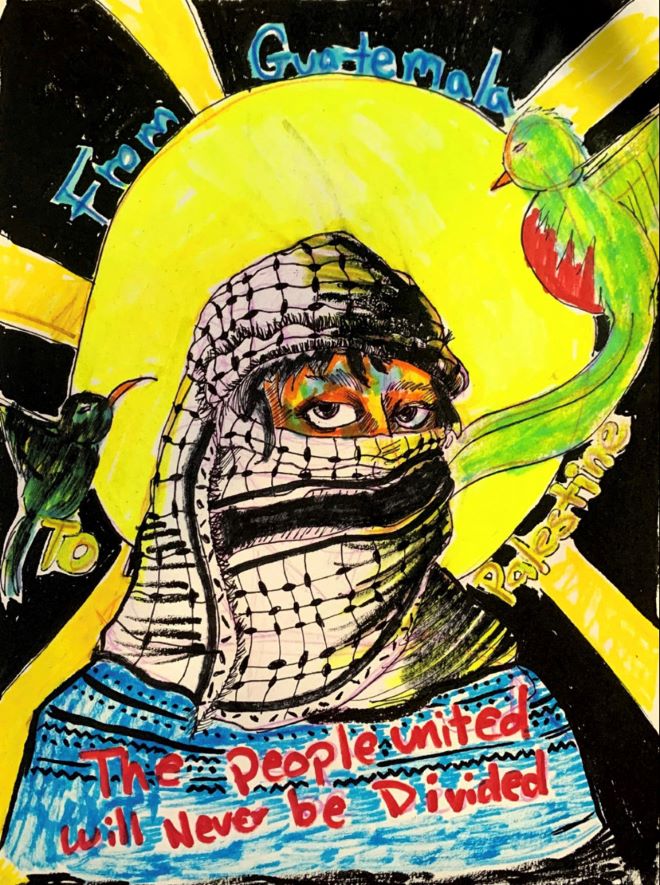

Chela Ixcopal possesses a creative and sensitive spirit, and he’s not afraid to use it. As a visual storyteller, Ixcopal centers queer, immigrant and Indigenous communities in his work. Ixcopal believes in being adamant for change. As he puts it, “Bully your politicians into what they’re supposed to be doing.” His creative efforts can be found in many forms: drawings, posters, fliers, protest signs and social media graphics, to name a few. His pieces often feature handwriting; his expressive lines create portraits and slogans that contain a visible quality of humanity.

