Inquirer reporters Jake Blumgart and Sean Walsh talked to outgoing Council President Darrell Clarke about one of the big themes of his tenure in office, which I also wrote about a couple weeks ago: the steady power shift from the Mayor toward District City Councilmembers on land use and built-environment questions.

Clarke announced Feb. 23 that he is not seeking reelection, ending a 40-year career in City Hall, which includes almost a quarter-century on City Council, 12 of those years as the Council’s leader. The defining principle of Clarke’s tenure — empowering hyperlocal decision-making, often at the expense of citywide policy — could last long after he is gone.

It can be seen in the ever greater latitude of district Council members to set rules specific to their territory — to the chagrin of those who argue that it creates a patchwork of rules that makes it harder to do everything from making streets safer to opening a new coffee shop. It also tends to privilege the loudest voices, which are usually those most opposed to change.

This was also one of the themes of Philly 3.0’s City Council questionnaire, which I’ve been referencing to discuss some of the policy stakes of the 2023 elections. To try and understand candidates’ political orientation on the land use issue, we asked them two questions:

Last year, the City adopted new regulations for streeteries that empowered each District Councilmember to decide whether outdoor dining in their district would be allowable by-right or subject to a discretionary process. This resulted in a mix of the two approaches across the city. As a general matter, should business regulations such as this be decided at the citywide or district level?

And:

As a general matter, when in the development process should community members/organizations and District Councilpeople exert influence over land use and building permits: Front-loaded via comprehensive neighborhood-wide planning, or at-the-moment on a project-by-project basis?

What’s the context?

The goal with these questions was to try to get a gut check from candidates about where they stand on the politics of governance.

Do they tend to prefer citywide, predictable rules for everyone, with public engagement and planning happening at the front end of the process? Or do they tend to think there should be more scope for discretion for the District Councilmembers and near neighbors to make decisions on a project-by-project basis?

The Inquirer piece on CP Clarke’s leadership on these issues does a good job of describing how the Council President has been an extremely effective advocate for the latter approach, steadily shifting the governing dynamic over built-environment issues toward the 10 District Councilmembers.

Clarke’s critics argue that his approach to policy-making harms small business and undermines larger affordability goals. They contend that giving Council members near-complete control over land-use decisions in their districts — a practice that Clarke has encouraged — opens the door to corruption.

They point to the profusion of zoning carve-outs for particular neighborhoods (known as overlays) under Clarke’s guidance, discouraging density on key commercial corridors, and erecting barriers to new shops or the convoluted rules entangling outdoor dining that shut down most streeteries […]”

Nutter’s zoning code reform effort, meanwhile, has been undermined by a series of overlays that changed the rules in parts or all of Council members’ districts. The increasing complexity has created a lot of work for land-use lawyers and slowed the Zoning Board of Adjustment to a crawl, frustrating everyone from shopkeepers to big developers.

The combined effect of CP Clarke’s efforts has been to turn housing politics into a mostly within-district issue, empowering the types of organized interest groups that are influential within Council Districts, and taking the At-Large Councilmembers — nominally elected to represent the whole city — almost completely out of the conversation on a major city issue with clear citywide and regional economic implications.

Why does it matter?

Walsh and Blumgart point out that it wasn’t too long ago that there was major citywide policy action on housing, beginning under the Street administration with the Philadelphia 2035 Comprehensive Plan, and then continuing with the voter-approved Zoning Code Commission updates to the city’s zoning code from 2007-2012. The Comprehensive Plan update and various agency initiatives put the Nutter administration’s stamp on a number of citywide housing issues, but under the Kenney administration, it became much less clear what the Mayor’s housing agenda was.

Depending on the Council district, the process for opening a daycare, legalizing an existing AirBnB, putting a cafe table and chairs outside of a restaurant, or building a simple rowhouse could be substantially different from the process just a few blocks away.

Citywide housing policy action on anything dealing with land use issues has become very rare. Throughout Mayor Kenney’s two terms, the Planning Commission became a much quieter service department, rather than one of the principal voices in citywide debates over housing the way it has sometimes been in the past. In the tug-of-war between the Mayoral administration and City Council leadership for power over the built-environment, it’s often seemed that only one side was pulling on the rope at all.

Instead, Mayor Kenney seemed content to let the Council President drive almost the entire agenda on every major housing issue with little pushback. As Dan Pearson pointed out in an Inquirer editorial last week, some of Clarke’s housing initiatives like the Neighborhood Preservation Initiative and Turn the Key cost as much as some major Mayoral administration priorities, but received substantially less debate or media scrutiny.

What is the outcome we want?

In 2024, the pendulum should swing back in the direction of a much more engaged and policy-agenda-driven Mayor and At-Large City Council faction who want to be more assertive about legislating in the citywide interest.

Philadelphia’s broad housing market outcomes are far too important to everyone’s material well-being and the city’s economy to be left up to parcel-by-parcel politicking over every building, and having clear rules with ministerial approval is the best path to success.

