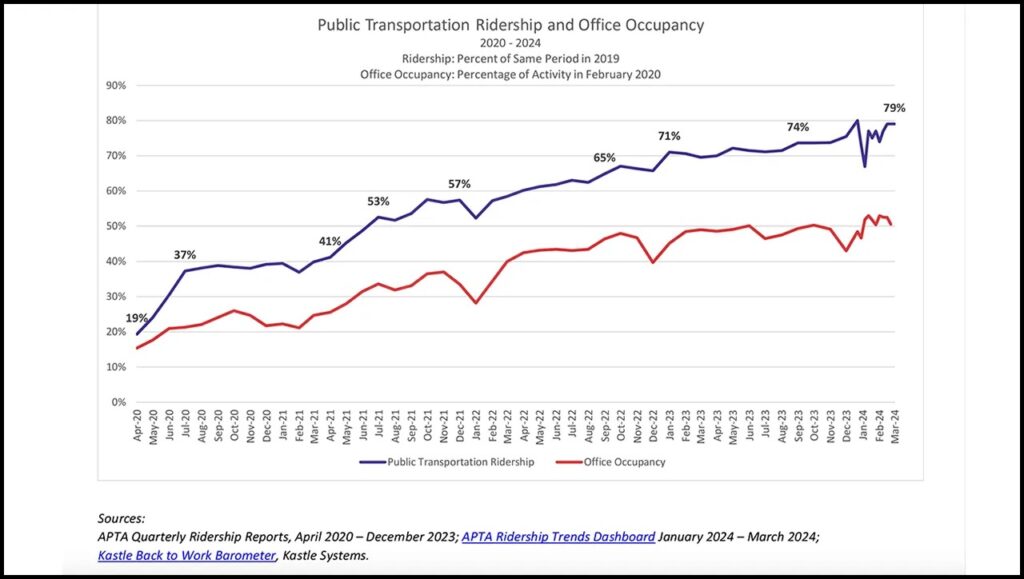

American public transit ridership is still broadly down 21 percent since March 2020, averaging between modes like buses (down just 19 percent) and commuter rail (down 35 percent). Transit’s recovery lag is largely seen as a function of remote work, with many reports showing office occupancy and ridership rates in lockstep.

Things get more interesting when you see these rates diverge, showing just how many transit trips might have nothing to do with work. For example, Philadelphia’s Center City District estimated office occupancy at 57 percent last summer, which would put it above average office occupancy. Yet SEPTA, our regional transit provider, which had its second-highest recovery rates in March 2024, has seen its subways reach only 56 percent of pre-pandemic levels, regional rail at 66 percent, and buses at 72 percent. Why does Philly have above-average office occupancy but below-average post-pandemic transit ridership? (There’s a whole other column in that answer.)

What about cities with low office occupancy and high transit ridership? These cities point to the future of transit, suggesting that the way forward for post-pandemic cities is to look beyond the commuter or provide different kinds of transit that better compete with driving or rideshare. Seattle, for example, has one of the lowest office occupancy rates, and yet its Sound Transit light rail has rebounded to pre-pandemic levels.

Indeed, as the Brookings Institution has noted, commuting only makes up a small share of travel overall:

The vast majority of travel in the U.S. is not related to getting to or from work. The 2017 NHTS found that only 23 percent of trips were commutes. Yet before the pandemic, the highest-ridership American transit systems received a disproportionate share of their ridership from commutes.

Alissa Walker wrote in New York magazine that transit agencies have had to think beyond rush hour:

The new normal for big-city transit agencies is the off-peak rider. The pandemic subway is a different system than what cities have known in the past. The same numbers of people aren’t flooding into central business districts every weekday, but ridership for many agencies has surged on afternoons and weekends.

Cities that are figuring out how to leverage transit for non-commuting purposes are winning. One of those cities is London, where despite having a remote work rate that rivals American cities like San Francisco (where weekday ridership on BART is just 40 percent of pre-pandemic levels still!), London ridership rates exceed pre-pandemic levels on the Tube on weekends.

How London does it

London has seen an acceleration of remote work just like many American cities — it has office occupancy rates that seem quite low (just 35 percent?) and fully remote work from home rates that seem quite high (almost 20 percent) when compared with the U.S.

But unlike many American cities, London has really focused on transit to spark its post-pandemic recovery. London is lucky first of all to have a smart, forward-thinking mayor, but to also have a mayor who is in control of his city’s transit agency. (Does any American city have this advantage? I can’t think of one.)

Transportation is seen by many as Mayor Sadiq Khan’s legacy.

