Ken Weinstein doesn’t exactly seem like he’d be a pro-labor roustabout. He’s in real estate, after all, owns the local Trolley Car retro-diner chain, and has an extensive history of small business ownership. But he’s also a businessman with a social conscience. And that makes him the perfect person to head up Wage Change, a movement he launched in January to upend the embarrassingly low minimum wage in Pennsylvania, using that most American of tools—free market capitalism.

Weinstein started Wage Change in January, with the hope of raising the minimum wage to something at least livable in Philadelphia, one business at a time. Now, he’s no longer simply a businessman; he’s a wage increase prophet. Weinstein spends a considerable amount of time these days proselytizing to Philadelphia-area businesses to commit to his pitch: an $11 minimum wage by 2020. So far, he says, more than 40 business have committed to the minimum wage increase, four months into his campaign’s existence.

“And by the end of 2017, I want to have 1,000 business committed to Wage Change,” he says. “The volume of business signing up with us increasing more and more.”

Weinstein’s a former politico, a Penn graduate with a master’s in government administration and one-time chief of staff to former City Councilwoman Happy Fernandez; for the past couple of decades, he’s worked in real estate. He’s got the connections and skills, and he’s happy to do the heavy lifting for Wage Change.

“You know, it’s all politics. And once it’s in you, that love for organizing, it never goes away,” he says. “I love it.”

A higher minimum wage is good for business. It boosts morale and increases employee retention while decreasing turnover; studies have also shown that higher wages decrease absenteeism rates among employees. That means less time and money spent on training workers, and better customer service—which in turn means more business.

Unlike other big cities coast to coast, minimum wage in Philadelphia mirrors the federal hourly rate of $7.25. In New York City, businesses with at least 11 employees must pay them $11 an hour; for smaller companies, the minimum is $9. Boston’s minimum wage is now $11 across the board, and Baltimore City Council just passed a bill allowing for a $15 minimum by 2022. New York City, Los Angeles, and Seattle are all set to enjoy a $15 minimum in the near future.

In Philadelphia, according to MIT, a living wage would be closer to $12 than $11—and that’s just for a single person. For a person with a child, an adequate living minimum wage more than doubles. And, inflation and market forces drive up the living minimum nearly annually. For a family of two or more, living on one full time minimum wage income per year puts them below the poverty line, a contributing factor to Philadelphia’s soaring poverty rates. In Pennsylvania, minimum wage increases are functionally managed by the state legislature, which has proven to be uninterested in making any changes—and is not likely to do so any time soon.

Meanwhile, the federally-mandated wage is one reason for the seemingly intractable quagmire of the dissipating middle class. Reagan-era union busting and continuous pro-business legislation have stalled any movement on the minimum wage. The last time the wage was worth more than $8 in 2017 cash was 1983; the federal minimum was worth nearly $11 in today’s value in 1968.

During last year’s Presidential campaign, Hillary Clinton endorsed increasing the federally-mandated minimum wage to $12 an hour, and the Democratic Party Platform included a minimum wage increase to $15. That met with all kinds of backlash: Politically-moderate business owners said the Party’s proposed increase was far too steep; the far-ish left and Berniecrats contended that a $15 minimum was the only way to ensure that all minimum-wage employees, from the country to the city, received a livable income.

Weinstein’s proposed $11 is nowhere near as ambitious as either of those proposals. But it is something else neither of those were: Voluntary.

“Most businesses that sign up for Wage Change, I think, support a higher minimum wage change if it were [mandated] across the board,” says Weinstein. “But $11, we think, is manageable as part of a voluntary effort.”

A target date of 2020, he says, will give business owners enough time to reckon with their commitment—to move money around to deal with the eventual hike of over $3 per employee, or to give them a small, workable pay increase every year, ultimately leading to that goal. Weinstein says Wage Change arrived at the $11 number not through any market research or paid studies. As a matter of fact, he got to the number mostly by gauging the interest of potential partners. Weinstein wanted Wage Change’s pitch to be workable for anyone who wanted to get involved, from restaurateurs to retailers, and to allow them time to properly prepare.

Weinstein, who was looking forward to a minimum wage rise under a President Clinton, says he started Wage Change after the recent presidential and congressional elections made him realize there would be no action from Washington on this issue.

