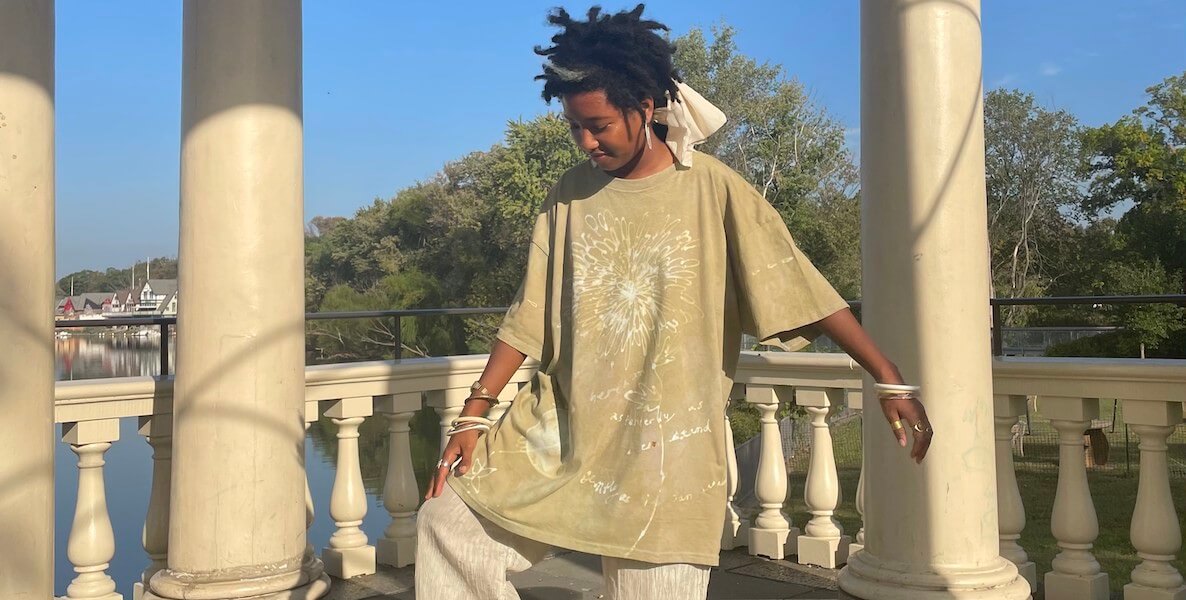

Suldano Abdiruhman is a Philadelphia-based interdisciplinary artist who reaches deeply into her own life and explores her own surroundings to work through essential concepts like grief, spirituality, bias, and communication. Although such themes might suggest otherwise, Abdiruhman says the driving force behind her art is: hope.

“I believe in the act of building or imagining as inherently optimistic, it implies a belief in a future and it is generally a universal (not just human) value,” she says.

Abdiruhman is a member of the artist-led Landline Collective and one of 16 recipients of a 2022 P(h)ew Microgrant, created by 2021 Pew Fellow Rami George’s commitment to redistribute 10 percent of their Pew award to QTBIPOC artists in Philadelphia. A descendant of artists and a physicist, Abdiruhman’s artistic practice is experimental, research-informed, and documentarian, and spans a diversity of media including textile, weaving, drawing, sculpture, and more.

When describing her work, it is evident that she sees the act of creation as educational and symbiotic, with ideas and materials possessing both autonomy and wisdom to share, if listened to. “I believe that ideas have spirit — they are bossy but they are also earnest,” she explains.

“There is a tenderness and desire to create space for one another I feel in the art community here. People want to understand and uplift one another rather than compete for resources. I also just love being surrounded by people who are willing to get their hands dirty.”

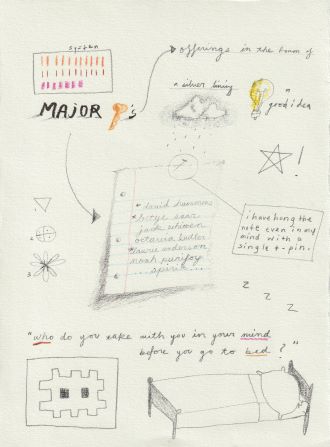

Rigid shapes and grids ground her more conceptual works like building the world i and ii; whimsical phrases written (sometimes-messily) in pencil like cheer up! (-: counter earnestness with humor in paintings like right where I left it.

In partnership with the Forman Arts Initiative, The Citizen reached out to Abdiruhman to find out more about her work. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Morgan Nitz: What brought you to Philly from Baltimore, Maryland?

Suldano Abdiruhman: I was looking for jobs related to my textile degree, but I was also eager to be in a city where I could get to know myself with some distance from my hometown. The proximity to New York galleries, places like the Fabric Workshop and artist-run spaces in Philly were enticing to me as well, but because of the pandemic I found myself freelancing and doing more interpersonal relationship-building rather than jump-starting my career.

In many ways, this has served me so well: I have been able to fold into the community here before entering the hustle and grind of post-grad life.

How did you get started making art? What draws you to such a diversity of media, and what do those media allow for?