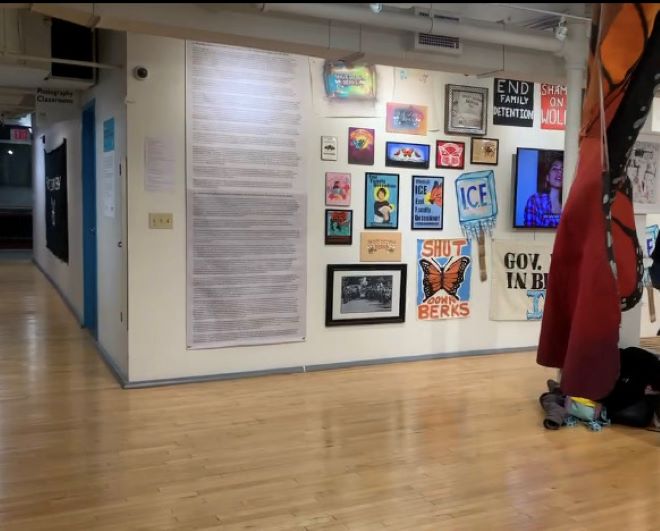

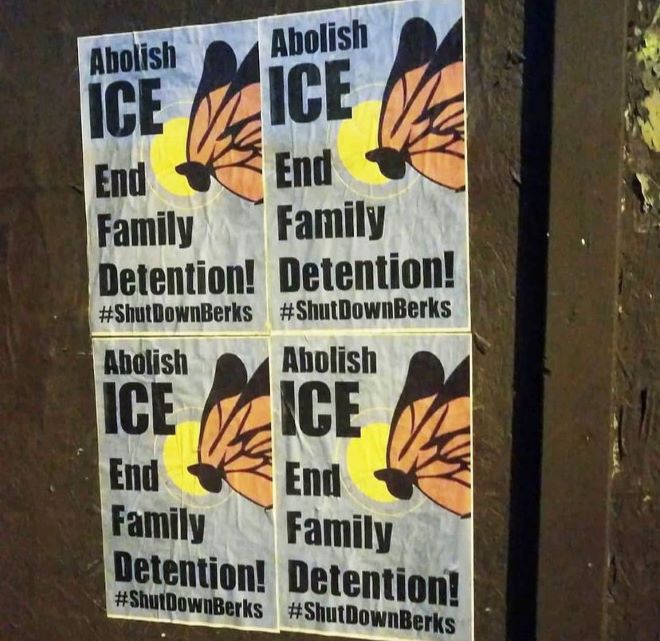

Last year Ixcopal received an Art and Change grant from Leeway Foundation to fund the artist’s work with the End Medical Deportation Campaign. In 2018, Ixcopal began working with the Shut Down Berks Coalition and now is part of a traveling exhibition, Queremos Justicia: How We Shut Down Berks. The exhibition tells the formative story of how the Coalition worked to close a Berks County immigration prison. Queremos Justicia: How We Shut Down Berks is slated to return to the Philadelphia area this July.

The road to being an artist has not been an easy one, and Ixcopal is quick to give thanks to friends and community members in Philadelphia who supported him on his journey. “I have been blessed to be able to find myself and to be able to create again,” Ixcopal says, “and to be able to be part of a community that’s so rich in different cultures.” He hopes to offer the same loving support to the young students that he works with as a teaching artist.

As part of a partnership with Forman Arts Initiative, the Citizen caught up with Ixcopal. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

RJ Rushmore: Who are some of the artists who most inspire you?

Chela Ixcopal: Usually, my friends are the people that I am really inspired by because they work with the same community that I also work with. José Lemus is one, I met him through mutual organizing. He’s really involved with Puentes de Salud [a volunteer-run health clinic for Latinx immigrants], which I was also involved in. He’s a beautiful, great artist and is very tuned into Indigenous art in Mexico. My other friend, Manny Vasquez, who works at Juntos [a Latinx human rights org], is a beautiful photographer. He does a lot of Indigenous dancing. There is Valentín Sánchez-Stoddard. They’re half Central American, and I’m also half Central American, so it’s really nice to see that inspiration in their artwork.

When did you become aware of how visual art can function in a political space?

It was actually at Moore [College of Art & Design], when I was studying Illustration there. During the Trump era of 2016, we were supposed to think about what we wanted to present for our senior thesis. I was so angry at that time and I really wanted to share the story of immigration rights. My father was deported when I was 12 years old, in 2006, and that really impacted me a lot. I really dug deep into interviewing my parents about the whole process of how they came to the United States, their story and their background. I wanted to combine the religious aspects of my mom with my parents’ story, so I made an altar for my parents.

Diving into my roots has made me realize this art of telling a story is activism in a way, but I wouldn’t consider myself an activist. A lot of people will define me as an activist, but I don’t believe that I am. I think being born into an oppressed community just makes you radicalize. You have to be radical all the time, because people will look at you as being radical if you’re just trying to live life.

What advice would you have for students who are getting pushback from institutions as they try to tell their own story?

I went back to Moore after five years of not going back, and I did a workshop with students about channeling in your imposter syndrome. At that age, you compare yourself so much to other artists, and you compare yourself to the ones that are privileged. My advice to them was just like, “You should be proud of yourself to be in this institute. Give a big ‘fuck you’ to the people that are racist towards you. There’s days that you will want to give up, but having a good community behind you helps a lot.”

To answer your question, the advice I would give to kids in institutions would be to question everything and challenge your professors. Just stand your ground and let them know, “The art that I make is not meant for you. At the end of the day, I’m graduating and I’m going to do my own thing.” It’s the same thing as telling your parents, “I’m going to be an adult.”

I told them, “Live for yourself. These academic people, your professors, they were once young, too, and they got to where they’re at because they started living for themselves. You should start living for yourself, too. I understand the insecurities and I understand it’s scary out there, but at the same time have that mindset of like, Fuck it, I’m going to do me. It’s going to be harder or take more time for me, but I’ll also fucking do it too.

What brought you to Philadelphia and what has kept you engaged with the city?

I wanted to move out of my parents’ house so badly. I knew I wanted to live in a city, but I was first generation going into college, so I had no idea that there were different levels of degrees. I didn’t know what bachelor’s was. I only knew that you went to college, you got a degree, and you started working. So I went to Mercer County Community College [near Trenton, NJ]. I went in there for radiology. I was going to be in the medical field. Then I realized that I wasn’t prepared for the intensity of it, but I knew I wanted to do something with the arts if I didn’t do the medical field. So I switched over to graphic design and illustration.

