To this story in CitizenCastLISTEN

“I’m worried about seven or eight people all thinking about running for mayor at a much earlier time than ever before,” he said, “when we need to put politics aside and come together to face about four major crises that are all happening at the same time.”

The former governor—our legendary mayor in the ’90s—went on to note that he didn’t necessarily disagree with everything I’d written, but he’d lately grown tired of the city’s all-critique, no-solution narrative. He’d been paying attention to my criticisms of Jim Kenney, he said.

“I’m not saying you’re being unfair to Jim—all mayors are properly subject to criticism,” Rendell said. “But we only have one mayor. Our job is to help him be better.”

I believe if business leaders, political leaders and media leaders like you went to the mayor and said “C’mon man, we’re dying for leadership, you can do this, and we’ll help,” I just know he’d react very well.

I couldn’t agree more. The Citizen’s founding ethos is to focus on solutions, and even in the most pointed pieces on Mayor Kenney, I’ve taken pains to suggest constructive policies. But the truth is that I’ve grown tired of writing about Kenney administration missteps and would like nothing better than to help change the narrative.

“Well, [Congressman] Dwight [Evans] and I have been talking,” Rendell said. “We’re both concerned about the state of things.” He suggested the three of us have a conversation as to how we can get to a better place, civically.

Isn’t it funny how much smarter your parents get the older you become? At various points 25 or 15 or 10 years ago, I’d complained publicly about both Rendell and Evans, but even then I always marveled at their political skills and vision.

For context, let’s reintroduce them. In 1992, Rendell took over a Philadelphia that would hardly be recognizable today. The city was near bankruptcy, 500 murdered bodies dotted our landscape (rivaling today’s depressing murder rate), and 3,000 jobs a month were disappearing or leaving the city limits.

Come 5pm, the city would essentially shut down and turn into a ghost town after dark. (A Rendell-inspired program that kept retail outlets open until 8pm on Wednesday nights keyed a slow rebirth of nightlife). Within four years, through his indefatigable optimism and energy, Rendell had lifted the city’s spirits and put it on a trajectory of growth.

At the same time, Dwight Evans had become an important legislative partner for the city in state government, the longtime head of the House Appropriations Committee. Now a congressman, Evans has, more than most pols, been willing to deviate from ideological orthodoxy in pursuit of the common good.

Both men have embraced innovation in their public lives. I think I’ve learned more about the art of dealmaking and leadership from watching Rendell than any pol on earth. And Evans—as documented in his 2013 book, Making Ideas Matter: My Life as a Policy Entrepreneur—has long been a deep public sector thinker.

So I jumped at this chance to talk with two giants of Philadelphia politics. After some obligatory Eagles talk with Rendell, we got to it. What follows is an edited and condensed transcript of our conversation.

Larry Platt: First, let me say how cool it is that you both wanted to have this conversation. I’m also concerned about the state of the city and want to be as constructive as possible.

Ed Rendell: Thanks, Larry. Let me start, and then Dwight can weigh in and you can ask questions. As a citizen, not as former mayor or governor, I am increasingly concerned about the challenges facing Philadelphia—all at one time. The pandemic, the economy, the racial awakening, the murder numbers —each one would be difficult to deal with on their own. Jim Kenney didn’t cause any of these and yet he has had to deal with them all at the same time. No mayor, myself included, has had to deal with such gut-wrenching problems all at once. But my concern is that the response to them has been more finger-pointing than a constructive banding together.

When I took over the city, we had the largest deficit in our history and were losing 3,000 jobs a month. There were lots of problems, but the political class, the business community and the media to a certain extent all banded together to face a crisis together. And as a result we were able to do things that under normal circumstances we’d never have been able to do, like privatizing services. Once we chose a private, low-bid company, city workers were given the chance to meet the bid. We ended up privatizing 42 different things, all of which required approval from City Council.

The municipal unions would pack Council’s gallery, shouting and carrying on. But we never lost a vote. That was because of two things: The leadership of John Street, the best Council president in our history, who realized what the city was up against, and the fact that the public had let officials know that they wanted change. City government acted as a cohesive unit. We gave Harrisburg the message that we’re going to get our house in order before we come to you.

