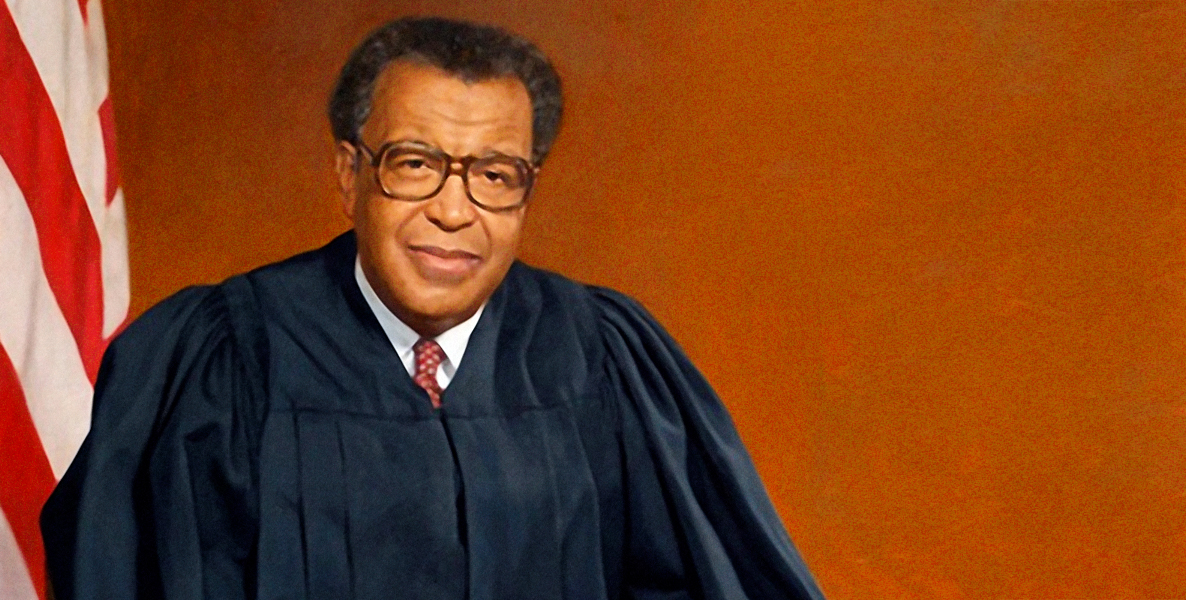

In 2006, long before Andrea Constand and other women would publicly come forward to accuse Bill Cosby of drugging and sexually assaulting them, Michael Eric Dyson wrote a book entitled Is Bill Cosby Right? (Or Has The Black Middle Class Lost Its Mind). In it, the best-selling author and then-Penn professor, who now teaches at Georgetown University, proclaimed the legendary comedian as “lacking in moral authority.”

The evidence, Dyson posited, was in the way Cosby bullied and derided young, poor African-Americans: “Everybody knows it’s important to speak English except these knuckleheads. You can’t land a plane with ‘why you ain’t…’ You can’t be a doctor with that kind of crap coming out of your mouth,” Cosby said in a 2004 NAACP speech.

“I took a lot of crap for that,” Dyson told me when I texted him yesterday. And he took it, especially, from the black community; many accused the iconoclastic author of seeking to take down an African-American icon.

I’d been thinking of Dyson a lot lately, especially after our Starbucks imbroglio here in Philly. Dyson and I became friendly when he was at Penn; we bonded over a bad 76ers team and the writings of James Baldwin. What intrigued me about him then remains so today: He’s willing to take on sacred cows and he’s willing to challenge orthodoxy…even his own.

Take his most recent book, Tears We Cannot Stop: A Sermon To White America. It’s an important contribution because, in it, Dyson makes a concerted effort to move beyond the usual fault lines of what passes for racial discussion in America: grievance from one side, defensiveness from the other. Instead, he offers solutions, and a road map for white allies interested in the cause of racial justice.

It’s fitting, then, that we spoke for an hour yesterday, just after Cosby’s conviction. What follows is an edited and condensed version of our conversation.

