Last year, my wife Bet and I rented Big Pink, the fabled house in the woods just outside Woodstock, NY where, back in the 60s, Bob Dylan and The Band recorded a bunch of songs that helped set a generation free. We went with two of my long-ago college professors and close friends: Dr. Scott MacDonald, perhaps the nation’s leading authority on independent and avant-garde cinema; his wife, Patricia O’Connor, a veteran life coach; and Bob Baber, my one-time journalism professor who, in the 80s, swaggered around campus with Rebel Without a Cause-type energy, and went on to become dean of the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute.

Yeah, our getaway was a kinda parody of Big Chill-like self-consciousness, but the goal was to see one another, catch up, and bask in this place of freewheeling creative genius. Who knew? Maybe the spirit would rub off. In the living room, Graham Nash had gifted the house a large print of a stark photo he’d taken of Neil Young driving off on a dirt road behind the wheel of a classic sports car. Bet and I slept upstairs, in drummer Levon Helm’s dormer. The basement had been restored to its original recording condition, where I sat in the chair still marked “Bob.”

Perhaps because of the pop poetry in the air, our talk that weekend turned to the phenomenon that is Taylor Swift. Naturally, I compared the moment, unfavorably, to the Dylan era, when cultural antiheroes reigned. That other poet of the 60s had said, “I don’t have to be what you want me to be” in reaction to the mainstream outrage when he’d changed his name from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali. So, too, did Dylan refuse scripted lines. Like Ali, Dylan played the role of trickster (“I see myself more as a song and dance man” he replied when a press conference interlocutor asked if he was poet or singer); he defied categorization.

“I just can’t have people sit around and make rules for me,” he told Nat Hentoff in the New Yorker nearly a year before the events chronicled in the biopic A Complete Unknown, when he “went electric” and essentially ended the folk music movement at the ’65 Newport Festival. In that Hentoff piece, Dylan signaled the revolution he would spark, referring to folk as “finger-pointing” songs: “I looked around and saw all these people pointing fingers at the bomb,” he said. “But the bomb is getting boring, because what’s wrong goes much deeper than the bomb. What’s wrong is how few people are free.”

Whether rock and roll would have become grown-up music anyway is an open question, but there’s no doubting the Dylan influence.

Swift, I argued, is commerce; Dylan was revolution. MacDonald, who is a spry 83, turns out to be a Dylanite and a full-on Swiftie. “She’s pretty amazing, actually,” he said. He made the case: If Dylan, as the biopic documents, was an artist always in a state of becoming, so, too, is Swift. Like Dylan, she has long refused to be pigeonholed by genre. Dylan, of course, was the ultimate rebel — the This Machine Kills Fascists sticker affixed to his guitar, the leather jacket, the motorcycle. He always seemed so … fearless, storming off the set of Ed Sullivan when the producers banned him from singing Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues.

Yet, In the documentary Miss Americana, we see Swift determined to publicly oppose her home state MAGA Senator Marsha Blackburn. And when her master recordings were sold to her arch enemy, Kanye West manager Scooter Braun, Swift pulls off a baller move, rerecording and rereleasing her entire back catalogue, album by album, in a move of both creative and commercial genius.

Moreover, she speaks teenager — particularly teen girl — in a way no one has, not even The Beatles. “They’re here to see Taylor sing her life, and hear their lives get sung,” writes Rolling Stone’s Rob Sheffield of her audience in Heartbreak is the National Anthem: How Taylor Swift Reinvented Pop Music, calling her concerts “tribal ritual celebrations.”

“Watch the video for I Can Do It With a Broken Heart,” MacDonald counseled me. “It’s all about still kicking ass professionally with a broken heart. The broken heart is a metaphor for handling loss of any kind, and it really spoke to me after the election. I find her really exciting and brave.” Which is exactly how a younger version of MacDonald felt when Dylan exploded pop consciousness. Just imagine how those teenagers, especially teenage girls, feel at the Swift communal gatherings? “I can’t wait till all these girls grow up and start bands of their own,” writes Sheffield.

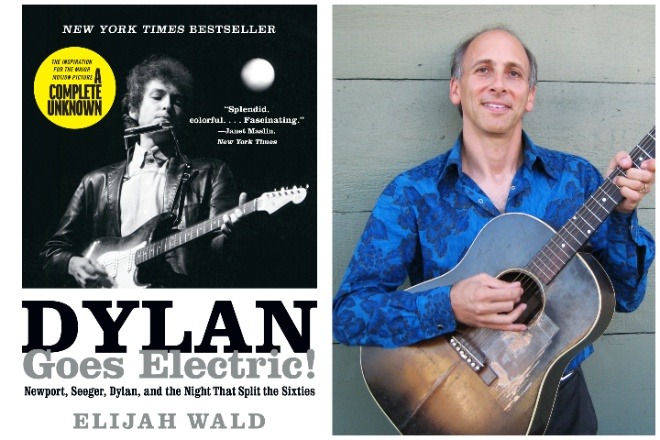

The Dylan / Swift debate was a running theme of our Woodstock weekend, and it all came back to me after seeing Timothy Chalamet’s stunning big-screen portrayal of the Bard. Turns out, the book that is the basis for the movie, Dylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties, was written by longtime music author and South Philly resident Elijah Wald. “Bob Dylan was busy being born, and anyone who did not welcome the change was busy dying,” Wald writes at one point in his meticulously nuanced narrative.

