to this story in CitizenCastListen

She was, among other things, a poet, a journalist, a civil rights activist, a teacher, a survivor of intimate partner violence. She was also a Philadelphian: Born in New Orleans in 1875, she spent much of her adult life in Delaware before moving here in 1932, and dying here three years later.

Now, her life is the subject of a fascinating online exhibit curated by The Rosenbach, and the inspiration behind Thaw, a ballet debuting this week as part of BalletX Beyond, a new online subscription service from the contemporary dance company co-founded in Philly in 2005 by dancers Christine Cox and Matthew Neenan.

The collaboration between BalletX and The Rosenbach comes at a time when, as The New York Times pronounced on January 13, “the arts are in crisis”: Professional creative artists, the piece reported “are facing unemployment at rates well above the national average—more than […] 55 percent of dancers were out of work in the third quarter of the year, […] when the national unemployment rate was 8.5 percent.”

That there was a synergy between BalletX and The Rosenbach (which works in partnership with Free Library of Philadelphia and, for this exhibit, with the University of Delaware) is the public’s gain: People from anywhere in the world can now log on to learn about Dunbar-Nelson through The Rosenbach’s free online exhibition, and experience the balletic interpretation of her work, specifically her poem “Sonnet,” with the premiere of Thaw on Wednesday, January 20, at 7pm.

Maintaining connections

When the pandemic hit Philadelphia last spring and arts venues throughout the city were forced to shut down, Cox was committed to keeping her staff employed, and her dancers dancing; no one on the team has been laid off.

“Even when we didn’t have any real sense of how or what we were going to do, we just kept working and checking in,” she says. And so BalletX continued to hold ballet class and workout fitness classes, albeit via Zoom.

“Humans crave connection. And when we work together in a community, when we honor and respect and support each other, we just get better and better,” she says.

While keeping staff and dancers motivated, Cox got to work creating the online platform as a vehicle to showcase filmed versions of original BalletX performances.

“There are definitely traditionalists who want the live experience, and I understand and value that completely,” she says. “But there was no way I was going to wait for us to get back to the normal, because the end [of restrictions] seems to be pushed out further and further,” she says.

Who was Alice Dunbar-Nelson?LEARN MORE

A $30-per-month “plus plan” includes all of that as well as access to a monthly rotating schedule of four ballets from the BalletX archive, and ticket discounts for future live performances in 2021.

Since it launched in September, 711 people have subscribed, 60 percent of them for the basic plan. Virtual subscription revenue is currently 45 percent of the earned revenue from the company’s regular performance series last year at this time; but even in a typical year, revenue from season performances is only roughly 15 percent of the company’s annual budget.

“Humans crave connection. And when we work together in a community, when we honor and respect and support each other, we just get better and better,” Cox says.

“Neither live performances nor BalletX Beyond are enough on their own to sustain the organization, but both are critical sources of revenue,” explains Josh Olmstead, of the company’s PR and marketing department. So while the company continues to be sustained largely from donations, it’s an encouraging model, particularly given that, as The Times piece said, “Beyond value in its own right, culture is also an industry sector accounting for more than 4.5 percent of this country’s gross domestic product.”

Alexander L. Ames, collections engagement manager at The Rosenbach, worked on the team that quickly transitioned from preparing an in-person exhibition about Dunbar-Nelson to an online one, and he credits the partnership with BalletX for amplifying his team’s work. “I was terribly worried when we began our work on the virtual exhibition about the question of Can we translate our content into the digital realm? And I think in no small part because of the BalletX collaboration, the answer is a resounding yes.”

Dance with a message

Thaw was choreographed by Francesca Harper. Cox had introduced Harper to the life and work of Dunbar-Nelson, and Harper felt an instant connection. Her father was a civil rights lawyer, and as a Black woman who grew up in largely white spaces, Dunbar-Nelson’s activism immediately struck a chord with her.

“My husband is Jewish and my daughter is biracial, and [Dunbar-Nelson’s work] put a lens on how I was feeling during quarantine and during the Black Lives Matter movement, and my own thoughts around race communication,” she says.

In particular, Harper was moved by the 1992 poem “Sonnet.” [Editor’s note: Dunbar-Nelson is often referred to with the inclusion of her earlier married name, Moore, as she is here.]