“A lot of us had hoped and thought that the minimum wage would change after the November election, and when it didn’t, we realized we had to act unilaterally,” bristles Weinstein. “There’s a lot of like-minded small business owners that saw minimum wage fall back over the years, and that’s not good for our employees or our customers.”

Weinstein spends a considerable amount of time these days proselytizing to Philadelphia-area businesses to commit to his pitch: an $11 minimum wage by 2020. So far, he says, more than 40 business have committed to the minimum wage increase, four months into his campaign’s existence.

Weinstein has a few reasons for thinking this. First, there’s the moral imperative: Weinstein’s Trolley Car diner brand is doing well, with two restaurants currently open and a third set to open in University City in the near future. Weinstein says there’s no way that he could countenance having his hardworking staff of around two dozen barely be able to make ends meet. Many staff at Trolley Car restaurants currently make 75 cents over the federal minimum, and Weinstein, like his peers, has pledged to increase the minimum that he offers employees to $11 by 2020.

But equally important to Weinstein is the simple fact that a higher minimum wage is good for business. It boosts morale and increases employee retention while decreasing turnover; studies have also shown that higher wages decrease absenteeism rates among employees. That means less time and money spent on training workers, and better customer service—which in turn means more business.

A higher wage also offers something to the fiscal conservatives among us: Many folks who work full time for minimum wage rely on some form of public assistance to supplement their meager earnings. While a minimum wage increase would almost certainly lead, short-term, to job losses, it would also, in the long term, pull people off the public dime.

In the end, though, Weinstein isn’t really into the red-versus-blue aspect of it all.

“I’m certainly more into the philosophy of a minimum wage increase than I am the politics,” he says. “I mean, we have Republican business owners that have signed on to Wage Change. Really, this is just something that needs to be done. And we’re probably going to have to be the ones who do it.

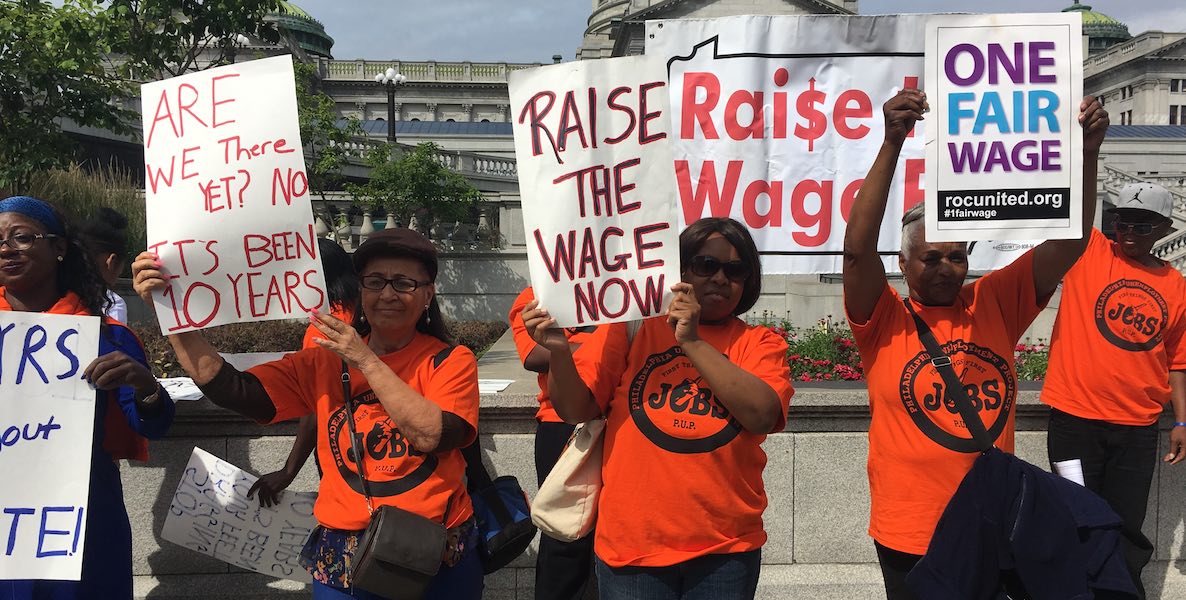

Header photo by Raise the Wage PA