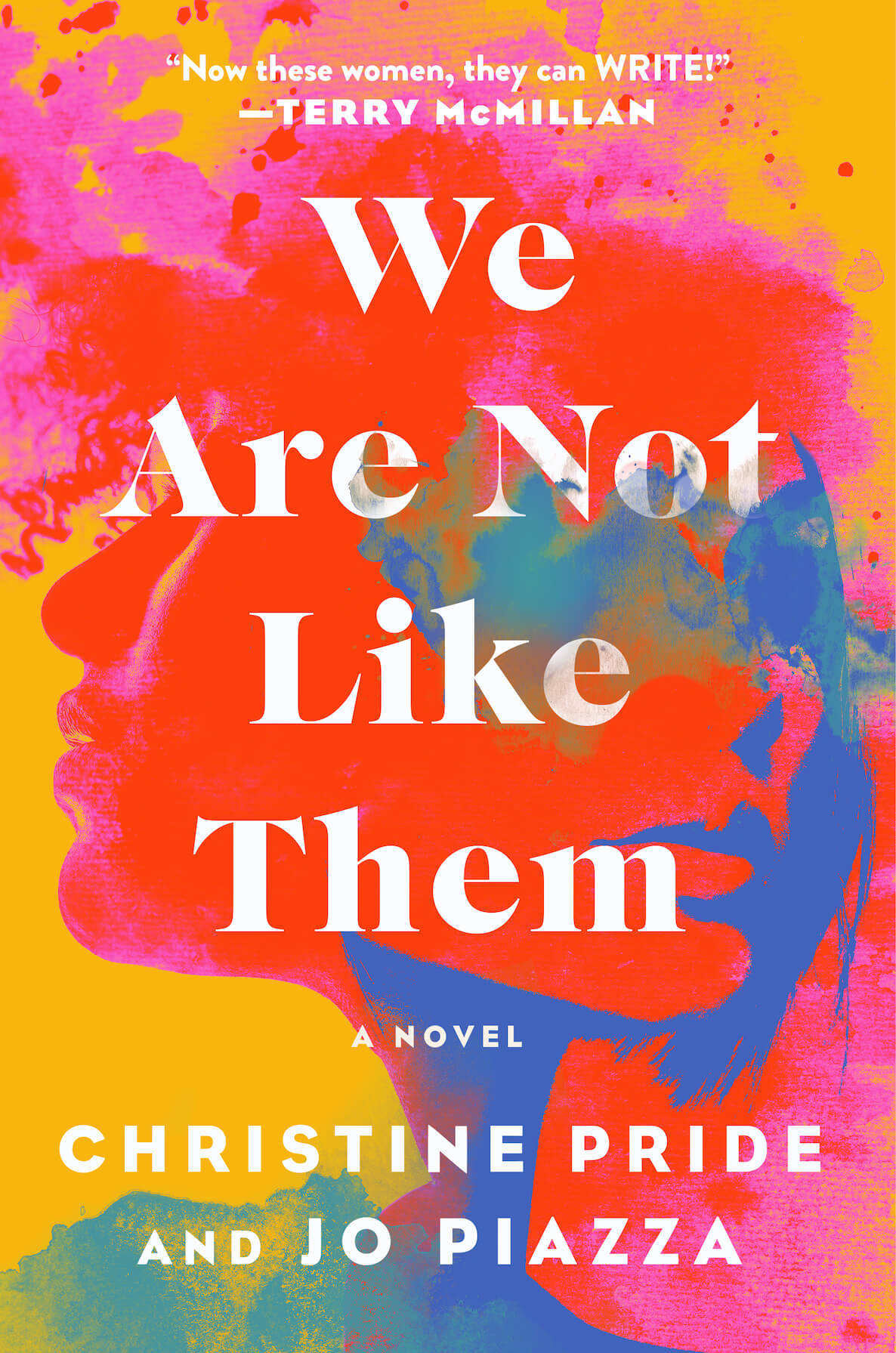

When authors Jo Piazza and Christine Pride first pitched their new novel—about two women’s lifelong friendship that is tested by a police shooting of a Black teenager—to publishers back in 2018, they found themselves facing, what to them, was unexpected push back.

