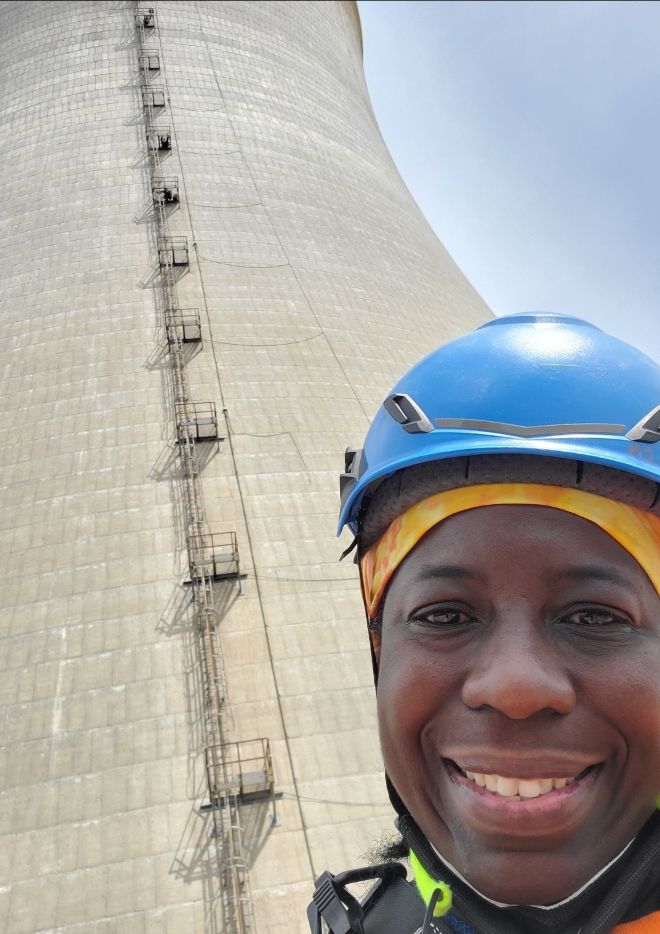

Elaine McGuire, the first woman electrician to climb the Limerick Nuclear plant cooling tower, in 2021, was also likely the first person to climb the 508-foot tower while singing — specifically, songs from the Wizard of Oz and The Sound of Music.

Listen to the audio edition here:

Part of a team installing new aviation lights on the plant, McGuire belted out show tunes as a way to forget how high she was climbing — around 50 stories — and the fact that all eyes were on her from below.

“All the guys were clapping and cheering for me,” she says. “I was just like, oh my god, you’re going to make me cry.” She still keeps a printout of the article PhillyVoice published at the time on the desk in her office. She grins in the image, which — with its row of hard-hatted electricians standing against a backdrop of sky — hearkens back to Depression-era shots like the famous “Lunch atop a Skyscraper.” (It featured a team of construction workers — all men — eating lunch on a girder while building Rockefeller Center.)

It’s one of many marquee moments in McGuire’s career. She’s worked on major jobs at Lincoln Financial Field and Citizens Bank Park; served as a steward for her union, IBEW Local 98, during the Convention Center’s expansion, and as a foreman on the Comcast Technology Center; and she met Kamala Harris during the 2024 Presidential campaign.

This is all the more remarkable because McGuire is a Black woman, and Black women are underrepresented in all of the building trades. Women make up 2.9 percent of electricians, according to 2024 Bureau of Labor Statistics data. Black people make up 9.2 percent of the field. Philly’s trades have long struggled to diversify union membership; Ryan Boyer, the first Black leader of the Building Trades Council, has made it a priority since taking the helm in 2011.

Today, McGuire is fighting to change that. She launched the Philly chapter of the Electrical Workers Minority Caucus (EWMC) in 2023, and runs a pre-apprentice program, Rosie’s Girls, to help young women get interested in careers in the trades.

“When Elaine got in, there was not a lot of female representation in our industry,” says Mark Lynch, Jr., business manager for IBEW Local 98. “She was one of the first people to really get in and prove to the younger women that this can be done.”

From hairstylist to electrician

Before going back to school to become an electrician, McGuire worked as a cosmetologist. She hadn’t thought much about a career in construction until she heard Lincoln University was piloting an education program in building maintenance. She was happy with her career, but she’d “always wanted to drive a backhoe,” she says.

So she signed up and started taking classes in carpentry, plumbing and electrical work. She excelled in the electrical module, the program offered her a job as a student teacher and she began chatting with union electricians. One of them asked: Would she consider making a career switch?

“I’d never thought about it. I didn’t know anything about unions,” McGuire says. “It was not something that many women knew anything about, especially African American women, because it’s a majority White field.”

Eventually, McGuire quit her cosmetology career and became an apprentice, graduating to become a journeyman electrician in 2004.

While she studied, McGuire worked with the construction firm Riggs Distler, and felt lucky that they treated her like family; one foreman, Mike Rakus, took her under his wing. From him she learned how to work on high-voltage projects and how to install rigid conduit, a complex process that protects electrical wires in high-impact areas — opportunities other apprentices didn’t always have.

“He said, you’re going to learn everything I know. And that’s how it was,” McGuire says. “Everywhere he went, I was right there.”

McGuire loved working as an electrician, but almost immediately she encountered challenges her male peers didn’t face. Jobsites didn’t often stock tampons or pads. The personal protective equipment they were given didn’t always fit properly because it was designed for men’s bodies. Mothers, like McGuire, were often met with criticism for taking time off to tend to their children.

