My fervent desire to serve my community is what led me to a career as a teacher. But, it was anything but a straight path.

Although I had a social justice framework in my upbringing, had positive relationships and experiences with many of my teachers, and grew up in a household with a mother who taught, I did not initially consider teaching as my role in society. I just didn’t see myself as a teacher (of any kind). But, then something changed.

I was shot.

It was on October 4, 1992, when, as a 21-year-old African American male, I could have very easily become a statistic. Five months after graduating from IUP in rural Pennsylvania, I played in a football game on Bartam High School’s field. A young man said I tackled him too hard and wanted to fight—which we did. Afterwards, someone handed him a gun and told him to shoot me. I started to wrestle him for the gun. I failed and he shot me three times, severing an artery. He left me for dead.

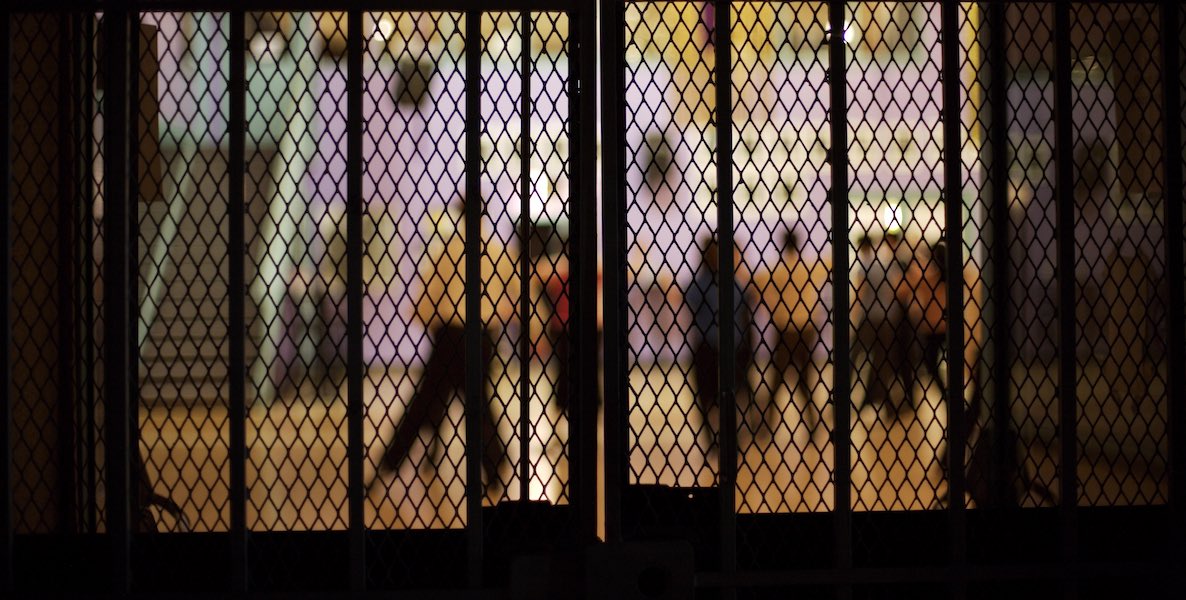

After 12 surgeries and several weeks in the hospital, teaching was still far from my mind. Instead, I decided to do some social work, which led me to a position as a counselor at the Youth Study Center (YSC).

I still think daily about the boy who shot me. As an educator, I see an angry kid from southwest Philly, a student who may have had all types of challenges and hardships, a quick temper, and far too easy access to guns. But, I also see a student who attended a struggling school.

My thinking at the time was that I needed to help kids like the one who had tried to kill me. I was angry. But I was also grateful that I survived. And I felt obligated to my community, to the adults who invested in me during my, at times, rocky teenage years. Where else could I find youth who might struggle with trauma and tempers, who may have far too easy access to drugs and guns, who dropped out of 8th grade? I thought The YSC is where I would make my mark in the community and how I would serve those who were in need of support, guidance, tough love, and compassion.

I didn’t make it through orientation.

Although the youth at the YSC desperately needed help, I yearned to find them before they entered such a place. I was depressed at the thought of seeing kids as young as 12 in what would constitute as a kiddie jail. I didn’t just want to disrupt the school-to-prison pipeline by working within the system. I wanted to join people working hard to dismantle it by ensuring our youth had a great education and great opportunities to match. I needed a proactive way to fight for justice and equity. I needed to be in a school.