Despite the fact that nearly 1,000 people were shot by police in 2018, their pitch landed in what publishers were calling a “lull” in shootings.

“They’d say, Is this even going to be an issue when we publish this book?” says Piazza, who also reported and produced Philly Under Fire, The Citizen’s podcast investigating the gun violence epidemic in 2020. “Christine and I were like, Yup. The world has been in the thick of this; our country has been in the thick of this; all that’s changed is who is paying attention to it. So many people think we came up with this idea with the murder of George Floyd. But no, this has been happening all along—and it will continue to happen.”

RELATED: Philly Under Fire Episode 1: “Roadmap to Nowhere”

Piazza, a journalist, podcaster and author, and Pride, a book editor, first met when they worked on Piazza’s 2018 book Charlotte Walsh Likes to Win. They finished co-writing We Are Not Like Them in 2019, with plans to publish in 2020. Then George Floyd was murdered by a Minneapolis police officer, sparking much-needed outrage and a new sort of racial reckoning across the country. So they went back in and slightly revised the story. The updated novel comes out today.

The book, set in 2019, relates a year in the life of Jen, a White woman, and Riley, a Black woman, who have been friends since they first met as young children in Northeast Philly. By the beginning of the second chapter we are introduced to the primary action of the novel: Jen’s husband, Kevin, a Philly cop, shoots an unarmed Black teenager; Riley, a TV journalist with her eye on the anchor’s seat, is the lead reporter covering the incident.

The book, set in 2019, relates a year in the life of Jen, a White woman, and Riley, a Black woman, who have been friends since they first met as young children in Northeast Philly. By the beginning of the second chapter we are introduced to the primary action of the novel: Jen’s husband, Kevin, a Philly cop, shoots an unarmed Black teenager; Riley, a TV journalist with her eye on the anchor’s seat, is the lead reporter covering the incident.

The primary tension of the book, though, is the relationship between Jen and Riley, and whether their lifelong friendship can survive their new reckonings on race, motherhood, geographic distance, adulthood and the changes that brings.

I spoke to Pride (who is Black) and Piazza (who is White) a few days before the book’s release. Here’s a condensed and edited version of our conversation.

Roxanne Patel Shepelavy: First of all, how do you co-write a book?

Jo Piazza: It was hard, for three years—it’s hard to figure out what a process feels like. Writing a book is hard, generally, and takes training and habit and also a little bit of fairy dust. There has to be something magical involved.

To co-write, I first had to get Christine to use Google docs. Publishing hates technology. They’re like, Why can’t we always use Microsoft Word? And frankly I think they’re pissed that we don’t use typewriters anymore.

We came up with an outline together. In the very beginning, because I’d written a lot of books and Christine is an editor, we defaulted to those roles. I would write a chapter; she would edit. Sometimes she’d tear it up and do it all over, but the blank page is terrifying. But then, we both just started writing things as they hit us—we’d be running, or in the shower, or at 3 in the morning. We’d text each other with an idea and then go for it.

It was completely collaborative—one would write a chapter, the other would go in. We’d just keep going, layering on top of each other until we were done.

RPS: You finished writing the book in April 2020. And then, of course, George Floyd was murdered. How did that change the book?

Christine Pride: We were done, and the world changed. We had done a ton of research along the way about indictments and convictions [of police officers]. We all knew, it wasn’t surprising, the statistics were dismal about there being any consequences, even losing your job, for police officers. Our original version reflected that reality.

When the zeitgeist changed—it wasn’t that those statistics changed—the public thirst for justice and to feel like there’s a real resolution changed. We lost our appetite in the best possible way for letting these things slide. We responded to that.

I think that’s one of the things our book really interrogates: What is justice, what is going to make something right that you can’t make right? How do you balance these things? What is forgiveness? We wrestled with that and made some tweaks accordingly.