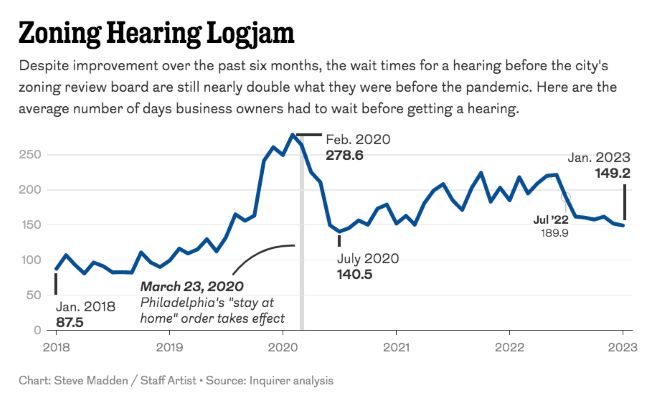

I’ve written on numerous occasions about how Councilmembers try to push more housing projects toward the zoning variance process, which is more politically charged, and last week Jake Blumgart and Ryan Briggs published a story about the increasingly slow process for small businesses to get zoning variance hearings too.

Business owners large and small have been stymied by wait times that averaged six months in 2022 before a case could be heard by the city’s Zoning Board of Adjustment (ZBA), which considers exceptions to the zoning rules that dictate what can be built in the city […]

Since the pandemic, case delays have worsened even as the City has added staff and funding to the board.

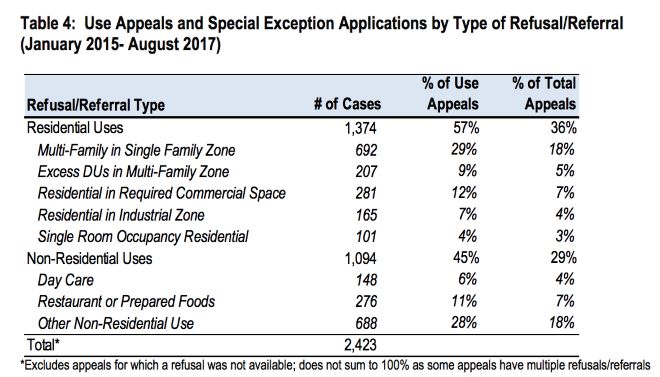

The situation is especially acute for small-business owners. In many parts of the city, zoning rules make it difficult to open any commercial enterprises. To make matters worse, City Council continues to place additional restrictions called overlays on specific neighborhoods or commercial corridors. Originally designed to discourage what neighborhood groups saw as a nuisance, they often force businesses as anodyne as ice cream parlors to receive a zoning variance to open.

At a time when the city is struggling to regain lost jobs after the pandemic, the slow pace of approval for people who are already trying to open businesses should be viewed by the Mayor as an emergency priority. The Zoning Board of Adjustment isn’t hearing record numbers of cases — the current case totals are in line with past volumes — but the hearings are taking longer because the Kenney administration isn’t managing the time.

Unfortunately, the situation doesn’t seem to have tempered any City Councilmembers’ enthusiasm for passing even more bills that could be predicted to clog up the ZBA calendar.

Mayoral candidate Rebecca Rhynhart was the only candidate so far to comment on the issue, although her reaction doesn’t quite touch on the core issues — there are still too many variance cases, and the hearings are taking more time because of Zoom and poor time-management.

We cannot continue to allow our slow zoning process to limit business growth.

As Mayor, I will appoint a senior official to identify and reduce the interdepartmental issues that prevent many small businesses from getting started and growing. https://t.co/HlgEMRDAU4

— Rebecca Rhynhart (@RebeccaRhynhart) March 5, 2023

More agency coordination and a clearer roadmap of the necessary department approvals would certainly help, but the fundamental problem is that too many common types of businesses and buildings have to go through the zoning variance process, which is supposed to be reserved for exceptional cases.

Over the last two terms, some City Council District members have methodically funneled more and more workaday activities into the zoning variance process, which is inherently more political and discretionary. Depending on the Council district, the process for opening a daycare, legalizing an existing AirBnB, putting a cafe table and chairs outside of a restaurant, or building a simple rowhouse could be substantially different from the process just a few blocks away.

The Planning Commission’s 5-year Review of the city’s zoning overhaul, published in 2017, also found that City Council’s changes to the code have tended to work against what land “wants” to be, creating more variance pressure.

For example, one of the more common types of changes Councilmembers would make is rezoning from RM-1 (small apartment buildings) to RSA-5 (rowhouses.) But then among the most common types of variance cases involve people trying to convert rowhouses and townhouses to small apartment buildings. Remapping all residentially-zoned land to RM-1 would be one very effective way to wipe out much of the caseload at the ZBA, but City Council has been going in the opposite direction.

The bottom line is that getting the variance cases through the ZBA faster would be helpful, but the 2023 candidates should keep their eyes on the prize: right-sizing the rules and applying them citywide so fewer cases have to go before the ZBA at all.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

![]() MORE FROM JON GEETING ON WHAT’S AT STAKE IN OUR NEXT ELECTION

MORE FROM JON GEETING ON WHAT’S AT STAKE IN OUR NEXT ELECTION