I had never been to a boxing gym until 2015 when I was invited to contribute photographs by Art on Avenue of the States Gallery in Chester (now ART504) for a fundraising event for the Pennsylvania Regional Golden Gloves at Must Fight gym in Chester. The Golden Gloves boxing tournaments take place in a large number of states around the United States and culminate in the National Golden Gloves tournament.

When I googled boxing gyms in Philadelphia, I discovered that the James Shuler Memorial Boxing Gym in West Philadelphia was only a 15 minute drive from my house in Wynnewood. Some people are surprised to hear that I just drove into a neighborhood not always safe for outsiders and walked into the gym. Actually, boxing gyms are safe havens for anyone with an interest in the sport.

When I arrived, the gym’s owner, Percy “Buster” Custus was sitting outside with some friends. He quickly decided I had a legitimate reason for being there and gave me a quick tour of the place. I had permission to take photographs.

Buster told me he had named the gym after his friend, middleweight James “Black Gold” Shuler. They had trained together at Joe Frazier’s gym. When James was just beginning to reach the top of the pro rankings, he was hit by a truck as he rode a new motorcycle home from the shop.

As I walked around the gym, I was greeted with a friendly welcome from the first few people I met, which put me at ease.

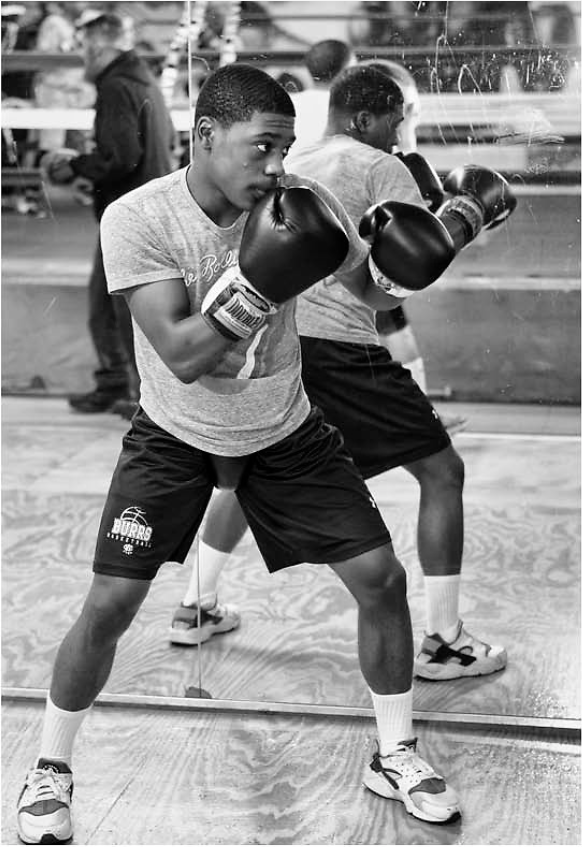

James Shuler’s brother, Darryl Shuler, was at the gym to pick up his sons, who were training. He kept me spellbound with stories about James and gave me my first lesson about the value of boxing. None of Darryl’s kids were ever in trouble and “were never handcuffed.” He said, “Boxing keeps kids out of trouble.” It teaches them defense and discipline. Father figures here teach them respect for their opponent and their neighbor so they only use boxing for self-defense. “In Black culture, the more activities you have, the less killing or hurting others you have.” While kids are at the gym, there is no chance for them to get into trouble.

After taking the photos I needed for the fundraiser, I became more and more drawn into the intensity of how the boxers were training and the intimate interpersonal interactions I witnessed. I began to document the people of this gym and what they were practicing and decided to make this book.