But we wanted to keep it set in 2019. There’s something interesting about things happening in the “before”. Readers now, what feels like years later, can have conversations about that juxtaposition. In all my years as an editor, it’s never been the case that you could write a book in say, 2017, and publish in 2018, and have the world be so different.

RPS: One thing that really struck me was the time spent with [Jen’s husband, the police officer] Kevin and his family. You brought understanding and empathy for the police in a shooting, which was different.

CP: We didn’t want to write a morality tale. It would be easy for us to have a one-dimensional story, to have a hero and a villain. We didn’t want to do that. And we might get some flack for that—in our polarized society, it’s a little bit all or nothing.

“One of our main characters is a police wife: What is that world like? What is it like to have the father of your child be a murderer? That’s fascinating.”

Some people don’t appreciate nuance. They are not going to appreciate the nuance we brought to the table.

JP: I remember early on, someone read this and said, Screw the police. That’s not what we’re doing here; our goal is showing these shades of gray.

We talked to a lot of cops, and their wives—and to a lot of Philly cops. Philly is its own beast; it was so important to make sure we got Philly right, I know Philly will come after you if you don’t. I didn’t realize how close-knit the police wife community was and how much of an ID being a police wife and family is. I think we would have done a huge disservice to readers if we hadn’t taken the extra time with our cop character and his wife because we’re not here to preach, we’re here to get people thinking about who they are. We wanted to show the humanity and the real people behind the headlines.

One of our main characters is a police wife: What is that world like? What is it like to have the father of your child be a murderer? That’s fascinating.

CP: People assume we came to this book with an agenda. We just wanted to tell a good story.

Our focus in this book, even though it’s animated by a police shooting, has always been on the friendship, the relationship between these two women. There is some tension around how these incidents are going to affect their lives that we hope people are invested in. But what we really want is for people to be invested in their relationship, and will they come together in the end, even if they had differences around race, motherhood, long distance, whatever the issues are.

We did that by blending the experiences and perspectives, and telling the story from our two different experiences and different conversations we overhear and participate in. Jo is privy to conversations I am not, and vice versa. We could bring that to the table.

RPS: There’s something kind of sneaky about writing about these issues of race and police violence in a book that is “chick-lit.”

JP: We wanted this book to be a novel, not nonfiction—very commercial, not high literary. We want everyone to feel really comfortable picking this book up and reading it with their book club or on a beach vacation, or on a plane.

We want you to enjoy this story—that’s why friendship and the plot was so important to us.

We believe in the power of stories to change people’s hearts and minds.

I got a text from someone who lives in New England, who’s very working class. The text just said, “I’m changed. Thank you.”

RPS: Obviously this book is targeted at women. But have you had any reactions from men?

CP: We were on a panel at a Heineken event; it was Jo and I, an older White guy and a younger Black guy. There were racial differences and age differences, geographical differences—the White guy grew up in the south, had a thick Alabama accent.

They were both really really touched by the book in a way that I’ve never seen in all my years as an editor, men talking this way about a novel targeted at women. They were both really surprised. The older White guy was crying at the end when he read the epilogue [from the perspective of the victim’s mother].

Our focus in this book, even though it’s animated by a police shooting, has always been on the friendship, the relationship between these two women. What we really want is for people to be invested in their relationship, and will they come together in the end.

They both picked up on different things. It seemed genuine to them because it dovetailed with their personal experiences in a way that we want this to. The older White guy talked about being in school in Alabama, 10 years after Brown [vs. Board of Education], what that looked like, to have integrated schools and maybe a chance for friendships, in the context of sports. It brought back a lot of memories for him.

The Black guy talked about how his sister actually is a journalist, and all the racist vile shit she gets in comments, which is such a horrible thing for Black journalists, politicians, anyone in the public eye. He’d really seen his sister go through that.

JP: At the end, the White guy said he’s going to give the book to his best friend and they’re going to have a little book club and talk about it. Especially since men read less fiction than women, we were so delighted that it touched him like this, and would love to bring more men on board.