An excerpt reads:

I had forgot wide fields; and clear brown streams;

The perfect loveliness that God has made,—

Wild violets shy and Heaven-mounting dreams.

And now—unwittingly, you’ve made me dream

Of violets, and my soul’s forgotten gleam.

BalletX BeyondJoin

Harper invited her dancers to read “Sonnet,” then write and share what it made them feel; those writings ultimately helped drive the direction of the piece.

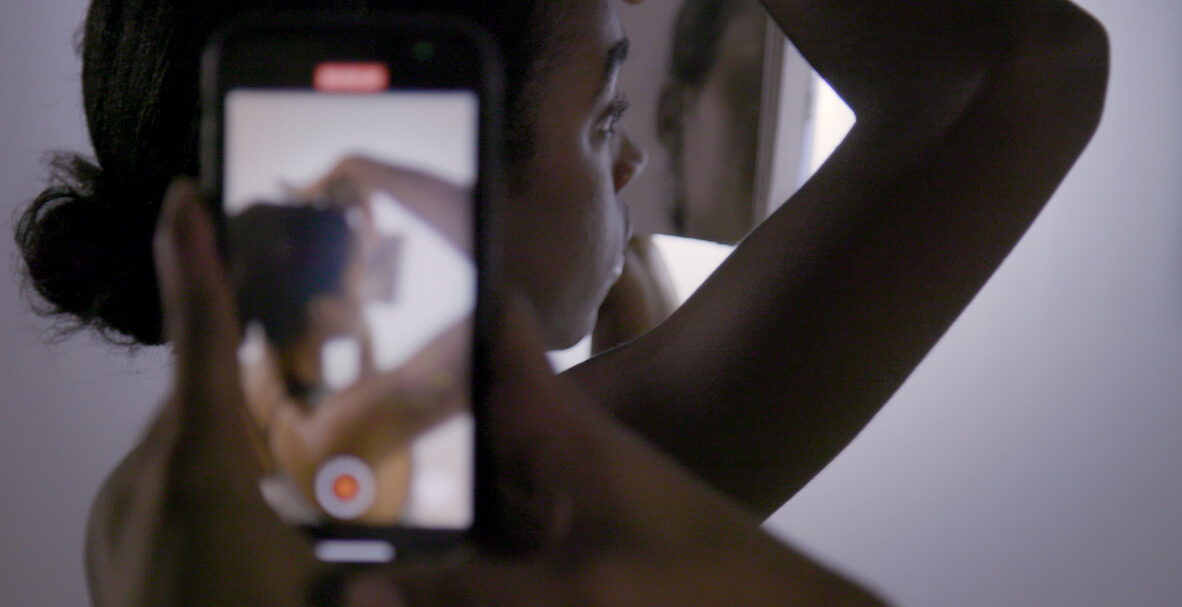

Dancer Ashley Simpson, whose powerful duet with fellow dancer Blake Krapels concludes Thaw, had just arrived in Philadelphia for her role in the company when the pandemic hit. She relished the chance to focus on dance, in some ways as a meditative practice, as the chaos of the world ensued, and she was particularly grateful for Harper’s collaborative process and her use of intriguing props: ropes made of light, boxes with mirrors.

Alice Dunbar Nelson was a survivor. She lived through difficult times, terrible circumstances, and made her mark on history in an indelible way,” says Ames.

“It was like a surreal dance environment full of endless possibilities,” Simpson says of rehearsals.

For safety purposes, dancers rehearsed with masks; leading up to the filming, they were all tested for Covid-19, and then they quarantined accordingly.

Thaw TeaserWatch

The Rosenbach exhibit will also continue to live online. And one can only hope that Dunbar-Nelson’s legacy and example do too:

“Alice Dunbar-Nelson was a survivor. She lived through difficult times, terrible circumstances, and made her mark on history in an indelible way,” says Ames, of The Rosenbach. “And I think that is a lesson for us today. She survived, thrived, and made a difference through challenging times—and we can do the same.”

Ashley Simpson in Francesca Harper's Thaw, showing week on BalletX Beyond | Photo by Daniel Madoff