Christine Rouse, founder of Acting Without Boundaries, may very well have been born with the acting bug. “My parents said I was a natural born actress,” she says.

But having also been born with cerebral palsy, sharing her dramatic talents onstage proved impossible. Rouse, of Haverford (and a distant relative of Philadelphia developer Williard Rouse), says when she was a teen, she would frequently audition for lead roles at her Catholic high school on the Main Line. But she never received them. “High school was difficult. I felt isolated and never felt like I belonged,” the now-48-year-old says.

But those lonely years of high school had an upside. They motivated Rouse to advocate for other people, especially kids, with disabilities. At age 16, she created Kids Are Kids (now called Melodie’s Program), to do disability awareness outreach to children and adults.

An advocate is born

“I wanted to educate kids at a young age about differences. Kids are more receptive when they are young and don’t have prejudices,” Rouse says.

Kids Are Kids began as a one-day program Rousse put on at the summer camp her brothers founded. “It was so successful that teachers from local schools called and started booking me for presentations at their schools,” Rouse recalls. With the support of family, and a network of volunteers, Rouse took Kids Are Kids on the road, presenting to schools, colleges, and other organizations.

Today, she says, “We teach people about differences and one’s ability despite one’s disabilities. We do sensitivity activities such as trying to button a shirt with socks on their hands to [experience] what it’s like if your hands didn’t work right. Because I have cerebral palsy, it is hard to button, and eating can be difficult. We [also] bring wheelchairs, walkers, and blindfolds so people can experience what that is like.”

“People with disabilities are still fighting to be given the same dignity and opportunity as their abled counterparts. AWB allowed me to find my voice in that fight, and encouraged me to follow my dreams,” says Hannah Brannau.

Rouse’s aim is not only to educate but also to celebrate the various ways people live with disabilities. “What makes us different, makes us beautiful,” she says. Between 2004 and today, the program has visited more than 200 venues, from Greater Philadelphia to Connecticut, Maryland, New York and even Florida.

After founding Kids Are Kids, Rouse earned her degree in elementary education from Saint Joseph’s University. But she never forgot her first love, acting. A few years later, Rouse went away to a two-week theater workshop for adults with physical disabilities. It would prove to be a life-changing experience.

“I loved it!” she says. “I met people [with disabilities] from all over the world. I took classes in theater, music, and dance. At the end, we did a short performance of monologues and songs for family and friends.”

She had finally found a space where the right training and accommodations allowed her to release the actress within. A star was born.

An advocate for actors

But Rouse wanted to do more than advance her own career, and the theater workshop gave Rouse another idea: Create an acting program for teens and young adults with physical disabilities.

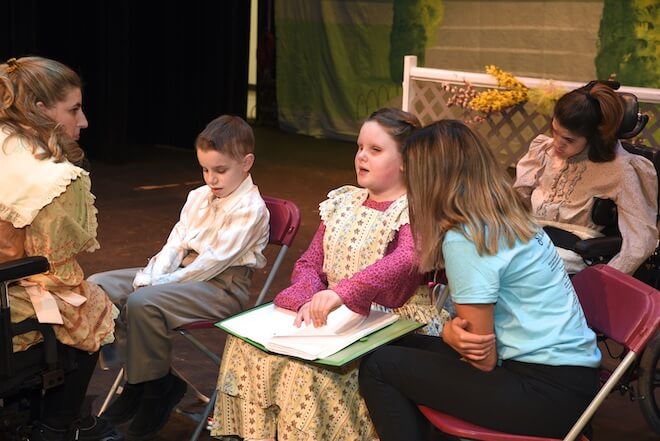

That program became Acting Without Boundaries (AWB), a year-round Philadelphia-area theater company with a mission to “provide disabled [actors] the opportunity to pursue their love of acting and performing while building their belief in themselves and their abilities.”

Rouse founded AWB in 2004. The Bryn Mawr-based organization serves actors between the ages of 5 and 30. There are two requirements for participation: 1. Have a physical disability, and 2. Have the capacity to memorize lines. Generous private funding allows AWB to offer their programs free of charge.

“Our actors have a variety of disabilities, including cerebral palsy, blindness and visual impairments, hearing impairments, actors who are nonverbal, and [those with] traumatic brain injuries.” Consequently, the accommodations AWB provides are as varied as their participants’ disabilities.

“We provide scripts in large print and Braille, rehearsal and performance spaces are accessible to people who use wheelchairs and walkers, and audio description during our performances for audience members who are blind or visually impaired. Some actors who are nonverbal use an assistant to record their lines on an iPad. During a show, the actor activates the line by pressing a button on the screen. Other actors who are nonverbal use a touchscreen communication device called a Dynavox to voice their lines,” Rouse explains.