I was encouraged to make things as early as I can remember and have a few artists in my family. My mother and her father painted, and my paternal great grandmother was a weaver, so it’s also in my blood. However, I feel like my greatest influence has been my environment.

Growing up in Baltimore, a majority of my life has deeply influenced my sensibility for material and color i.e, plaster, reclaimed material, dirt, wood. The lavender and orange reminiscent of smog in the city skyline are unmistakable in my work. I find beauty in everything, even concrete and litter, because, to me, they are artifacts or information.

I spent a few childhood years in St. Croix USVI [U.S. Virgin Islands], and was born in Ramah, New Mexico. I have had the privilege of returning to both places in the past few years, and these trips were revelations in terms of realizing their influence on my work.

Whether spiritual, artistic or utilitarian, I found commonalities between my own work and the culture of both places. Color, form, weaving natural materials, reclaiming what is considered refuse, a reverence for the natural world and an understanding of our connection to all things were some of the most common similarities.

In terms of my use of many different media, I believe that ideas have spirit — they are bossy but they are also earnest. Most often ideas or concepts need to be communicated in a particular way, or they lose their integrity. For the sake of coherence (and also my own sanity), I do try and stick to the above media, but I also believe that if an idea is coming through an artist, it is their responsibility to carry it out in the media that best conveys the message. If not, it finds its way to the next person who can.

Your artist statement describes your process-based artistic practice as “rooted in empathy, experimentation, and curiosity about the mystical.” Can you describe what this means to you and your approach to artmaking?

I believe my role as an artist is similar to that of a historian. As in, part of my work is to document or filter the world around me through my own hands/emotion/particular sensibilities. This requires acknowledging that I have bias, but also working with the intention to act as a kind of mirror for those around me — this is where empathy comes in.

My interest in the mystical has entered in the past few years as I begin to explore the growing overlaps in fields such as quantum physics, spirituality and neuroscience. Experimentation is generally connected to my dedication to my craft. The more I play, experiment, and research, the deeper the relationship I develop with my material and the easier it becomes to make it malleable — sort of similar to learning a language.

I believe ideas have spirit, so my approach to art-making is very much like that of a collaborator. I strive to be attentive, respectful, open-minded and curious, because I believe the work that comes from this set of values allows the audience many ways to enter and engage with me and what I make.

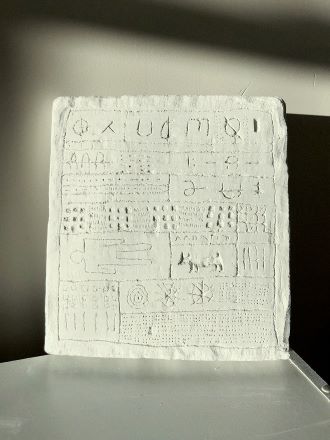

Time can be the best teacher, particularly for things as powerful as grief and mortality, which is proven in your works building the world i (2017), and building the world ii (2021). What led you to revisit and expand on the original piece, a memorial to your late grandfather?

building the world i was a very raw and immediate way for me to begin processing my grandfather’s transition. At the time, it felt like pure emotion. However, when I revisited the work after the haze of fresh grief, I found a trail of breadcrumbs which felt partially placed by my grandfather.

He was a physicist and engineer — deeply interested in the way our world works on an elemental level. He encouraged us to be curious about that kind of thing. On his deathbed, he seemed in an almost transcendental state.

At one point, he spoke about how he was lying there, “building and rebuilding the world” in his mind. This was the catalyst and title of the first work, but in the second piece I began to understand what he may have been speaking about.

The symbols that recur in my work — pictorial symbols, bricks, ancient communication systems, and repetition/pattern making — all have a common theme. They are ways we use to either convey our own internal worlds or build external ones that we have imagined internally. I believe in the act of building or imagining as inherently optimistic, it implies a belief in a future and it is generally a universal (not just human) value.

This series helped me to verbalize this idea I was revisiting over and over again in my work. These pieces which carried seeds of hope were made following periods of grief or great transition in my own life, so I am also thinking about cyclicality and nonlinear time.

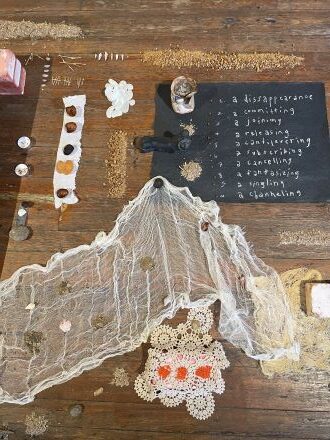

You were very intentional in the selection of materials (grids, poems, fabrics) and words (transformation, death, rebirth) for the building the world pieces. What is described through the relationship of these objects, as opposed to by each individual object on its own?

I find when dealing with concepts as lofty as death, time, or transformation, I am inclined to use materials that have a rigid structure or defined container. This is both a formal and a conceptual decision — as it is a way to create balance in the work.