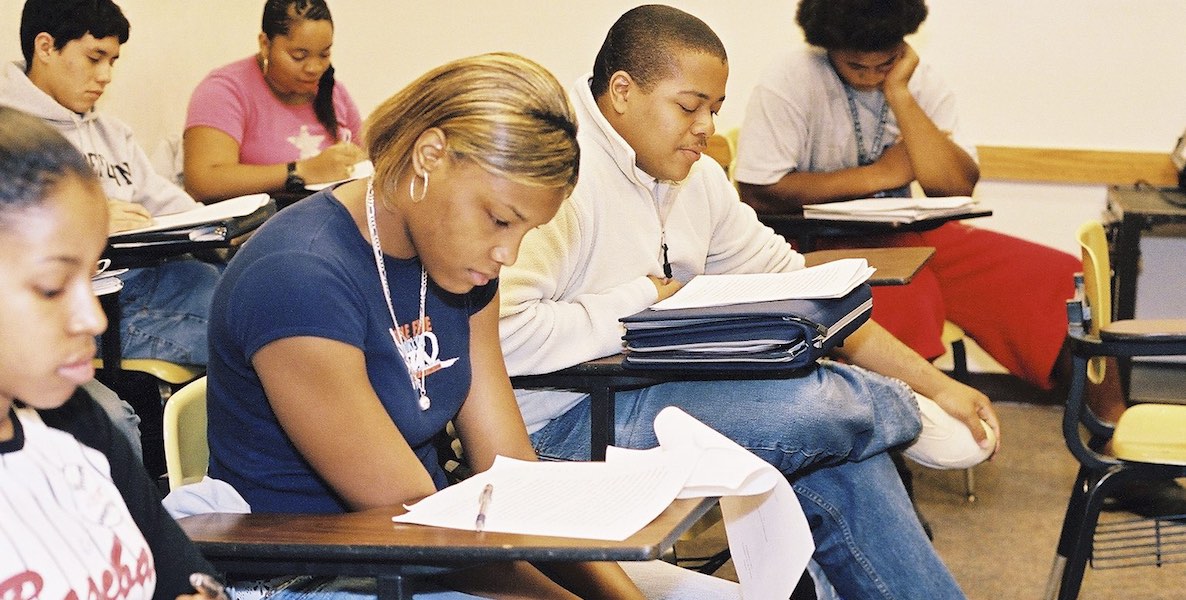

So, in the fall of 1993, I began my life’s work in southwest Philly at John P. Turner Middle School as an 8th grade Literature and Social Studies teacher. In an odd and delicious twist of fate, this is the same school that my assailant dropped out of. My destiny became crystal clear to me. I knew I was in the right place, doing what I was destined to do. Twenty-four years later, I remain immensely grateful to have the opportunity to serve our city in such a capacity.

Someone recently asked me which of my former students most inspired me. I have literally thousands to draw from, for both good and heart-breaking reasons. One of the kids who most inspired me is now dead.

Michael Cole. Charming, bright, hilarious, and witty. I had a monthly lecture just for him about coming to school consistently. When he and other students had academic challenges, we’d have Tecmo Bowl video game binges. I later rewarded him for his progress with a trip to Pittsburgh to meet some friends in the NFL. At a basketball all-star game, he had the typical nerve to challenge Jerome “The Bus” Bettis to a game of pickup basketball. Jerome Bettis played against Cole for 20 minutes, cracking up at the irreverent 8th grader’s incessant trash talking. I couldn’t wait to see what Cole would become. He had such boldness, intelligence, and a cool confidence I never could muster.

Cole was murdered while he was in high school. I still grieve him. He was my first murdered student. And, there would be more.

But there were many others; students who defied odds to show they were experts of every type of grit imaginable. There were the Iraqi refugees who battled all types of challenges; displacement, murdered relatives, utter shock, adjusting to life in two different refugee camps in two different countries before making their way to the new and unfamiliar challenge of being immigrant Muslims learning English in West Philly.

There’s the student who scored a 5 on five different AP exams. We didn’t even offer one of the courses. He taught himself. He’s studying at Oxford this year. There are the recent alumni who started a non-profit to tutor younger students at their alma mater.

I didn’t just want to disrupt the school-to-prison pipeline by working within the system. I wanted to join people working hard to dismantle it by ensuring our youth had a great education and great opportunities to match.

And I still think daily about the boy who shot me a couple of weeks after my 21st birthday, and who eventually spent eight years in jail. As an educator, I see an angry kid from southwest Philly, a student who may have had all types of challenges and hardships, a quick temper, and far too easy access to guns.

But, I also see a student who attended a struggling school. A student who struggled to find support amidst all the challenges he faced. I see a student who experienced what it was like to have adults give up on him early. Often. Consistently. What untold trauma was he battling? Instead of only wondering what was the matter with him, I often wonder what happened to him.

There are plenty of students who face similar circumstances. And, we know, that even the most struggling students have a better chance of navigating their situations with mentorship, support, listening ears, high and consistent expectations, and engaging school communities.

There are myriad reasons to do this work. Inspiration is all around.![]()

Today, the Youth Study Center—now known as the Juvenile Justice Services Center—still houses too many of our youth. And, we need far more educators—especially men of color—willing to enter the teaching profession. Our communities need educators to serve as “railroad switch” operators, supporting our youth in changing the trajectories of their lives and to help establish social justice in our communities.

Youth, like the one who shot me, are counting on this to happen.

Sharif El-Mekki is the principal of Mastery Charter School–Shoemaker Campus, a neighborhood public charter school in Philadelphia that serves 750 students in grades 7-12. El-Mekki will be contributing regular columns from the school front lines this year.