Look, Jim Kenney has made mistakes, sure, but so did I and so did every mayor the city has ever had. He gets criticized, sometimes rightly, but he gets no credit for what he’s done. His pre-K and Rebuild programs were good accomplishments, the benefits of which the city will be realizing for years to come. On the pandemic, did you know that of the biggest 9 cities in America, we have the lowest daily case rate, tied with D.C.?

The British are at 19th and Market. We’re in crisis. We’ve got to rally around the flag.

Jim Kenney should be praised for this. On the lockdown, he took some difficult steps. Restaurants, gyms and retail stores were pissed off, but he made the right decision from a public safety perspective. It took guts. Had I done something like that, there would have been editorials about how courageous I was.

Look, Jim’s a terrible self-promoter, but given the lack of support he’s gotten from City Council, he’s been unfairly targeted as the sole cause of our problems. If I could make one plea to elected officials and the business community, it would be to get together. We only have one mayor and Jim Kenney will be ours for the next three years.

Dwight Evans: Larry, when Ed asked if I’d have this conversation, I said yes immediately. I was born in this city: North Central Philly to Germantown to West Oak Lane. I love this city. And for all our challenges, we’re still the best city in America.

But Ed laid it out. You’re always going to have second-guessers. There’s no single person who can deal with all the problems Ed just mentioned. We have to come together to figure things out. You know who gets that? Our president. He knows that people don’t care about political sideshows. It’s all about delivering for the people, which we just did with a $1.9 trillion—that’s trillion with a ’T’—relief package.

LP: It does seem like there’s more of a leadership vacuum now—at least at the local level. As you said, Guv, when you were mayor, you weren’t the only player making change.

ER: There was a strong business community, with guys like Ron Rubin, who was powerful. I’d say to the business community today to get off your high horse, get involved, and write checks to make the city better.

And remember, in Harrisburg, I had Dwight and [State Senator] Vince [Fumo]. Jim doesn’t have that. You know, the other thing I’d say on leadership is that different leaders respond differently to criticism and praise. It’s like with children—some respond well to criticism and change their pattern of behavior. Some kids need praise.

The same can apply to leaders. I believe if business leaders, political leaders and media leaders like you went to the mayor—I know that he considers you a nemesis, Larry—but if you and others went to him and said “C’mon man, we’re dying for leadership, you can do this, and we’ll help,” I just know he’d react very well.

DE: You know, when I got to D.C., I had the pleasure of meeting and serving with John Lewis. Now, Ed talks about media leadership. The first time I saw John Lewis, I was 10 years old and Walter Cronkite was showing the world John Lewis crossing that Pettus Bridge in Selma. People today don’t know—Walter Cronkite was America’s trusted voice. Locally, we had John Facenda—that trusted voice.

That doesn’t exist anymore. You guys in the media, your numbers in terms of trust are below ours in Congress—that’s saying something. There are no more Walter Cronkites, we have to make due with the Larry Platts…

No mayor, myself included, has had to deal with such gut-wrenching problems all at once. But my concern is that the response to them has been more finger-pointing than a constructive banding together.

LP: We are so screwed—

DE: But my point is it’s up to us now. It’s up to each citizen to lead, because there are so few trusted sources anymore.

LP: I’m totally with you guys that media should be part of the solution, instead of just providing more noise. That’s part of the Citizen ethos. But civic discourse and community has broken down all around us—how do we get it back?

ER: When I was mayor, I cut $250 million out of the budget with the promise that we’d make it up to city workers, and we did so in four years. But it was the media that held me accountable to that. And I think there are things going on right now that are a step in the right direction, but those stories aren’t being told as much. Have you seen what Sue Jacobson and The Chamber have put out, about building the economy back?

LP: Yes, we’ve covered it.

ER: That’s a step in the right direction.

LP: But then you get a blizzard of stories about the administration turning the vaccination rollout over to a group of 22-year-old college kids and you wonder if trust in government is even possible.

ER: That was hard to understand, I grant you—

DE: Yes, but at the same time, look at what the Black Doctors Covid Consortium has done. I know Dr. Ala Stanford, I knew her mother, I knew her grandmother. They’re doing this around the clock, 24 hours a day. They have a model and they have community trust. We should be hyping that.

