Last spring, a group of students was laying the foundation for a multi-generational garden behind Horace Furness High School. The students, members of youth programs at VietLead, met with their elders in the community to map out the garden. They got Furness principal Daniel Peou on board—eating lunch in a vibrant green space would be a good-behavior incentive for students, and growing food would get more parents involved at the school, he thought. They were all set to break ground.

Then, they found lead paint on the staircase above where they’d imagined water spinach, lemon grass, and bitter melon would grow. And everything came to a halt.

It’s not surprising: Horace Furness High School is among 46 school buildings the School District of Philadelphia has identified as “high-need” for lead paint stabilization. But it was a tough moment for the students. “The people who attended [planning meetings] were full of energy and happy and wanted to build this,” says VietLead student leader Tommy Ngeth. “And that made me happy—seeing people with shared goals. Seeing all of that go away really sucked.”

But it didn’t take long for these youth leaders from VietLead, a grassroots organization that builds self-determination among Vietnamese communities, to shift from one community improvement project to another. They calculated that it would cost $130,000 to repair and repaint the staircases and fire escape behind Furness, and set out to get the money from the School District. They reached out to their councilperson, Mark Squilla, and testified before City Council at the end of the school year. Then, in August, eight VietLead students took their story to the School Board, which unanimously approved the $130,000 project to be completed over the coming year.

“That made me happy—seeing people with shared goals,” says VietLead student leader Tommy Ngeth. “Seeing all of that go away really sucked.”

The victory was huge for the students. But cleaning the lead from Furness was no longer the end goal. Over months of research and testifying, the students had learned that schools across the city are suffering from the same unsafe conditions. And now they are determined to make sure other students join them in demanding change.

“We wanted to raise awareness and let the School District know it’s an issue, and send the message that it’s safer to learn outside than inside the building,” Furness senior and VietLead member Van Long told me through a translator.

Support Philly schoolsDo Something

Last May’s Toxic City: Sick Schools exposé in philly.com revealed the widespread contamination of city schools with asbestos, lead, bacteria and other asthma triggers, something the School District has said will cost $5 billion to fully repair. So far, the District has completed lead paint stabilization in eight elementary schools, has ongoing projects in 10, and plans to complete 30 schools by the end of the summer. (It’s prioritizing schools that serve younger children because lead has the potential to harm them the most.) In June, Governor Wolf pledged $15.7 million in emergency funds to start the cleanup, and last month announced plans to send another $100 million to the city if the legislature agrees to pass a modest natural gas severance tax.

“We don’t have the power to raise our own revenue,” says School District spokesperson, Lee Whack. “We rely on funding from the city, state and federal government.”

Meanwhile, the students at Furness have taken it on themselves to explain what all that means in real life. Last spring, Long—who enrolled at Furness when she moved to Philadelphia from a rural part of South Vietnam where her family farmed for a living—helped organize a Toxic Teach Out, a forum held outside Furness to discuss unsafe conditions in schools across the city and build garden beds in front of the school.

“It’s only right that people should know what’s happening within the area they live, and what they’re sending their kids out to,” Ngeth says.

They shared the stats: From 2015 to 2018 there were 49 lead paint reports, one asbestos damage report, 14 asthma reports, and five lead in drinking water reports at Furness. And one teacher told a story of being poisoned by lead in the water 14 years ago. “I learned how long Furness has had these issues and how little attention they get,” Long says.

Now VietLead is seeking funding for the repair projects in a different way: their new campaign calls on the city to end the 10-year tax abatement, enacted in 2000 to incentivize development in the city by waving taxes on an increase in the value of any property in Philadelphia for 10 years. According to a study released by Good Jobs First late last year, the School District of Philadelphia “lost” $62 million in 2017 due to abatements and other tax breaks.

The issue is more complicated than that, of course. A report by Drexel University’s Kevin Gillen shows the abatement has led to unprecedented growth, and that expired abatements have started bringing in increasing amounts of revenue each year, on properties that are high value. According to a study by City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart last spring, 59 percent of benefits for active abatements go to 6 percent of Philadelphia neighborhoods, like Center City, Graduate Hospital, and Northern Liberties. She offered several scenarios that could bring in more revenue to schools while still encouraging development, and City Council is considering ways to reform the abatement this year.

