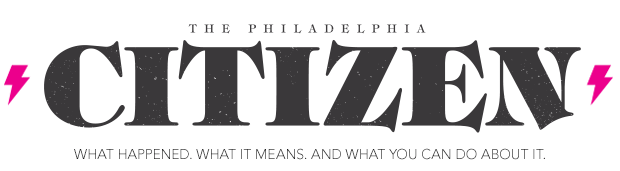

If you do nothing else today, tune in to WURD radio, 96.1 FM. To commemorate the 34th anniversary of the MOVE bombing, the station will be preempting its regular programming between 2 and 5:30 pm for a special show co-hosted by Dr. Aaron Smith and Eric Grimes that will break some long-overdue new ground. It will feature former Mayor Wilson Goode, MOVE Commission member Graham McDonald, journalist and historian Linn Washington; Mike and Debbie Africa were also invited. Here’s hoping that today’s show could be the first step, 34 years too late, at reconciliation.

“There’s a lot of unresolved pain and suffering from this time and we hope through a series of honest conversations, the healing process can continue,” says WURD President and CEO Sara Lomax-Reese.

![]() If you aren’t well-versed on MOVE, it could be argued that it’s our city’s perpetual albatross, a tragedy of leadership and moral failing that haunts our story and our collective attitude to this very day. MOVE was a self-professed radical group; not only were nine members convicted of killing a police officer in 1978, they terrorized a predominantly black working class neighborhood for years, stockpiling weapons, flaunting basic hygiene, and blaring obscene political messages through a bullhorn at all hours. When city officials, unable or unwilling to deescalate the standoff, decided to drop a bomb on its own citizens, killing women and children and decimating a middle-class black neighborhood, it colored everything after. Ever since, we’ve been suffering from post-traumatic stress.

If you aren’t well-versed on MOVE, it could be argued that it’s our city’s perpetual albatross, a tragedy of leadership and moral failing that haunts our story and our collective attitude to this very day. MOVE was a self-professed radical group; not only were nine members convicted of killing a police officer in 1978, they terrorized a predominantly black working class neighborhood for years, stockpiling weapons, flaunting basic hygiene, and blaring obscene political messages through a bullhorn at all hours. When city officials, unable or unwilling to deescalate the standoff, decided to drop a bomb on its own citizens, killing women and children and decimating a middle-class black neighborhood, it colored everything after. Ever since, we’ve been suffering from post-traumatic stress.

Think I’m being overly dramatic? Well, then, you haven’t studied Buffalo Creek, West Virginia.

Early in the morning on Saturday, February 26, 1972, residents of Buffalo Creek heard a loud roar. Moments later, the tiny hamlet was ensconced in a flood of biblical proportions, 30-foot waves crashing down on the valley, sweeping up and wiping away everything in its path. Turns out, a sloppily-constructed, man-made dam at the top of the hollow, owned by the Pittston Coal Company, had burst.

When our city decided to drop a bomb on its own citizens, killing women and children and decimating a middle-class black neighborhood, it colored everything after.

And so, literally within minutes, on a sleepy Saturday morning, 126 people were killed and no less than 4,000 were left homeless.

In the decades since, the Buffalo Creek flood has been one of the most examined cases in the psychiatric field of trauma study. Teams of clinicians and researchers have monitored the town—or what’s left of it—and the survivors ever since, in an effort to understand the longstanding effects such a tragedy can have on a community.

It should come as no surprise that Buffalo Creek remains a hotbed, even today, of post-traumatic stress disorder. A study by the American Journal of Psychiatry found that the PSTD “cluster” of Buffalo Creek featured widespread symptoms of “avoidance” and “numbing.” It was as if the waters had washed away the very notion of progress. Even long after the tragedy, it was as if time itself had stopped.

“The only thing I like today about Buffalo Creek is the new road,” Rev. Robert Peters, whose parents were killed in the flood, told the Logan Banner a decade ago. “We used to have sidewalks, and you could buy anything at the Lorado Company Store. Furniture, dry goods, hardware, even a tailor-made suit. We had a movie theater, barber shop and a beer garden.”

That so little has been rebuilt in the ensuing years, that so little progress has been made, can no doubt be attributable to a confluence of factors. But chief among them, no doubt: Avoidance and numbing.

Avoidance and numbing. Sound familiar, Philadelphia?

Today, our own version of Buffalo Creek rarely gets talked about, but that doesn’t mean it’s not omnipresent. The city’s 1985 bombing of the West Philly headquarters of MOVE, oft-described as a radical, back-to-nature group, resulted in a blaze city officials allowed to burn until 11 people, including five children, were dead, 61 homes were destroyed and 250 people were left homeless. Philadelphia found itself making a type of national news it hadn’t sought, as when, in his opening monologue the next night, David Letterman said, “I just want to know one thing. Does this mean MOVE won’t get its security deposit back?” Or when USA Today ran a cartoon of Mayor Wilson Goode as fighter pilot, wearing a Snoopy-like leather helmet in a plane’s cockpit.

