Philadelphia’s Republican City Commissioner Al Schmidt, whose matter-of-fact demeanor and competence under pressure provided reassurance throughout 2020, has announced he won’t seek another term as Commissioner in 2023.

The announcement is disappointing but understandable given the many bridges Schmidt had to burn with his party to do his job with integrity this year, and the frightening harassment he and his family withstood from disgruntled Trump supporters who wanted to see Schmidt play along with the official party messaging about mass fraud in Philadelphia.

It’s worth taking a step back to note the strange circumstances under which the office found itself momentarily competent, and the unlikelihood it will stay that way.

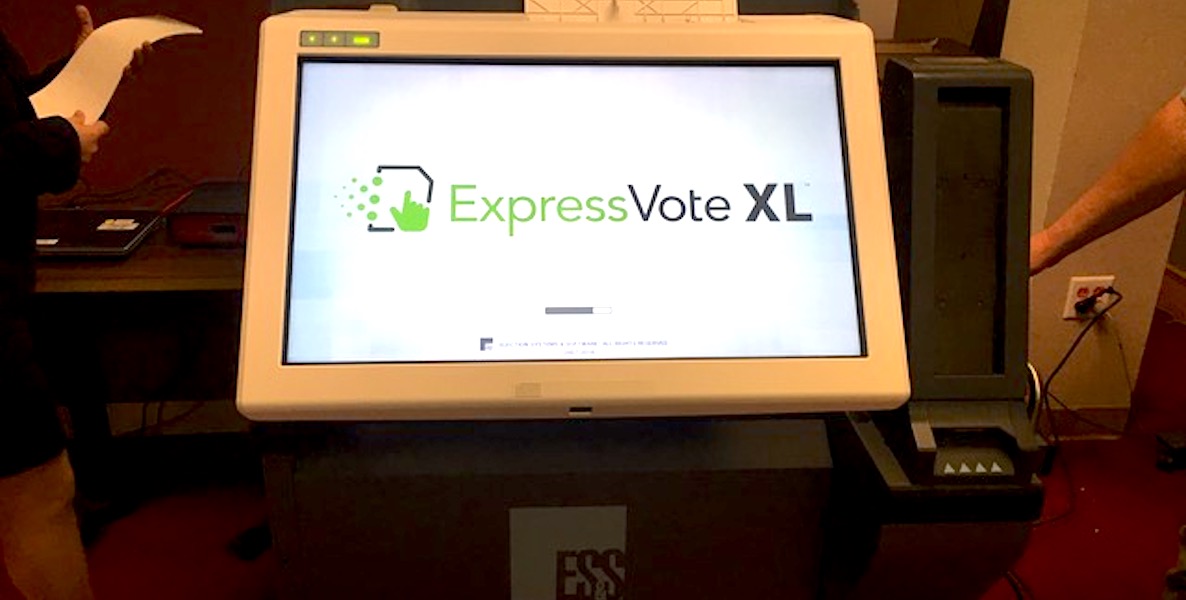

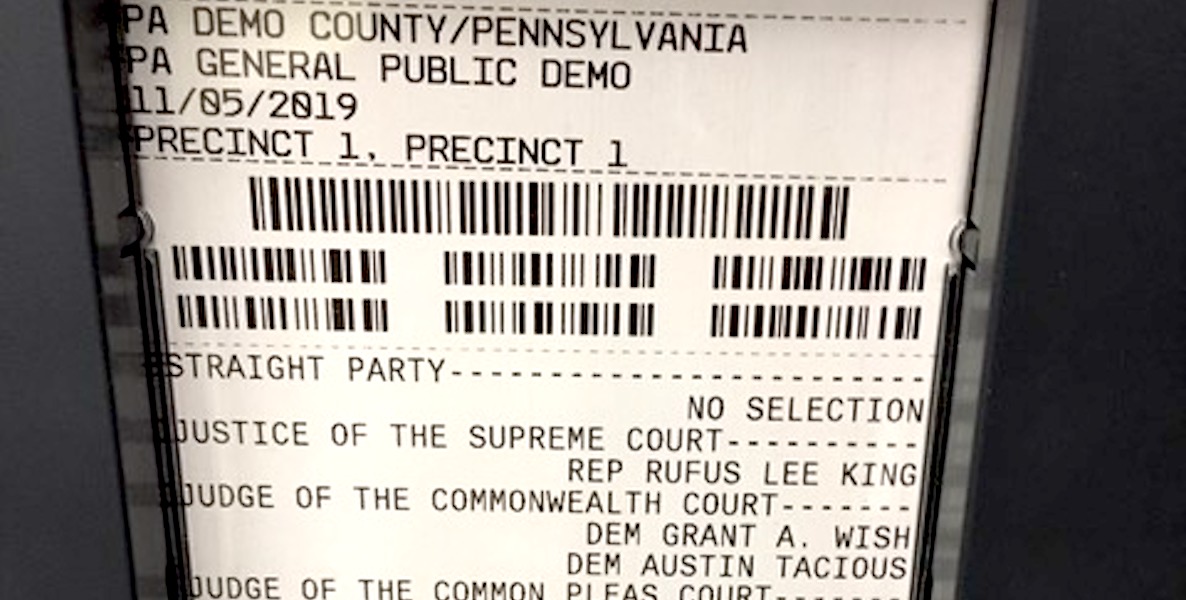

The City Commissioners’ heroism in the face of a hostile political environment, and the relative lack of major errors despite administering a brand new voting system in a historically high-turnout election, all under pandemic conditions, deserves high praise.

But in light of Schmidt’s announcement that he won’t seek re-election, it’s also worth taking a step back to note the strange circumstances under which the office found itself momentarily competent, and the unlikelihood it will stay that way.

The Commissioner’s office has never been well-governed throughout its history, and I believe this has to do with structural issues more than personnel, but it’s also the case that it tends to be one of the easier for the Democratic and Republican Party organizations to staff with party operatives.

There are three elected positions, and there’s a minority-party requirement in the city charter, similar to other county commissioner elections in the southeast counties. The minority party requirement works similarly to the one that allowed Kendra Brooks to win election to City Council as a non-Democrat, in that each party can only nominate two candidates in the primary, but there are three seats in total. To date that’s typically yielded two Democrats and two Republicans.

In the 2011 election, Stephanie Singer and Al Schmidt won election to the Commissioners’ office as insurgents in their respective primaries, replacing Joe Duda and Marge Tartaglione. They joined Anthony Clark, the famous no-show Commissioner, who was elected in 2007. That 2011 election began to turn the tide toward somewhat greater competence, but unfortunately hasn’t made enough of a dent. As one example, that group presided over the notorious provisional ballot mess in 2012, where over 27,000 registered voters had to use provisional ballots after they didn’t appear in the poll books—double the number that had to in 2008.

![]() This is the problem with hiring people to administer our elections via an election. The ability to win a popularity contest, which every election is, doesn’t come with any requirement that they have any relevant experience whatsoever. It’s the equivalent of electing a district attorney whose first day on the job is also her first time in a courtroom.