RPS: Jo, you spent 2020 looking at the causes of, solutions to and consequences of gun violence for Philly Under Fire, the podcast you did for The Citizen. In the process, you interviewed so many mothers who lost their children to gun violence…

JP: So, so many…

RPS: Was there anything in the reporting that influenced the revision of the book?

JP: I was working on our podcast concurrently with when we were revising. Every time I did an interview I would text Christine and say, oh my god, I have to tell you this, or you have to listen to this audio.

The epilogue was one of the last things we wrote. We’d always toyed around with it, but it really came to us because we thought the mother and Justin, the victim, both deserve to end this story. One of the things I discovered reporting the podcast is that so often the victims in police shootings, and shootings in general, when they are young Black men, are an afterthought. We didn’t want Justin or his mother or their family to feel like an afterthought, or a device. We wanted this to feel like this was their story, too.

My reporting for Philly Under Fire helped me add such a depth to the character and the character’s family that I think I wouldn’t have had otherwise.

RPS: Do you have relationships like Riley and Jen in the book?

CP: I grew up in a fairly diverse suburb—it got more diverse over time. My parents bought the house I grew up in in a new subdivision in Maryland, in Silver Springs, which is now touted as a suburban racial utopia: A story in the Washington Post showed stats that said outcomes for Black men growing up in suburban Maryland are the best outcomes for Black men in America.

When my parents found the house, they wanted to put an offer in—the realtors kept taking the listing down and wouldn’t let them buy the house. They ended up suing through the Justice Department and the Fair Housing Act to be able to buy this house. So we were the first Black family to move into the subdivision. That was in 1975 a few months before I was born.

The best thing Christine said to me is “your reaction matters more than anything when we start having these conversations. I don’t want to be afraid that you’re going to react badly to this conversation because that just puts more of a burden on me, so how can we get through this?”

The school system slowly changed—my elementary school was mostly white, was more integrated when I was in high school. One of my best friends, Julie, who’s White, I met in first grade; and Becky, I met when I was 14, in high school. I’ve had these close relationships with these two White women and others through my whole life. We’ve always talked about race, my parents are activists. Talking about race is such an integral part of my life.

In a way Jo’s and my relationship more so mirrors the relationship of Riley and Jen—they’ve never talked about race because they met before they were thinking about race. Jo and I were new friends, but we had never talked about race, and thrust into talking about race, which for me just happens in the normal course of the day. Jo had a different experience, and that was part of our early growing pains and friction.

JP: I grew up in Bucks County in a suburb that was very, very white. My wide social circle is very diverse; I do not have any close Black friends who are my very close friends. For me, I have not had to talk about race on a personal level.

So I had to learn how to have those conversations, how to be comfortable having them, and how to be comfortable with being uncomfortable. I can have them on a professional level, but when having them on a personal level I think a lot of white people do tense up and get worried about saying the wrong thing, or being insulting, and that presents as defensiveness which shuts down any conversation.

The best thing Christine said to me is “your reaction matters more than anything when we start having these conversations. I don’t want to be afraid that you’re going to react badly to this conversation because that just puts more of a burden on me, so how can we get through this?”

As our personal relationship was developing and our conversations about race were developing, so were our characters’ conversations. It was happening in real time for us; it then happens on the page; then what we’re hoping is that the readers will see those conversations on the page and think, now I have the language to go back and have those conversations too. We’re hoping it’s this big circle that will help people start talking more and making different and diverse friendships and be less afraid to have those conversations.

RPS: That’s beautiful. Thank you for writing the book—I hope it does well.

CP: We do too, Roxanne. We do too.

Jo Piazza spent a year reporting on Philadelphia’s gun violence epidemic—its roots, its victims, its toll on our communities—and the solutions that could be effective in curbing it. Listen to the resulting Citizen podcast, Philly Under Fire.

Header photo: Authors Christina Pride (L) and Jo Piazza | Photo by Julia Discenza