At the time, local outrage was palpable. The mayor appointed a commission whose findings called the bombing “unconscionable,” suggested that the 11 deaths might be “unjustified homicides,” (a grand jury later disagreed), and concluded that Goode had “abdicated his responsibilities as a leader.”

The only way to move past avoidance and numbing is to deal with your pain. When Goode sits down with members of the Africa family whose lives were ripped apart by his decision-making, a whole city will be there with them, reconciling ourselves with our past.

Today, though, a curious thing has happened. MOVE seldom is part of our civic conversation; when it does make an appearance, it’s usually in a political context, as when during this mayor’s race a pundit, arguing for the inevitability of Mayor Kenney’s reelection, will observe that we once had a mayor who dropped a bomb on a city block…and even he was reelected.

In many ways, one might think Philadelphia has moved past the tragedy of MOVE. Center City is booming, population is on the upswing, and our sports teams are winning. But remember the lesson of Buffalo Creek, and the lingering effects of trauma.

“I think the MOVE bombing is right up there with the collapse of the ’64 Phils in terms of being a scar on the city’s psyche,” Zack Stalberg told me years ago, when I first started seeing in Buffalo Creek parts of our own story. Stalberg, the former Committee of 70 CEO and onetime editor of The Daily News, was a newspaper reporter at the scene on the day of the bombing. “It said to us, this is a place in which authorities could and would wipe out an entire city block because they weren’t smart or patient enough to resolve the problem peacefully. And it said to us, this is a place where a mayor can get reelected after bombing his own city and killing several of its citizens.”

Refusing to come to grips with hard truths like those about who we are, and who we want to be? That can result in some serious avoidance and numbing.

On the morning of May 13, 1985, the future of Philadelphia could have gone a ![]() very different way. At lunchtime that day, the day of the bombing, the city’s business leaders were gathering at 17th and Market to break ground on a bold new venture, something that announced the city’s renunciation of its parochial and Quaker past. On that day, ground would be broken for the building of Liberty Place, the first skyscraper in our skyline-deprived metropolis to violate the longstanding gentlemen’s agreement to not exceed the height of William Penn’s statue atop City Hall.

very different way. At lunchtime that day, the day of the bombing, the city’s business leaders were gathering at 17th and Market to break ground on a bold new venture, something that announced the city’s renunciation of its parochial and Quaker past. On that day, ground would be broken for the building of Liberty Place, the first skyscraper in our skyline-deprived metropolis to violate the longstanding gentlemen’s agreement to not exceed the height of William Penn’s statue atop City Hall.

Change was in the air. Like the rest of the country, Philadelphia had gone through some dark times in the ‘70s. There was the racial divisiveness of the Rizzo years, there were televised fistfights on the floor of City Council, (starring, in this corner, future mayor John Street), and there was rampant crime and dirty, abandoned streets.

Yet, Wilson Goode was riding high, and Philadelphia was feeling pretty good about itself—at least as good as Philadelphia can. As the city’s first black mayor, Goode was seen as a symbol of racial reconciliation and, as the city’s previous managing director, he was heralded for his technocratic competence. In Goode’s first year, he received national praise for bringing into City Hall all the wild youths who were defacing public property with graffiti and enlisting them on a crusade to beautify the city by making public art. (His Anti-Graffiti Network would eventually morph into the renowned Mural Arts Program). In early 1984, there were even reports that Goode was being considered for the vice-presidential slot.

What followed MOVE was decades of avoidance and numbing. We’ve gotten more public official perp walks and shrugs from a shell-shocked electorate. When, after all, was the city’s last bold, creative idea?

All those good vibes changed a few hours after the first shovel was plunged into the earth on the Liberty Place site. Over the next weeks, Goode’s image, like his city’s, was in shambles. On the day of the bombing, he watched the horror from his office, on a grainy black and white TV, not in constant contact with his lieutenants and never coming to ground zero, because, he later wrote, he’d been told that “unknown members of my own police force had targeted me for death.” Days after the bombing, he said he didn’t consider the explosive device a bomb or know anything about any helicopter.

The bombing eroded any faith Philadelphians had in government, and ushered in an era of widespread governmental incompetence; the city couldn’t even rebuild the homes it had destroyed. The developer of the new Osage Avenue homes was jailed for stealing money from the project. Once built, the plumbing, roofing and insulation were all faulty. Fifteen years after the bombing, when the homes had still not been properly repaired, then-Mayor Rendell told Osage residents that he was committed to getting it right. His successor, however, decided to demolish the homes, offering each homeowner $151,000. Twenty four homeowners rejected the offer and sued Mayor John Street for breach of contract, winning a $13 million federal jury verdict.