This is the problem with hiring people to administer our elections via an election. The ability to win a popularity contest, which every election is, doesn’t come with any requirement that they have any relevant experience whatsoever. It’s the equivalent of electing a district attorney whose first day on the job is also her first time in a courtroom.

And the issue is magnified by the fact that, for the majority of candidates who successfully run for Commissioner, the job is substantially bigger and more complicated than anything they’ve done before, and then when there’s turnover, people tend to be starting from square one.

In the 2020 election, the Commissioners’ operation benefitted from a vast infusion of outside funding and technical support coming into the city that’s unlikely to reappear in future elections.

As we’ve seen over the years, the office is almost entirely impervious to accountability through the elections channel, and this is a function of government too important to leave up to the local parties’ patronage picks.

And then the trouble is that when Al Schmidt leaves, the most likely outcome is that things will take a hack-ier turn, with Republicans perhaps more likely to nominate someone more in tune with the party’s current, more conspiratorial flavor.

Without Schmidt’s own idiosyncratic perspective as a bulwark, we might instead have had a Republican commissioner who wanted to be a media star from the opposite vantage point—stirring up trouble internally, cooking up “evidence” of voter fraud to be used by the national Republican Party or Fox News, and otherwise complicating the vote-by-mail rollout with the goal of suppressing voting.

And that is still who we could get after the 2023 elections if the Republican Party doesn’t nominate one of Schmidt’s deputies like Michelle Montalvo or Seth Bluestein, and instead goes for someone Trumpier.

Imagine a Commissioner’s office run by Lisa Deeley, Omar Sabir, and Billy Ciancaglini. It’s not a group that inspires a lot of confidence, and structurally, there’s no real reason to expect the quality of election governance to improve—and lots of reasons to expect it to decline.

Under the circumstances, the value of eliminating the Commissioners’ office as an independently-elected concern and transitioning election administration to a Mayor’s Office of Elections is more pressing than ever.

In a world where Philadelphia modernized its election system and replaced the City Commissioners with an Election Director, turnover wouldn’t guarantee a seismic reduction in the level of expertise. In fact, turnover would likely work in the opposite direction.

It’s easy to imagine, for example, a mayor bringing in an Election Director with direct experience running a vote-by-mail system in another state in response to a state-level move to no-excuse absentee voting. As it is, the Commissioners are always learning on the fly.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

Header photo courtesy Governor Tom Wolf / Flickr