Who better to kick all this around with? Just before the movie came out, none other than the Bard himself tweeted a plug for it. It’s long been held that Dylan makes it a point not to read what’s written about him, but this tweet was evidence to the contrary:

Timmy’s a brilliant actor so I’m sure he’s going to be completely believable as me. Or a younger me. Or some other me. The film’s taken from Elijah Wald’s Dylan Goes Electric — a book that came out in 2015. It’s a fantastic retelling of events from the early 60s that led up to the fiasco at Newport. After you’ve seen the movie, read the book.

That’s where I began with Wald upon catching up with him last week. The following is an edited and condensed version of our conversation:

Larry Platt: So what was it like to get an endorsement of your book from Dylan himself? That’s quite a blurb.

Elijah Wald: I’m going to go with astonishing.

I’d always heard he’d never read anything written about him.

I’d heard that, too. His people optioned the book when it was published in 2015, so I’m guessing he read it then. But it was incredible. And it’s very funny because a certain number of people have leapt to my defense saying, No, read the book first, but I actually think he got it right. I think it works better. Go see the movie, get interested, then read the book and get the facts behind it.

Well, that’s what I did. I couldn’t stop thinking about the film and your book is so well-reported, it not only answered a lot of questions — it also told the true story without the understandable biopic conventions.

By the way, what’s your Philly story? I thought you were from Boston?

I was born in Cambridge, Boston, yeah. But I’ve lived a lot of places and have been here seven years.

What brought you to Philly?

Cost benefit analysis. It’s the best place to live in the United States right now. What we have here versus what it costs to have a place here, there’s nothing comparable.

That’s quite an endorsement. So, can you give us some context of what the real story is behind the night when Dylan went electric?

Well, what was important that night was the booing, in a historical context. He had already released two albums with electric tracks. The news was the reaction of the crowd. Yeah, the film blows that out of proportion. It is true that people booed, but how many is completely unknown and it’s never going to be answered. But the fact of the booing is what made that evening matter. If the narrative was simply, Dylan decided to be a pop star like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, that would be one thing. But the narrative instead was, Dylan decided to be an artist, like Stravinsky, who would go his own way, even if the public hated him.

Yes, he even tells the band to play louder when getting booed. There’s a great risk choosing to piss off your audience.

That’s the narrative, that the booing is proof that this was a brave artistic decision. But going electric was also a career move, whether he intended it that way or not. His first album didn’t make the charts at all. The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan went to number 22. Bringing It All Back Home was his first top 10 album and that’s because it had an electric single that was on the radio, Subterranean Homesick Blues.

Interesting. So big picture — what was really at play here? Why was the night Dylan went electric so important culturally?

I think what was really at play was rock music becoming the voice of a generation. And the idea that pop music was not just what kids danced to, that it was important and completely new. It was the idea that intelligent grownups who went to college would listen to pop music on the radio, rather than sneer at it. And let’s not leave race out of it. There are still people today who think that what Dylan did in the 60s was more forward looking and important than what James Brown did in the 60s. I think they are simply ignoring reality.

Elaborate on that.

There is a general perception among intelligent White people that the great modern artists of the 60s in terms of popular music were The Beatles and Dylan. Anybody who in fact looks at the history of popular music can see that the person who was looking towards the future was James Brown and that we’ve been living in the post-James Brown world ever since. I mean, you can argue that Dylan and The Beatles lead us to Taylor Swift. But James Brown leads us to first disco and then Hip Hop and now R&B.

I never thought of it like that. I read James McBride’s book on James Brown —

That’s a great book —

But I don’t remember coming away from it feeling like he was Dylanesque in terms of cultural influence, but when you lay it out like that, it’s pretty convincing.

There’s this term among pop critics and music people: “Rockist,” a critique of the charting of what’s important and intelligent music. You know, in the late 70s there was this line of thinking that would describe punk as the big thing that happened, like it was as important as disco, despite the fact that no one listened to it except a bunch of White boys.

Taylor Swift is a pop star. I mean, Taylor Swift is as big as The Beatles. Dylan was never anything resembling that big.

Interesting. That explains the slighting of James Brown, but Dylan was never accused of cultural appropriation, right?

In a sense, Dylan is the escape from the issue of cultural appropriation because he was framed in the standard historical narrative as a descendant of Woody Guthrie rather than as the new Elvis. Fact is, he was strongly influenced by Black musicians like Robert Johnson.

For me, compared to the film, you really paint a three-dimensional character in Pete Seeger. You say that the split between him and Dylan, the divide between folk and rock, represented Seeger’s communitarianism versus Dylan’s libertarianism.

For Seeger, Newport was about forming community. And so Dylan did destroy something that night, the idea that folk music was building a community that meant more than just the music. That this movement was going to change the world. You know, these were people who were all linking arms and singing We Shall Overcome and Blowin’ in the Wind. And Dylan was tired of being made the spokesman for that. He was saying, I’m not interested in being part of your club anymore.