About tax abatements in PhillyRead More

For the students, though, the issue is not just about the income stream. It’s engaging their communities to get involved in making sure local officials hear them, and their concerns. At their annual Têt (Lunar New Year) Festival last month, more than 200 people milled around the Furness gym. Paper lanterns were strung above vendors selling bubble tea, rice paper salad, and skewered fish balls. Huge banners hung on the walls of the gym with the messages #StopHoggingStartFunding, #Coins4Communities and #TaxAbatmentIsTheft.

It’s the year of the pig and VietLead’s message is clear: more fair distribution of resources, please. “We’re really trying to come up with creative ways to educate our communities about issues we should be concerned about,” says Nancy Nguyen, VietLead’s Executive Director. In 2018, they designed education around the Know Your Rights campaign; this year, they raised awareness about their healthy schools and communities initiative with Toxic Tours and pledge cards.

About Philadelphia schoolsRead Even More

Tommy Ngeth and Van Long told the story of the garden from the stage at the festival. To them, getting the message out is particularly important. “Within our community, not everyone is told information that’s important, or they don’t have access to it,” says Ngeth. “It’s only right that they should know what’s happening within the area they live, and what they’re sending their kids out to.”

They’re hoping to spur more civic engagement within their community as well. Vietlead recently joined more than 30 organizations in support of the People’s Platform for a Just Philadelphia. Their student leaders are advocating for investment in healthy schools, ending the tax-abatement, and increased community control of land leading up to City Council elections this fall.

It’s not where Dinh imagined the group would be just a year ago, back when the students were planning the garden at Furness. “That is a reminder to me that as a jaded adult, I could think that [healthy schools] was too big of an issue to take on,” she says. But, like the students proved at Furness, if they believe they can win, they can win.

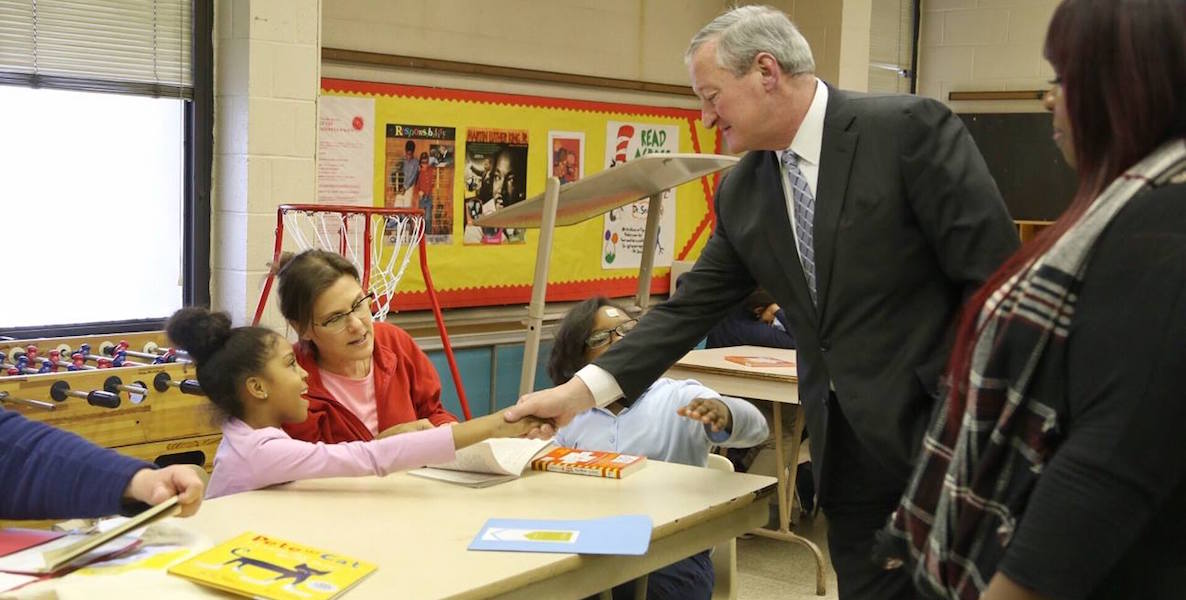

On a Saturday afternoon, Vietlead's youth apprentices and support staff meet to strategize their campaign for healthy schools and community control of land. Photo by Katherine Rapin