Often when dealing with the mystical or spiritual, there is a Western tendency toward skepticism rather than the respect that comes with fields based in empirical or quantitative research. This is changing. However, I am still hyper-aware of this as an artist, and as a Black person. I’m often asking myself what the decisions I’m making in the studio are trying to prove, who they are for.

In this case, I see many overlaps between the material and conceptual matter. For example: grids/fabric as a metaphor for spacetime, or poetry as an attempt to express the experience of transformation. My desire, however, is to get to a point of confidence in my studio practice where I can work with these concepts head on.

“I find beauty in everything, even concrete and litter, because, to me, they are artifacts or information.”

Can you tell me more about Landline Collective, how it was formed, and its mission? Are there opportunities for others to get involved with the collective?

Absolutely! Landline was founded by myself and my collaborators and fellow artists Jenna Staffieri and Pony Lin. We met in undergrad, ended up in Philly together, and decided to create a collective of our own as a way to connect with the artist community we were entering.

Organizing events during the pandemic became less and less of a possibility. So, the idea for a quarterly newsletter was born as an alternative. Baltimore has a huge culture of zine-making, which was a huge inspiration for us. The idea was for an open-format digital newspaper with a quarterly theme.

So far it’s been great fun, and we’ve connected with folks all over the country and even internationally. There’s an issue coming out soon under the theme Magic and then likely a hiatus for a while, as we are planning some more public offerings. If you’d like to follow you can join our newsletter here or follow us on instagram @landlineco for announcements about future issues!

You were a recipient of a $500 P(h)ew Microgrant. Have you been working on a project as a result of, or related to, the microgrant?

I am! The cohort of fellows will be activating the Leonard Pearlstein Gallery at Drexel in April of 2023, with studio spaces and public-facing workshops, installations, and open studio days. I am hoping to create some larger-scale painted textile works with access to this larger space, as well as potentially some public performance works.

I’ll be posting more about these offerings as we near spring, which you can find via instagram @meltingpot.world!

What is your favorite thing about the Philly art community? Philadelphia in general?

Philadelphia’s art community reminds me so much of Baltimore. I sort of blindly moved to this city thinking that it would be akin to the size, access and highbrow culture art scene of New York. Baltimore was all I knew. I was surprised to find what feels like a sister city with many DIY-run art spaces, a deeply rooted abolitionist/anarchist politic, and an accessible and wildly diverse art scene.

There is a tenderness and desire to create space for one another I feel in the art community here. People want to understand and uplift one another rather than compete for resources. I also just love being surrounded by people who are willing to get their hands dirty.

Philly is gritty like Baltimore. Sometimes you are working with very little, which is often fertile ground for brilliant and imaginative world-building. This culture of possibility means there are folks all around me turning ideas into events or fully realized projects without the permission that comes with capital or formal support, it is so inspiring!

What are you excited about right now?

Right now, I am deeply excited for the restorative, reflective time that winter will bring. I am a busybody and for many years have dreaded the slowness that comes along with the cold. But I am coming to embrace this quiet. It allows me to hear my own thoughts.

I am looking forward to using this time to deepen my research, vision for the new year, and plan projects, as I am applying to several residencies for 2023. I am also looking forward to more time in saunas this winter!

Are there any upcoming opportunities for people to see your artwork in person?

Besides the show in spring as part of the P(h)ew grant, I am also a featured artist in Islam and Print, a fellowship connecting Muslim artists in the Baltimore City area. It is curated by two curators and friends of mine, Safiyah Cheatam and Dan Flounders. There will be a physical show at Current Space in 2023 of editioned prints made during the fellowship — dates are tentative, but keep an eye out, as it is a fantastic lineup of artists!

Correction: A previous version of this story said writer Morgan Nitz was the Digital Engagement & Event Specialist at the Office of Arts, Culture and the Creative Economy. Nitz has since been promoted to Community Engagement and Communications Manager for that office.

This story is part of a partnership between The Philadelphia Citizen and Forman Arts Initiative to highlight creatives in every neighborhood in Philadelphia. It will run on both The Citizen and FAI’s websites. Morgan Nitz (she/they) is a queer interdisciplinary artist and writer in Philly, and the . Their work has been shown at The Institute of Contemporary Art, Vox Populi, Pilot Projects, and other venues; they completed a residency at Jasper Studios; and were the co-inaugural curator of Straw, Tyler School of Art’s AV-closet-turned-Alumni-gallery. Follow them at morgannitz.com | @son_of_m.a.n

This story is part of a partnership between The Philadelphia Citizen and Forman Arts Initiative to highlight creatives in every neighborhood in Philadelphia. It will run on both The Citizen and FAI’s websites. Morgan Nitz (she/they) is a queer interdisciplinary artist and writer in Philly, and the . Their work has been shown at The Institute of Contemporary Art, Vox Populi, Pilot Projects, and other venues; they completed a residency at Jasper Studios; and were the co-inaugural curator of Straw, Tyler School of Art’s AV-closet-turned-Alumni-gallery. Follow them at morgannitz.com | @son_of_m.a.n

![]() MORE FROM OUR ART FOR CHANGE SERIES

MORE FROM OUR ART FOR CHANGE SERIES