“It was frowned upon if you said, I have a sick child at home and I need to take them to the doctor,” McGuire says. “Some men in construction would say, that’s why women shouldn’t be out here in the field.”

More problematic: Many women didn’t feel like there was anywhere they could go with these concerns. Most of the foremen and union stewards on job sites were White men. If you felt uncomfortable talking to them and went to a union member services representative, you’d usually also be met with … a White man. “That was the hardest part,” McGuire says. She saw many women leave the field because no one was listening to their concerns. “It was rough when I first came in. You had to be really thick-skinned.”

Launching EWMC

McGuire has an electric personality (pun intended). People are drawn to her laughter and easy smiles. She also has a penchant for helping others — she studied theology and became an associate minister at her church in West Chester. She knew she’d had unique opportunities in her career as an electrician, in part because of strong mentors like those she found at Riggs Distler, and she knew she “wanted to do more … for the community, more for those that are coming behind me,” she says. After talking to women on job sites, including those at the Linc and Citizens Bank Park, she decided to start a group for women in her field to support one another.

Dubbed Women in the Trades, it brought together women in carpentry, plumbing and other building trades — not just electrical work. The group met monthly, talked about the challenges they faced and helped one another through them.

McGuire ran Women in the Trades for about five years, starting in 2006, before she became too busy to continue the organization after becoming a steward for the Convention Center expansion. (A steward is a rank-and-file union member who acts as a representative for the union on the job).

These leadership roles allowed McGuire to continue to be an advocate for women, people of color and younger electricians in the trades. She’s helped women who struggled during their apprenticeships go on to become foremen (forewomen?). Her nephew followed in her path and became a foreman electrician and her son recently completed his apprenticeship.

“People would see how passionate I was in my field, and they respected me for that,” McGuire says. “I always tell everybody, watch how you carry yourself, watch how you treat others, because someone’s always watching.”

When Lynch took over as business manager of IBEW Local 98 in 2021, after longtime business manager John Dougherty was convicted of federal bribery charges, he encouraged union members to start a women’s committee and a chapter of EWMC.

McGuire was one of his first hires. She now works as a member service representative for the union, serves as the senior advisor for the women’s committee and president of EWMC, which officially launched in 2023. The group hosts socials, volunteers together, works with other groups within the union, like the veterans committee, and helps support members in attending events like the national EWMC conference. The EWMC chapter started with nine members. McGuire has grown it to about 86.

For Nora Taylor, a journeyman electrician and member of IBEW Local 98, McGuire is a mentor. Taylor had been following McGuire’s career since she climbed Limerick’s nuclear plant. When they met for the first time at a union meeting, she admits to “fangirling a little bit.” Because of McGuire, Taylor joined the women’s committee and traveled to the EWMC national conference in 2023. She now serves as the secretary for the Philly chapter of EWMC.

“I honestly wouldn’t have known anything about it if it weren’t for Elaine,” Taylor says. “She advocates for women to be treated fairly, to be treated the same way men are treated.”

Training the next generation of electricians

Tracking the diversity of building trades union membership has long been difficult in Philly, largely because for years unions didn’t report on the demographics of their membership. Under John Dougherty, IBEW Local 98 declined to provide information on the racial demographics of its membership for a 2009 report compiled by the Nutter administration. An investigation from 2012 found that union workers in Philly were 99 percent male and 76 percent White. Mayor Kenney promised to diversify, setting a goal of making sure that at least 45 percent of workers on city-funded construction projects were Black. But by 2018, only Local 542, which represents operating engineers, had a mandate to report racial makeup of its membership.

That’s changed in recent years. In 2021, Boyer became the first Black person to head up the Philadelphia Building Trades. The same year, Lynch took over Local 98 and made diversity a priority. The union tracks its demographic data in real-time and has found that between 32 to 35 percent of its membership are now women and minorities. They’ve also added support for women joining the trade, like a private room for breastfeeding mothers, at their headquarters in the Navy Yard.

McGuire says the union has become visibly more diverse since she first joined, when she was one of two women to graduate from her apprenticeship class. (The other woman has since left the field). She’s now heading up Rosie’s Girls, the union’s preapprentice program for girls aged 14-17, to bring more women into the fold.

Launched in 2022, Rosie’s Girls teaches women about the basics of electrical work over the course of a 63-hour program. (Sometimes the program runs over nine weeks or two weeks in the summer). The program is named for Rosie the Riveter, the famous flexing, bandana-sporting woman from a World War II-era campaign that encouraged women to take up factory jobs traditionally held by men. At the end, they host a graduation ceremony with a dinner for the girls and their families. McGuire has spoken at the event.

“It’s something to see her face and her emotion when she gets up there and speaks in front of not only the kids, but the families. You can tell she cares,” Lynch says.

Completion of the program qualifies women to apply for Local 98’s apprenticeship programs. Before heading up the program, McGuire served as one of its instructors and worked closely with Teila Allmond, who championed it for years.

She loves seeing the girls return to apply for apprenticeships. One ran up to her and gave her a hug when she came to apply. So far, about 100 girls have completed the program.

Says McGuire: “You plant a seed in them, and now you’re watching them grow.”

![]() MORE ON ECONOMIC EQUITY FOR WOMEN

MORE ON ECONOMIC EQUITY FOR WOMEN