Actors learn a host of techniques, such as delivery, staging and character development. Rouse, who still takes private lessons from AWB’s artistic director Neill Hartley, says actors also receive training in directing and scene writing. There is a space for every actor in a production. “Some [AWB participants] prefer to help behind the scenes as assistant directors, dramaturges, or narrators. Everyone works on active listening and communication skills and growing in their self-confidence and creativity,” Rouse says.

AWB’s senior program for actors in their mid-teens and older meets monthly. Their season culminates with a fall performance. This year, AWB partnered with the Philadelphia Artists Collective (PAC) to present The Contrast at the Seaport Museum. Twenty actors, including two from PAC, performed in the play, written in 1787 and believed to be the first comedy brought to the stage written by an American citizen. The Contrast was the group’s eighteenth performance to date. Previous productions include Anything Goes, Meet Me in St. Louis, Mary Poppins, Singin’ in the Rain, Annie, Grease, The Little Prince, Peter Pan and The Sound of Music.

The junior program for actors aged five through early teens meets monthly for nine months and performs in the spring. The junior group is invited into the process of writing the script and lyrics. Their spring performance of Philadelphia writer Jimmy Curran’s children’s book, Will The One-Winged Eagle, is scheduled for May 21, 2023.

Philadelphia actors without boundaries

Evan Linden lives in Center City, joined AWB in 2017, and had dabbled in acting for years prior. Born with cerebral palsy, Linden began fully using a wheelchair just three years ago and has also been diagnosed with borderline personality and obsessive-compulsive disorder, which, they say, “is a huge part of my life.”

Linden’s cerebral palsy is visible, but their conditions aren’t, and they were open with AWB about their mental health as well as their identification as non-binary. A few years ago, Linden told Hartley they were more comfortable playing male roles. In The Contrast, Linden was cast as the villain, Mr. Billy Dimple.

Rouse’s aim is not only to educate but also to celebrate the various ways people live with disabilities. “What makes us different, makes us beautiful,” she says.

There is a marked difference between working with mainstream theater companies and AWB, Linden says. “With AWB it felt less about the disability and more about: We want you here because we know you can perform.”

What’s more, AWD “is an outlet and elevates my mood,” Linden says. They’re also proud of the group’s advocacy work for people with mental illness. “There is a stigma associated with people with borderline personality. My job as an advocate is to show that the assumption that we are all bad is completely not true. We are up there performing; we have the capabilities.”

Damon Bonetti, cofounder of PAC, says partnering with AWB fits his organization’s twofold mission of presenting rare classical theater and working with companies that may not otherwise perform these off-the-beaten-path pieces.

“We want those voices to be heard,” Bonetti says. PAC has also collaborated with the bilingual troupe, Teatro del Sol; all-Black theater company, Theatre In the X; Philadelphia Asian Performing Artists; and Theatre Ariel, which performs plays that speak to the Jewish experience.

With these partnerships, PAC primarily serves as the production entity, leaving the collaborative group with full artistic reign. AWB did, however, request two PAC actors, handpicked by Hartley. PAC’s belief that all actors’ work has value isn’t just for show: They paid stipends to the AWB actors, as they do with all their partner actors.

Hannah Brannau joined AWB at its inception in 2004. Brannau, who has cerebral palsy, recently played Laura Wingfield in the Arden Theatre’s production of Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie.

“AWB should be recognized for the incredible talent and friendships that it fosters. People with disabilities are still fighting to be given the same dignity and opportunity as their abled counterparts. AWB allowed me to find my voice in that fight, and encouraged me to follow my dreams. I’m so proud of every single actor in AWB and so grateful for their friendship and support!” she says.

The troupe has grown steadily over its 31-year history, from about a dozen actors in 2004 to 27 active actors today, serving 60 actors in all. Similarly, staff and volunteer support has expanded, from originally Rouse and three part-time helpers, to Rouse, five part-timers, and a small band of dedicated volunteers for each production, plus a larger pool of volunteers, some from local colleges, who support AWB as needed.

The City of Philadelphia reports over 16 percent of Philadelphians have some type of disability. If any of those folks have the acting itch, there is a place ready to receive them.

“As new actors join, we do all we can to provide the accommodations they require,” Rouse says.

![]() MORE STORIES ON THE ARTS FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE STORIES ON THE ARTS FROM THE CITIZEN