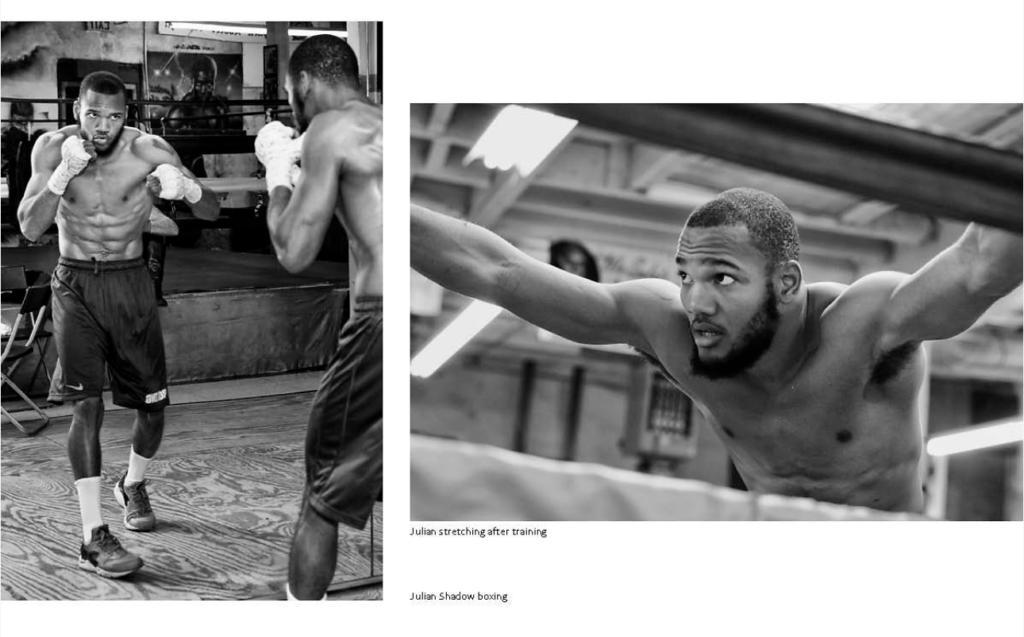

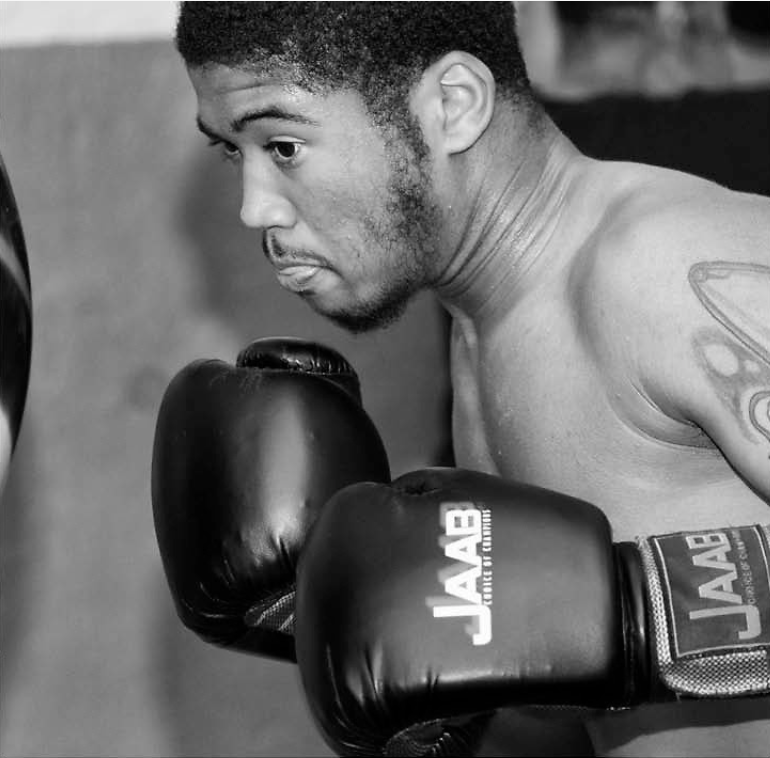

Not having been a boxing fan in the past, I have become fascinated by the sport and the community of people so deeply immersed in it. This sport has a rich beauty to it on several levels. Boxing movements are surprisingly graceful, rhythmic and exciting to watch. As I am a retired dancer, this appeals to me. The training is complex and interesting. The skills achieved are impressive. The physique developed by boxers is pure sculpture. Previously I had focused most of my work as a photographer on dance, including a dance project in Rwanda, and on urban landscapes. Trying to capture boxing, which happens at a high speed in low lighting, was a challenge that kept me going back to the gym over and over again to try to capture what I was seeing.