-

- He oversaw the introduction and expansion of the Ultra-Low Emission Zone, which requires drivers of older, more polluting cars to pay a fee to drive in London.

- Kahn has also boosted funding to Transport for London when it was losing passengers during the pandemic.

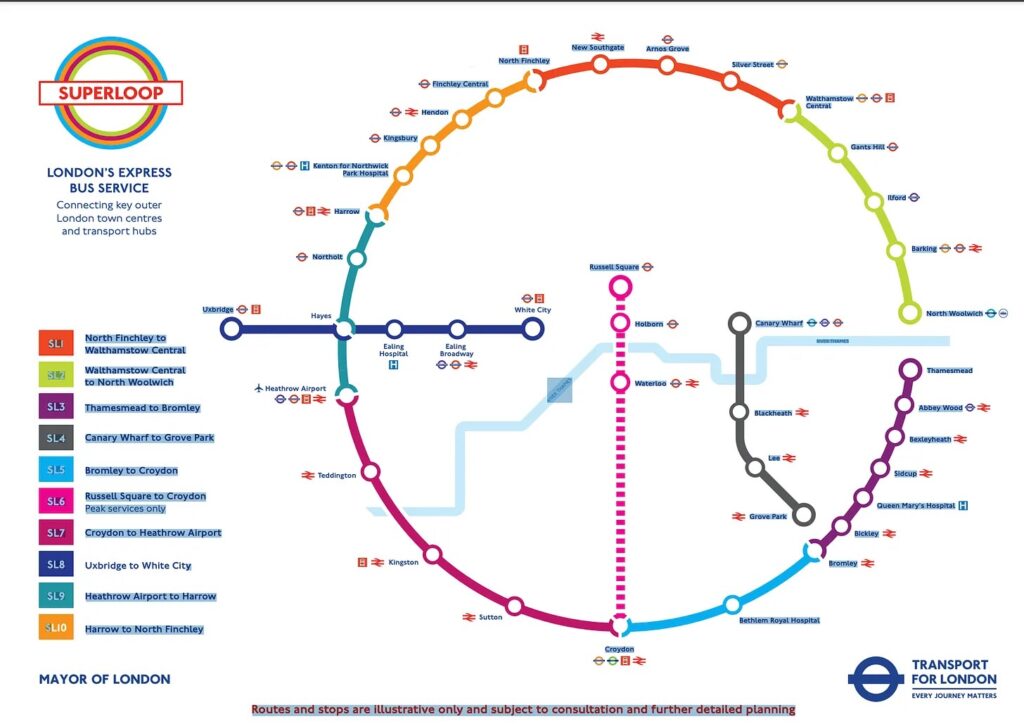

- London hasn’t focused its transit recovery strategy only on going people downtown. It has focused on getting Londoners to other locations. The greatest evidence of this strategy has been the launch of the Superloop last summer. The Superloop is a network of 10 express bus routes in outer London that circle the entire capital. Instead of connecting people to central London, it connects people to commercial centers, hospitals, schools and transportation hubs.

Early ridership data shows the successes of the network — with demand growth in the initial routes 15 percent higher than the network average. In total, the new Superloop services have added more than 6 million bus kilometers (3.8 million miles) to the capital’s network. Additionally, more than 95 percent of Londoners now live within about 1,300 feet of a bus stop.

In addition to the Superloop, nearly a decade ago Khan instituted something called the Mayor’s Hopper Fare, which is essentially a free transfer within one hour. In other words, he’s made a long term commitment to making buses less expensive and making them conducive to quick transfers that get people where they need to go.

Now Mayor Khan is staking his third term on the idea that people want a next level of Superloop.

All of this work points to the importance of investing in transit that isn’t solely about getting commuters back to the office. The Superloop doesn’t focus on getting people into London, it’s about connecting people to other parts of the city. If 75 percent of all travel isn’t a commute, how can transit agencies get people to choose transit for all those trips?

Cities like Charlotte, NC are still considering investing in commuter rail. The infrastructure is sexy, but perhaps London shows that there are other steps cities could take to increase transit usage. Make it harder to drive into the city while making it easier and cheaper to use buses. Connect people to the places they want to go, not where the business community or the government thinks they should go.

Maybe it’s time to really think outside the box — and perhaps into a circle, like London.

Diana Lind is a writer and urban policy specialist. This article was also published as part of her Substack newsletter, The New Urban Order. Sign up for the newsletter here.

![]() MORE ON PUBLIC TRANSIT

MORE ON PUBLIC TRANSIT