It has been just over 25 years since the publication of In Black and White: Race and Sports in America. Books age rapidly. The question I asked then, set out in the preface, was, “what can we do about the underrepresentation of African Americans in the top-level positions in sports management?” I sought to answer the question utilizing the-then nascent Critical Race Theory framework. Little did I know that the obscure legal theory would, a quarter of a century later, become highly controversial and, not coincidentally, misunderstood.

The foundational question of my book 25 years ago still drives much of my writing and thinking today, in my position as CEO of the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University. Much in the book remains relevant today, though the reader is advised to replace my 25-year-old Rodney King references with George Floyd, insert Colin Kaepernick as the historic stand-in figure for John Carlos and Tommie Smith, and substitute some of the sports power position holders I interviewed then with the leaders of today. Sadly, almost uniformly, not much else has changed.

RELATED: NFL players should do more than just protest—like take a real stand for change

When I wrote the book, there were three African-American head coaches in the 30-team NFL. Today, that number is still three—in an expanded 32-team league. There were three African-American managers in Major League Baseball, and today there are only two. Not all of the numbers are bad. The NBA had five Black head coaches in 1996, versus 13 in this upcoming season. But clearly, the NBA has been an outlier. The fact is, too little has changed in the last 25 years.

Eliminating racism is about the taking of steps that only a person in power can take.

At one point in In Black and White, I attempt to set out how difficult it is to bring about impactful change on racial equity by putting rules or laws in place. I write, referencing what is known as “cargo culture,” that “In the 1962 movie Mondo Cane, New Guinean Aborigines built an airstrip, hoping to attract the planes that frequently pass overhead. They hoped to change the behavior of something they had no control over by putting all of the elements in place for the desired result—the landing of an aircraft.”

This “if you build it they will come” cargo culture framing was long before the emergence of Field of Dreams in 1989. Today, I see that type of aspirational hopefulness as actually the heart of the problem. We keep building systems, rules, devices and even laws to address racial inequities, particularly in hiring, and we make little or no progress. This failure to find a path to address the true controlling problem is what is at the heart of Critical Race Theory.

RELATED: Wanna take on systemic racism? One word: Infrastructure.

In the early 1990s, Critical Race Theory was both young and rarely mentioned in reference to sport. My colleague and sometimes co-author Professor Timothy Davis had begun some work to do just that in his landmark 1995 law review article “The Myth of the Superspade: The Persistence of Racism in Collegiate Athletics.” What is the connection between Critical Race Theory and sports? That is what I both overtly and indirectly set forth to outline 25 years ago. I specifically referenced:

Three key themes from the critical race theory literature. The first, incorporated throughout, is the view of the impact of color-blindness and the failure of such policies in addressing existing race problems. Racial inequalities cannot be resolved unless race is, in fact, taken into account. Second, an important element in amplifying this need to eliminate color-blind theories for resolving discrimination is the existence of unconscious racism. To move forward in solving our problems, we must recognize that unconscious racism exists in all of us. Finally, this book also embraces Derrick Bell’s concept of the permanence of racism in America.

From there my analysis began. Unconscious racism may be the one item in that trilogy that I hesitate to hold fast to today. That is, there are times where if you assert racism is unconscious, an alibi is actually being provided for a racist act. It becomes an excuse for an act that may have been part of one’s consciousness—who is to know?

With even greater clarity today, the principles of CRT explain why there is so little progress in the elevation of Blacks and other people of color. I’ve reeled back some on my embrace of unconscious racism; I think 25 years later it’s hard to not confront your own racial beliefs when making hiring decisions. Beyond that hesitancy, I also go back and forth on limiting my analysis to Blacks and Whites as well as the lack of any discussion of intersectionality, a huge flaw.

I wrote the book almost five years after Kimberle Crenshaw’s article in The University of Chicago Law Forum titled “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics” alerted us all to the importance of recognizing the uniqueness of, for example, Black women in any analysis. Their plight is not properly covered by only looking at Blacks or only looking at women.

There are times where if you assert racism is unconscious, an alibi is actually being provided for a racist act. It becomes an excuse for an act that may have been part of one’s consciousness—who is to know?

In the book, I assert the uniqueness of African Americans and our arrival in the United States via slavery as opposed to immigration. That is certainly the basis for a unique analysis. But still the analysis of other people of color is absent. The absence of the analysis of women is only mildly justified as the focus of the book is largely on professional team sports in an era where there was no longstanding women’s team sports league such as the WNBA. But, the book was about diversity in leadership positions and there did not need to be a women’s league for women to be in the leadership mix.

Today, as then, I’d analogize that building of the airstrip with the law and I’d extend that to well-intentioned attempts like the Rooney and Selig rules. Those are the rules in place for the NFL and MLB respectively to increase the number of diverse leaders in power positions hired by requiring that diverse candidates are part of the hiring pool. What we’ve learned is that teams can be mandated to interview one or two “minority” candidates and then will still go ahead and hire a white man.

In the final chapter of the book I highlight the long term, three-step approach to bringing about change: (1) acknowledging the existence of racism and discrimination, (2) the usage of affirmative action to break this down over time, and, finally, (3) achieving the goal of multiculturalism. I say that we could be stuck in that second phase for a while…I alluded to forever, but I’m not sure then if I thought forever was as long as 25 years.