This book aims to bring you inside this unique gym to meet the extraordinary people who have come through here and allow you to catch a glimpse of what they do. The photographs represent my personal connections to the people and how I feel about them. There isn’t a speck of objectivity here. Occasionally the photographs show the fighters the way they want to be seen, but I tried as often as possible to portray them as I see them. They are complex and beautiful human beings practicing a sport that is treacherous yet inspiring.

The boxers, trainers, referees, judges and doctors have taught me what I know about boxing, but my understanding of the sport is only as an observer. While certain people have been quite open with me and happy to talk about themselves on a certain level, this is a community with strong relationships and cultural styles of communicating that do not include me. I am a witness and I see things through my own lens, literally and figuratively.

Shar’ron “Aunt Coach” Baker

Shar’ron, was the first female boxing coach to work in Philadelphia. She is an expert on fitness and trains boxers on her own, but she also coached as a team with Naazim Richardson. She has started to win awards for her coaching, but women in boxing rarely get the same recognition for their achievements that men do. She feels she had a “good 10 year run with Steve Cunningham, Jamaal Davis, Dynamite and some others,” and now she is making a good salary as a coach on the 2020 Olympic boxing team.

She told me that fighters won’t believe a woman can train them at first, but she works them hard, and then they realize their mistake. When Shar’ron trains a fighter, they become part of her family and she watches out for them, even after they stop boxing. When Jamaal Davis moved away, she still tried to advise him about his career. She always waits for fighters who leave to come back. “I keep the porch light on.”

Khalil Stafford

Khalil Stafford took pride in training all four of his sons. Coaches take the training of family members very seriously. They believe that the harder they train them, the safer they can be in the ring. Khalil Stafford has a special talent for training children. He himself boxed only briefly.

When he stopped boxing, he bought a jewelry store in North Philadelphia and made some money for a time. His partner got arrested for beating up his girlfriend’s husband, and was deported because he was an undocumented immigrant. Khalil couldn’t make the business work on his own. He used boxing workouts to lose a tremendous amount of weight, and then came to Shuler’s gym to train boxers.

His 18-year-old son Khalil (Bump) and his 29-year-old grandson, also named Khalil, were both shot and killed in 2021. His son’s death was a terrible shock but his grandson had been living a dangerous life. Since their deaths, he says the only time he feels alive is at the gym. At home he is barely coping.

Allison Robertson

Allison Robertson (Alli) is a slender, White, young woman and a medical editor for exams and patient safety. She isn’t a typical member of this gym. I asked her why she boxes. “I like to hit people.” Her coach Sam Davis has her work out with the guys, but they aren’t allowed to hit her back. Allison Robertson did some boxing in college but only fought once. When she ended up with two black eyes, she decided to box just to improve her fitness. Sam says she has a lot of skill. He puts her through the same training regimen he does the male fighters.

Deandre Hudson

Deandre Hudson is a long-term member of the gym and close friends with Rasheen Brown. He won the state championship in his weight class at the 2019 PA State Golden Gloves tournament. He subsequently got caught drug dealing, but managed to avoid going to jail.

Khalil Stafford (Bump)

When Bump sparred, everyone stopped to watch. He was wild and fearless. After high school he joined the army and was doing well. His father, the older Khalil Stafford was very proud. When his girlfriend got pregnant, he left the army and moved back to Philadelphia. During the Covid pandemic he beat up a man who was attacking a young woman. The man came back with a gun and shot him. His death was a terrible shock. He was only 18 years old.

Coach Hamza Muhammad’s son put on boxing gloves and went running and tumbling around the ring. He stopped just long enough to see what I was doing with the camera, then went back to his antics. Parents bring children to the gym when they are very young to have fun and start to learn the rules of boxing.

This is an excerpt from Grace & Grit: Boxing at Shuler’s Gym by Jane Cohen. Copyright 2024 by the author and reprinted by permission of the author. Purchase the book here.

![]() MORE LITERATURE FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE LITERATURE FROM THE CITIZEN