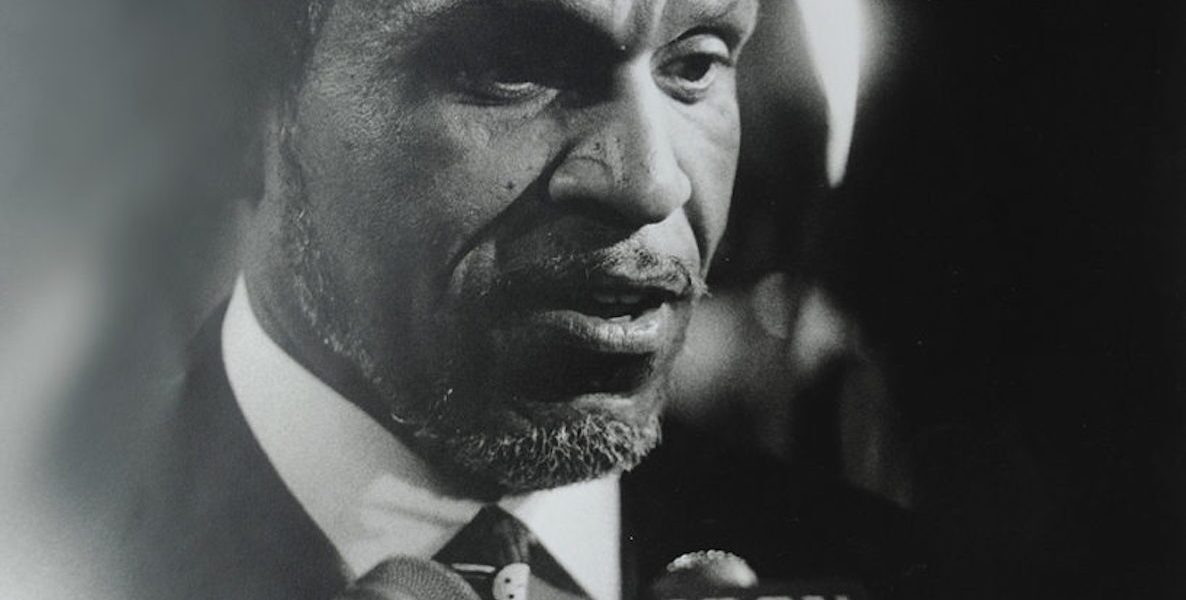

![]() What followed MOVE was decades of avoidance and numbing. Oh, sure, Rendell took on the unions in his first term and had a winning personality, but, by and large, the city’s political leadership has played small ball ever since. Poverty? Education? A Marshall Plan for hollowed-out neighborhoods? Puh-leeze. Instead, we’ve gotten more public official perp walks and shrugs from a shell-shocked electorate. When, after all, was the city’s last bold, creative idea?

What followed MOVE was decades of avoidance and numbing. Oh, sure, Rendell took on the unions in his first term and had a winning personality, but, by and large, the city’s political leadership has played small ball ever since. Poverty? Education? A Marshall Plan for hollowed-out neighborhoods? Puh-leeze. Instead, we’ve gotten more public official perp walks and shrugs from a shell-shocked electorate. When, after all, was the city’s last bold, creative idea?

Like Buffalo Creek, it could be argued that, when it comes to the big stuff, time seems to have stopped after MOVE. It’s like we’re a city of Marty McFly’s, all stuck in 1985: there’s our antiquated glass ceiling, our atavistic racial discourse, our failure to do what peer cities like Pittsburgh have done and reinvent ourselves from an industrial era wasteland into a vibrant, entrepreneurial economy.

It’s as if the collective scar Stalberg referred to—MOVE and the ’64 Phils collapse, the worst in history, up 6 and one-half games with 12 to go, only to blow it—it’s like those blows rendered us paralyzed, afraid to move forward. What we’ve gotten, instead, from our leaders, is timid incrementalism. (Soda tax, anyone?)

That’s why WURD’s programming today is so important. The only way to move past avoidance and numbing is to deal with your pain. If Goode—a man of God, now—ever gets the chance to sit down with members of the Africa family whose lives were ripped apart by his decision-making, a whole city will be there with them, reconciling ourselves with our past. Maybe rather than burying our history, we should take a page from South Africa under Nelson Mandela and have our own Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a public tribunal dedicated to restorative justice after the horrors of apartheid, in which both victims and perpetrators of violence told their stories and either forgave or asked for forgiveness.

Maybe that’s the only way to get past our shit and ultimately get to problem-solving. Maybe that’s how we get past the scar of MOVE.

The best advice I’ve ever heard about how to think about the tragedy that is MOVE came from none other than the most unlikely philosopher prince, the former heavyweight fighter and movie actor Randall “Tex” Cobb, who for many years lived near the site of the bombing. “You had a bunch of assholes who didn’t bathe and called that politics,” Cobb said. “And then the city reacted like a freakin’ redneck. Okay. Score tied on the stupid meter. Don’t you think it’s time to get your Mojo back?”

Tune in to WURD today. And then let’s get our Mojo back.

Monday, May 13, 2 pm-5:30 pm, on WURD radio, 96.1 FM/900 AM or stream it live here.

Header: Temple University Archives