LP: Makes you wonder why the city didn’t just hand the whole operation over to her.

DE: That’s what Ed Rendell would have done.

ER: Another thing that worked: Restaurants have been suffering badly. Jim allowed for streets to be closed so there could be more outside dining. A lot of restaurants survived and even thrived on that. Jim got that done but he got no credit for it. We need more innovative solutions like that.

LP: It does feel like we need a win on the board. What could that be?

ER: I think we have a chance with the Biden administration, which will be city-friendly, and with Dwight and me and our relationships, there will be significant help from infrastructure to tourism.

DE: Philly has what it’s never had before—two members on Congress’ Ways and Means Committee. We just passed a $1.9 trillion relief package with housing money, with small business money. Help is on the way.

LP: Of all the long-term challenges we face, I almost think the most pressing ought to be the fact that we’re a city that is 45 percent Black and only 2.5 percent of our businesses with employees on payroll are Black-owned. I’m with Obama, who said that the best anti-poverty program is a job. So how do we actually get capital to African-American entrepreneurs?

DE: No one has worked on this longer than me. Small business was the first committee I worked on. The $2.2 trillion CARES Act was targeted to small businesses. We funded CDFIs—[late founding Citizen chairman] Jeremy Nowak would have loved that, he was a CDFI. Between that and this relief bill and what’s still to come, we’re really talked about enacting a Marshall Plan for cities. You’re right, we need to do more. But look at Della Clark—she’s doing it. She’s singularly focused on Black business development. Biden just announced a two week window for Black-owned businesses to apply for PPP loans, so it’s changing. We’ve only had the presidency for a little over a month.

ER: What you have to do is get all the major banks in a meeting with the Small Business Administration office, with representatives of the federal and state governments, and you say, “We’ve got to get more capital to Black businesses. But I’m not asking you, Mr. Banker, to take on more risk.” Instead, you work out a deal where the feds and the state guarantee a percentage of the loans. A $50,000 loan to a corner barber shop may be too risky, but not if three-quarters of it was backstopped by a combination of the federal and state governments. And our past experience shows that the vast majority of those loans will never be defaulted on.

LP: That’s a great illustration of political leadership. Locking parties in a room and saying you’re not leaving till we get a deal. You both are consummate dealmakers. It may be ugly sometimes, but it seems to me that that’s how you get things done for the people. Governor, I’ve often cited the deal you made with Republicans in your first gubernatorial budget, that you wouldn’t campaign against them if they voted for $300 million in new school spending—

Look, Jim Kenney has made mistakes, sure, but so did I and so did every mayor the city has ever had. He gets criticized, sometimes rightly, but he gets no credit for what he’s done.

ER: I wrote them a letter of praise that they could use in their advertising if they were attacked for voting for a tax increase!

LP: And Congressman, there’s an anecdote in your book about how you secured a $500,000 appropriation for some statue in the middle of the state because you needed a tax vote that would be critical for Philly—

DE: The George Marshall statue in Uniontown! I’ll give you another example, the Fresh Food Financing Initiative—

LP: A public/private partnership that brought fresh food stores into food deserts …

DE: An innovative program, very practical, with tangible results. That wouldn’t have happened without Ed Rendell in the governor’s office.

ER: That’s kind of you to say, but remember, I had John Street in Council, you and Vince in Harrisburg, and Bill Gray in Washington. This is what I’m trying to say, Larry. You have to have somebody to make a deal with, and Jim doesn’t have that.

LP: Let me ask you guys about crime. I remember when murders were running rampant in the ‘90s, and you both spent considerable political capital to turn that around.

ER: Let me tell you how that went. I thought we just needed more police, and I pushed the Clinton administration for the crime bill, which added about 1,000 more cops. But it didn’t do much. Dwight called and said, “We’ve gotta do what New York did with its Broken Windows policing.” Dwight convinced me, and we brought [former NYC police commissioner] Bill Bratton in to consult. I said to him, the theory makes sense—who could implement it? He mentioned John Timoney [who went on to become Philadelphia Police Commissioner], who Giuliani had gotten rid of.

You can disagree with the policy, but the point was, this wasn’t my idea—Dwight came to me with that idea. You can’t get stuck on pride of authorship in this business.