During that time, I met one of my classmates; she was a little bit older than me, and she saw how passionate I was with my art, and was just like, “You should get a bachelor’s.” And I was 19 or 18, and I was just like, “What is a bachelor’s?” And she had to explain it to me. And then I went to my advisor. She went to Moore so of course she’s going to say, “Go to Moore.”

If you are someone who doesn’t have any relatives that went to school and you’re the first one, and you’re in an environment that you desperately want to get out of, you’re going to take that opportunity. You’re going to think that you’re a special person, and that’s what I fell victim to, in a sense. College fucked me up so much that I stopped being an artist. I was just working and trying to survive. I stopped creating.

What led you back to art making?

I started curating. I started organizing. I started to be more involved in Shut Down Berks. I used my butterfly design for my thesis and I gave it to the coalition. I was just like, “This is a piece that I made for my thesis, but let me know if this is something that we could use for the banner” and they used it and that’s what becomes the principal imagery when they think about Shut Down Berks.

I started working for the Painted Bride for this temporary installation. We hired Manny Vasquez as a photographer and then Manny and I became close. He asked me if I want a job at Fleisher Art Memorial. That’s when I started creating again, because being in an environment with children who are also children of undocumented folk, who are also bilingual or who didn’t know English, I started seeing myself in these kids.

I always tell myself if my teenage self could look at all the shit that I’ve done now, they would be happy. They would be really satisfied about everything. I do it for them and I do it for the children here in Philadelphia who don’t have the privilege to go to these nicer schools and who don’t have access to art. I never thought I was going to be a teaching artist. But here I’m becoming that teaching artist and just becoming the fun art teacher I desired when I was a kid.

You are a 2023 recipient of the Leeway Art and Change Grant, can you talk about what project you received the grant for?

Jasmine Rivera, who is the co-founder of the Shut Down Berks Coalition, connected me to the Free Migration Project. They had this campaign, End Medical Deportation Campaign, due to one of the community members who is from Guatemala, and her brother had to have an intense surgery with a lot of intense aftercare but he was listed for deportation right after surgery. If he had been deported back to Guatemala, he wouldn’t have been able to have the resources that he had here, and he would’ve eventually died over there.

This person [name withheld for her protection] reached out to Adrianna Torres-García, who’s the Deputy Director of the Free Migration project. So Jasmine and Adriana and this community member all worked together to get this campaign started. Adriana was just like, “Maybe we could use art for this campaign, and I would like to have a logo.” It was still up in the air with exactly what we wanted, but Adriana and I worked on the application together. When I got the grant, I was in disbelief.

A bill to end medical deportation was being presented around the same time that we were able to get the grant. Before that, we talked about having banners, making the logo, and all that stuff, but then Jasmine and Adriana were like, “Let’s do a workshop, and bring the community members into it so that we can discuss more about this.”

We weren’t sure if the bill was going to pass, so it was either going to be a workshop to make people understand what’s happening and to keep fighting for it, or a workshop to celebrate. One week before the workshop, the bill does pass, and Philadelphia becomes the first city to end medical deportation. We did the workshop here at Fleisher and I did screen printing. We did tote bags and T-shirts, and we talked about it with the community. And we did a potluck, and we had tamales, and conchas, and all that beautiful food.

To end those medical deportations was a win for undocumented immigrants to be able to feel safe to go to the emergency room without feeling that they’re going to be deported. But at the same time, not a lot of people know that this is a thing.

Right now, we’re planning to do more workshops to educate the doctors to have them understand ways to protect your patients if there is a deportation order. There’s always a way to stop a deportation, but they need to be able to deescalate the situation. These workshops help doctors in case they do see that it’s happening, to be able to interfere and state, “According to this law, this patient is allowed to be here even though they’re undocumented.” The whole point is to get other people to understand this and help undocumented people to understand that, “You have every right to stay because you are a person and not just a number.”

Logan Cryer is a curator based in Philadelphia with a penchant for local art histories. They currently serve as the Co-Curator of Icebox Project Space and they like to rewatch documentaries.

This story is part of a partnership between The Philadelphia Citizen and Forman Arts Initiative to highlight creatives in every neighborhood in Philadelphia. It will run on both The Citizen and FAI’s websites.

![]() MORE FROM OUR ART FOR CHANGE SERIES

MORE FROM OUR ART FOR CHANGE SERIES

Chela Ixcopal. Photo by Isabel Kokko for Forman Arts Initiative.