Name a major American city, and I’ll tell you about a sports stadium controversy. In Philadelphia, the 76ers are trying to build a stadium downtown, but facing intense local opposition over traffic and the potential for heightened gentrification. In Washington, D.C., the Washington Capitals and Washington Wizards wanted to build a new stadium in Alexandria, VA, but the deal got nixed from the state budget. You may have heard how Travis Kelce and Patrick Mahomes urged the public to vote in favor of a tax to build a new downtown stadium in Kansas City, only to be denied in an April primary vote.

After decades of building stadiums with the support of public subsidies, is the tide finally turning against this trend?

It may be that citizens, and local and state governments are getting smarter about the shady math equating stadiums with economic development.

The Brookings Institution has long questioned the evidence that stadiums are smart economic development, going back to the 1990s when Andrew Zimbalist published a book on the subject, Sports, Jobs and Taxes: The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Stadiums. Sports stadiums have a pathetically short lifespan — many last only 30 years before they are seen as too outdated. So it’s no surprise we’re in the second cycle of stadium deals 30 years after the rush to build stadiums in downtowns in the 90s.

This time around people are much more wary that these stadium deals pay off. Recently on LinkedIn, Alan Berube, Interim Vice President and Director of Brookings Metro succinctly explained why stadiums in general (and the Alexandria stadium in particular) are not the economic drivers they seem to be:

Yet, for cities that aren’t generating tons of money through other forms of economic development, stadiums are especially enticing. And so many cities are trying to have their cake and eat it too: they’re trying to convert the “aggregate output” into “high-road” industry by combining stadiums with other kinds of economic activity, namely housing and mixed-use commercial retail.

For example, in Philadelphia, while there’s great opposition to the downtown 76ers stadium, an alternate stadium development plan in South Philadelphia aims to augment the stadium with a hotel, concert venue and retail district, and then later to convert a sea of parking lots nearby into more than 2,000 units of housing. By contrast, this $2.5 billion plan has been roundly applauded.

This kind of “stadium neighborhood” approach is a step above the drive-in-and-out for a game kind of economic development. It’s been put to use in Los Angeles at the SoFi Stadium district, which includes 1.5 million square feet of retail, restaurants, and 2,500 units of housing, and The Hub on the Causeway, a development that combines office, residential, and retail adjacent to the TD Garden in Boston.

But I bet stadium neighborhoods will soon also seem passé. These stadium neighborhoods aren’t really producing the kind of amenities that residents need — they’re just diluting the impact of an entertainment zone with urban density, hoping people won’t notice the stadium, the tourists, the sports bars if they’re masked by luxury condos and restaurants.

There are some interesting examples of how a third wave of stadium projects are moving beyond these old iterations of stadium development.

Citizens, and local and state governments are getting smarter about the shady math equating stadiums with economic development.

My favorite example of what a better stadium neighborhood could look like is Willetts Point in Queens, New York. The project will transform 23 acres of public, formerly contaminated land into 2,500 units of affordable housing, a new public school, and 40,000 square feet of public open space — in addition to New York’s first soccer-specific stadium. Because the land was owned by the City, the NY Economic Development Corporation was able to broker a better deal for the City, resulting in some desperately needed assets. There’s a difference between the usual stadium district and the affordable housing and public schools found here.

But a stadium that is essentially open only to ticket holders is also problematic. In Boston, a not uncontroversial renovation of a dilapidated stadium will provide playing fields for Boston Public Schools, while also enabling Boston Unity, a National Women’s Soccer League team, to use the stadium. Aside from university graduations, I can think of few times when our major stadiums are open to the public, so this is an improvement. Why shouldn’t our stadiums have more access to the public, especially if these stadiums rely on public subsidies, infrastructure, zoning variances or other public goods?

Meanwhile, in Paris, the soccer Paris FC is experimenting with kid-friendly game times and free tickets. These interventions have not only boosted attendance, but could build a culture of recreation.