RELATED: How the Sixers can save the city

In the Supreme Court’s Grutter v. Bollinger 2003 case, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote in her majority opinion that “race-conscious admissions policies must be limited in time,” adding that the “Court expects that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.” We are fast closing in on that 2028 date.

One principle of Critical Race Theory that I would spend more time on in my analysis today is “interest convergence.” It was raised most assertively by Derrick Bell in his classic 1980 Harvard Law Review article, “Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest Convergence Dilemma.” The principal is simple and meshes psychology, economics and public policy. For example, if city planners simply sought to fund curb cut-outs for disabled individuals, the policy has only the narrow support of the disabled and their allies.

But interests converge when it is highlighted that bicyclists can more easily maneuver from sidewalk to street, walkers are less likely to trip and drainage away from homes may be assisted. As leadership has become more diverse, it has become popular to recognize “the business case for diversity and inclusion.” There exist now major studies focused on the concept that a diverse workforce improves an entity’s bottom line, because of the diversity of ideas this variety necessarily brings.

I’m convinced the answer is not one of building the airstrip. It is finding those paths of interest convergence such as the business case for diversity, equity and inclusion in sport.

In the end, where I was most wrong was in searching for rules as a remedy to racism. Twenty five years ago, I wrote about the piling on of laws and rules and an inordinate amount of special programs for Black candidates, something the White candidate does not have to endure. In the book, I posited a composite Black candidate asking, “Why should I have to go through some special training program when my white counterparts have moved in and out of the system for so long without such programs?”

Now I’m convinced the answer is not one of building the airstrip. It is changing the hearts and minds of those making the decisions. Of those taking action. Finding those paths of interest convergence such as the business case for diversity, equity and inclusion in sport. That means understanding what’s in it for those you are asking to take the affirmative action. Eliminating racism is about the taking of steps that only a person in power can take.

That is the answer to my question of 25 years ago: “What can we do about the underrepresentation of African Americans in the top-level positions in sports management?” If interest convergence is the answer, how do we make that come about? If there’s one thing that’s become clear over the last quarter century—in sports as well as society—it’s that if we’re going to end decisions in hiring that are influenced by racism, overt or otherwise, we’re going to have to do more than pass laws and adopt rules. We’re going to have to change hearts and minds.

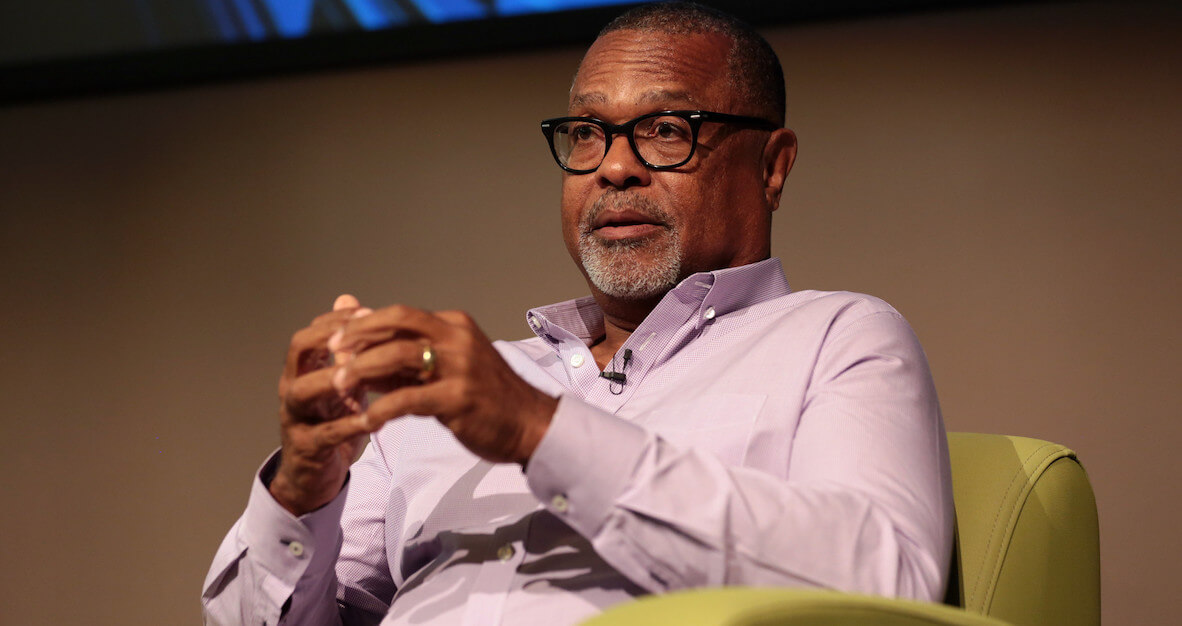

Kenneth L. Shropshire is the CEO of the Global Sport Institute and the Adidas Distinguished Professor of Global Sport at Arizona State University and the David W. Hauck professor emeritus, Wharton School. He is the author of many books, including Sport Matters: Leadership, Power and the Quest for Respect in Sports and In Black and White: Sports and Race in America. He splits his time between Philadelphia and Scottsdale, Arizona.

![]()

MORE ON SPORTS AND GOOD CITIZENSHIP

Kenneth L. Shropshire, CEO of the Global Sport Institute | Photo by Gage Skidmore / Flickr