But if you were there at that moment, it was complicated. Ever since that night, there has been a tendency to frame Pete Seeger as the old fuddy-duddy who didn’t get it. And quite a few people do feel like Ed Norton is a bit of that character in the film, and others feel like he comes off as very decent. Part of me wanted to rescue Pete Seeger in my book.

And then at the end of your book, Seeger looks back on it all and says “Maybe Bob Dylan will be like Picasso, surprising us every few years with a new period.” To me, that shows that he completely got it, in the end.

The interesting thing is, after Newport, Dylan released Blonde on Blonde and then he went back to making a folkie record just when everybody was saying, no, rock and roll is the next new thing. It was Sergeant Pepper’s and Blonde on Blonde, and what’s Dylan gonna do next? And what Dylan did next was make the most retro record in some ways of his entire career.

Was that John Wesley Harding?

Yeah. It was sort of, like, You think I’m now the standard bearer of the new rock and roll sound? No, sorry.

What was really at play was rock music becoming the voice of a generation. And the idea that pop music was not just what kids danced to, that it was important and completely new.

That said, Dylan did have a lasting rock influence after Newport, no?

Sure, just look at his imitators. I mean, the summer of ’65 Dylan is putting out Like a Rolling Stone and going electric at Newport. Well, The Rolling Stones’ number one record then is (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction, a Dylan imitation. And they follow it with Get Off of My Cloud, As Tears Go By, and 19th Nervous Breakdown. They’ve just gone full Dylan. And The Beatles were very clear about it. Lennon listed the songs he thought of as Dylan songs — Nowhere Man, Day Tripper. You know, these ain’t I Wanna Hold Your Hand.

Whether rock and roll would have become grown-up music anyway is an open question, but there’s no doubting the Dylan influence.

I wonder if you have thoughts on the Taylor Swift phenomenon — she’s very different from Dylan, of course, but there’s a familiar “voice of a generation” narrative going on.

The first thing I would say is, Dylan was not all that popular. I mean, Taylor Swift is incomprehensibly more popular than Dylan ever was. Let me ask you — what was Dylan’s first number one album? I’ll give you a hint. When they say at the end of the film that his new album, Highway 61, went to the top of the charts, it’s not true.

I’m tempted to say Blonde on Blonde, but the fact that you’re posing the question would mean it’s probably something later like, maybe Desire?

Actually, Desire was his third album to make number one — Planet Waves was his first. The first Dylan album to sell a million copies was Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits. He was a cult figure — a hugely influential cult figure. But Taylor Swift is a pop star. I mean, Taylor Swift is as big as The Beatles. Dylan was never anything resembling that big.

Pop music sales are very gendered. Simon & Garfunkel outsold Dylan and the Stones. Why? My sister bought Simon & Garfunkel; I bought Dylan and the Stones. And groups that appeal to girls have always sold more.

I would also say that Taylor Swift came in as the lonely girl who’s sitting in her room writing poetry. A lot of people, particularly a lot of males, didn’t become conscious of her until Kanye West dissed her at the MTV Video Music Awards and many felt like, yeah, I get what he’s saying. Like, it should obviously be Beyoncé who wins this award, not this cute blonde. But if you were actually paying attention to her stuff, it was very feisty. Her stuff was very, I’m not gonna take it anymore. That girls need to stand up for themselves. In that way, she wasn’t Justin Bieber, she was as much of a counterculture figure as a Joan Baez.

In what way do you make the Baez connection?

Baez was also the lonely girl. She was not the cheerleader. She was an idol for the young women who were not cheerleaders and who despised the cheerleaders.

What about the fact that Dylan became one of many antiheroes — Ali, Abbie Hoffman, I don’t know, maybe Gloria Steinem — who changed the culture. That seems gone now, the idea of the power of the nonconformist willing to suffer on principle for some higher ideal?

There are a bunch of different possible answers for that. I mean, the Vietnam War made outlaws a lot more popular. But the other thing I’ll say is that the outlaw mystique is still very much alive, but right now it’s more dominant on the right than on the left.

Oh, yeah, I guess so. Our anti-heroes today are Joe Rogan, Elon Musk and RFK, Jr.?

Or Ted Nugent. Think about the storming of the Capitol. It’s hard to imagine more of a rebellion without a cause. I mean, if you had asked the people storming the Capitol what they wanted to build when they’d torn it down, I doubt more than a fraction of them would have had the faintest idea. So the Rebel Without a Cause mystique is still very alive. We just don’t like the people who are over there right now.

That’s a fitting place to end — on the discomfiting notion that the right has co-opted the spirit of cool rebellion. Thank you for this book, and your most recent one, Jelly Roll Blues: Censored Songs and Hidden Histories.

Thank you.

Correction: This has been corrected to note that Dylan’s first album only did not make the charts.

![]() MORE MUSICAL STORIES FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE MUSICAL STORIES FROM THE CITIZEN

Tmothée Chalamet in A COMPLETE UNKNOWN. Photo by Macall Polay, Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2024 Searchlight Pictures All Rights Reserved.