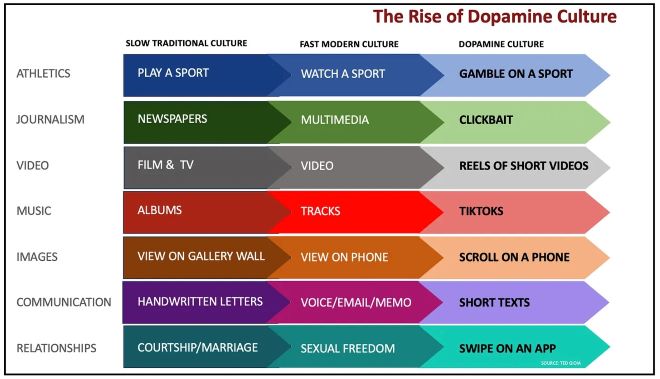

This distinction between a culture of recreation and entertainment is increasingly important as our society contemplates how to fight dopamine culture. A viral chart by Ted Gioia about the rise of dopamine culture shows how we have moved from having people play a sport, to watching a sport, to gambling on a sport.

There’s been a ton of discussion recently about the problems with young people and social media, but very little discussion about how cities should respond. A clear answer is to think about engaging young people in more physical activity, making it near impossible to be using screens at the same time, elevating the positive social aspects of playing games, and boosting endorphins from physical activity. The lack of leadership on this issue makes it clear that we need cities to assign physical activity to someone.

Currently we don’t really have a bridge between our obsession with sports teams (and their stadiums) and the culture of recreation. Cities have long combined parks and recreation, because recreation often relies on public space. But while park design has seen great innovation and evolution in recent decades, many cities’ approaches to recreation feels dated and dull. Look at Little Island or The High Line in New York, and you can’t help but feel that these public spaces have advanced beyond the concept of 20th century public space. But where can you find a truly 21st century approach to public recreation programs in cities?

We may need a “Sports Mayor”

Cities have created Chief Sustainability Officers, Chief Resilience Officers, and Nighttime Mayors as cross-sector leaders who coordinate around their specific focus area. A “Sports Mayor” (better title, TBD) would advocate for ways of increasing physical activity throughout our cities and better connecting our stadiums to a real civic purpose in our cities. A strategic plan for recreation and physical activity might help us to look beyond rec centers as the sites of physical activity in our cities. It might also help us to quantify the sincere lack of space we provide for recreation, and the economic, social and even environmental opportunity cost to cities by not fulfilling that need.

I find the debate over what to do with pickleball as a particularly illuminating example of how we just don’t know what to do about public sports programs. Interest in pickleball has surged, and there’s not enough sanctioned space for picklers to play. As a result, players have popped up their own nets on public spaces — but even that move has been turned into a misdemeanor in some testy communities. Why aren’t we doing everything we can to enable people to play and to reap all the physical, mental and social benefits of sports?

A Sports Mayor would not only find places to play, but advocate for other ways to enhance physical activity, such as school streets and bike share, as well as mobility and access for seniors and those with disabilities.

What might be the economic impact of heightening physical activity and sports across a city? As opposed to parks and public spaces that people won’t pay for, residents will pay for using sports facilities, making these opportunities more financially sustainable. A physically active population reduces the public cost of health care, and rec center coaches are also probably a lot cheaper than public school counselors to deal with depressed teens. We’d need some real economic analysis here, but my guess is that it would cost a lot less than a stadium and have a greater civic impact, if not an economic one.

Diana Lind is a writer and urban policy specialist. This article was also published as part of her Substack newsletter, The New Urban Order. Sign up for the newsletter here.

![]() MORE ON THE POTENTIAL SIXERS STADIUM

MORE ON THE POTENTIAL SIXERS STADIUM

Comcast Spectacor’s Phase 1 plan will span Lots G and H of the complex and will include upgrades to Xfinity Live!, a 5,000+ seat concert venue, a hotel, new retail and restaurants and an outdoor plaza. Photo courtesy of Comcast Spectacor.