are so rarely credible challengers. And there are rarely any challengers, because district councilmembers keep siphoning power from the mayor’s office, making going against them an increasingly risky proposition. As a result, there is almost never turnover, and when there is, it is almost entirely due to a generational changing-of-the-guard.

That’s why it’s encouraging to see Councilmember Allan Domb’s new charter change proposal that would establish a limit of four four-year terms for City Councilmembers picking up steam.

The bill has six supporters already—Allan Domb, Helen Gym, Jamie Gauthier, Mark Squilla, Derek Green, and Kendra Brooks—though it needs 12 to make it onto the ballot. That supporter list with members from across the political spectrum represents a potentially fascinating strange-bedfellows coalition that holds out some hope this could actually happen.

What other issues do Helen Gym and Allan Domb ever usually agree on?

The four-term limit—while admittedly a bit excessive for term-limits purists, especially given the mayor’s continued two-term limit in this scenario—should be an acceptable compromise as it would still allow for a very long term of service of 16 years, while also creating a predictable schedule of turnover that would create more openings for new leaders to run.

Voters almost never have the opportunity to hold their district members accountable in the ballot box because there are so rarely credible challengers.

It would also adequately address the main objection to term limits, which is that they advantage lobbyists and special interests by inhibiting the formation of institutional and policy knowledge in the legislature.

While a one-term limit could certainly be said to create such a problem, that just isn’t true of a 16-year term. The change would still allow for councilmembers to make long careers in government, while creating some predictable, guaranteed open races that future candidates could plan around if they didn’t want to challenge sitting members head-on.

This, along with Councilmember Derek Green’s public financing bill, and the exploration by Councilmember Isaiah Thomas’s office into ballot order randomization, could all help to promote a more competitive and accountable government in Philadelphia.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

![]()

MORE ON PHILADELPHIA CITY COUNCIL

Header photo by Jared Piper / Philadelphia City Council