DE: And those decisions were made in partnership with the community. You’ve got to have community trust, which Ed worked at.

There are so many common sense reforms that add up to real money in the budget, but no one has bothered to look for them in decades. You’re going to piss some people off, but you have to withstand that.

LP: We may be heading for another hit to the city budget, as high as $450 million—

ER: The federal money we get might lower that.

LP: Right, but I’m wondering if you have advice for the mayor as to how to handle yet another budget hole?

ER: You’ve got to go back to some big ideas. Reduce costs, reform overtime. Manage benefits, reform work rules. There are so many common sense reforms that add up to real money in the budget, but no one has bothered to look for them in decades. You’re going to piss some people off, but you have to withstand that. You can’t cut services any deeper.

LP: You know, governor, you talk about being willing to piss people off. You both have stood up to your supporters. Governor, I remember when you, as mayor, brought in Rev. Louis Farrakhan to help quell racial unrest—

ER: The Jewish leaders killed me!

LP: And Congressman, you’ve angered Democrats by working with Republicans, and teacher unions were upset when you supported charter schools. Is it me, or is there not a lot of that kind of spending of political capital going on nowadays? It seems like no one wants to tell their supporters anything they don’t want to hear.

DE: It’s very simple. It has to come down to, will this help the people who sent me here, or not? That’s it.

ER: Politics today have become incredibly wussified, even worse than when I wrote my book. A Nation of Wusses: How America’s Leaders Lost the Guts to Make Us Great. People aren’t willing to do things that might be temporarily unpopular but are the right thing to do for the long-run benefit. I think Jim has shown some willingness to take those risks. So if we do rally around him, I think not only will he respond, he might just give us the leadership we need.

I want to close by coming back to why I called you, Larry. The British are at 19th and Market. We’re in crisis. We’ve got to rally around the flag.

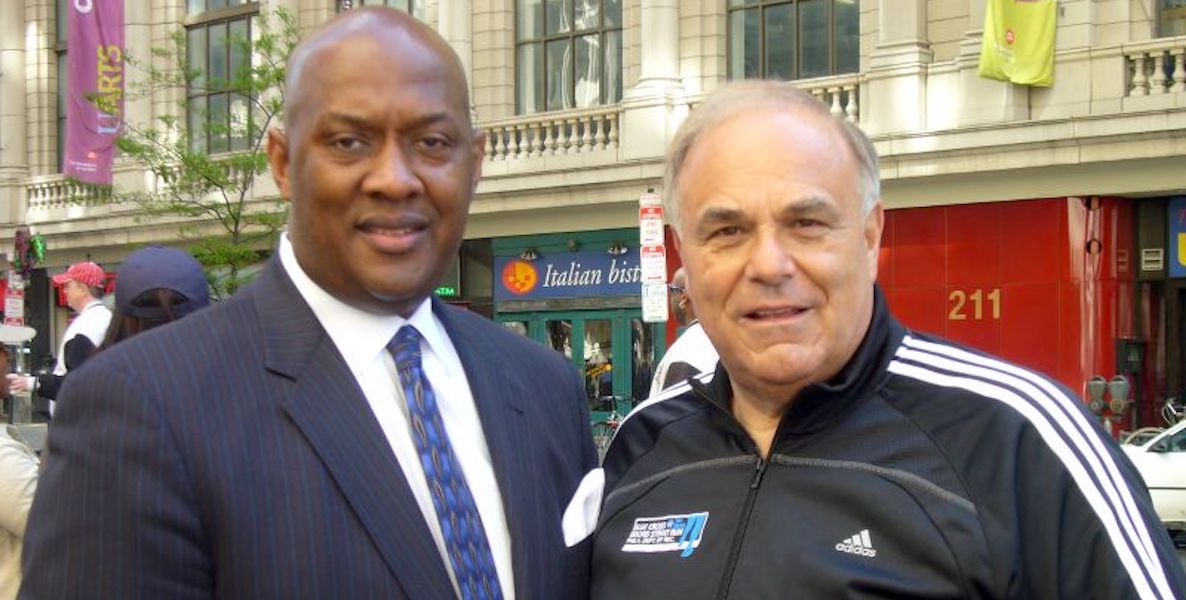

Header photo by Dwight Evans / Flickr