LP: It must be interesting, sitting there and watching Bill Cosby found guilty. In a way, you were his first accuser.

MED: It’s funny, on CNN they just called him a “public moralist.” That’s the phrase I used in my book. He was going around the country condescendingly giving nasty and vicious moral lessons to young African American people, and all the while he was hiding this fact about drugging and abusing women.

White brothers and sisters have taken my suggestions to make reparation at the local or individual level: You can hire black folk at your office and pay them just a little bit more than you would normally. Or you can pay the black kid who cuts your grass double what you might ordinarily pay. Think of it as a secular tithe.

Growing up, Bill Cosby meant a lot to me, even before “I Spy” and “The Cosby Show.” In 1968, Andy Rooney wrote and Cosby narrated the TV special “Black History: Lost, Stolen or Strayed.” I remember watching it as a kid and learning how 500 years of African-American history had been wiped away. When I criticized his NAACP speech, he called me and told me The New York Times misquoted it. I was, like, “Uh-oh. I screwed up.”

Then he sent me the speech and I saw he did say all these angry, problematic Read Tears We Cannot Stop Do Something

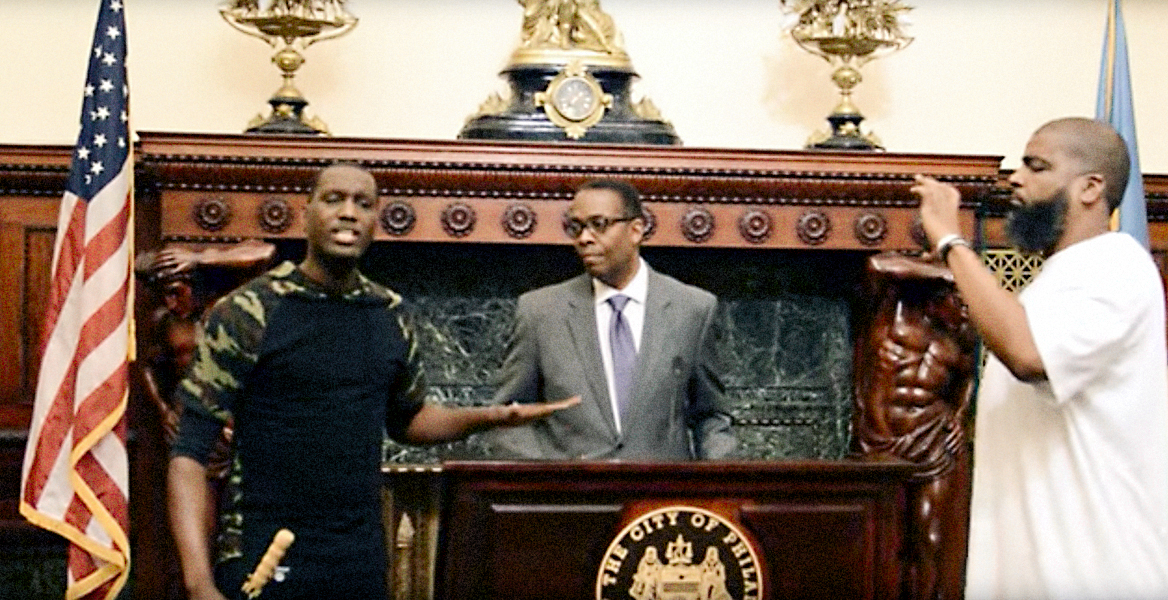

It is interesting how times change. Now, Meek Mill is out of jail and heralded as a hero and here’s Cosby, who spent all that political capital castigating young men like Meek Mill, and now he’s shunned.

LP: That’s a good point, but with all the hoopla this week surrounding Meek Mill’s release, I’d just caution that he’s no Nelson Mandela.

MED: [Laughter] I hear that, I hear that. Yet whatever flaws he possesses, he’s become a symbol of all that’s wrong and deeply tragic with our criminal justice system. The real significance of Meek Mill is to get us to focus on the so many millions more who don’t have a name and who don’t have sports team owners coming to their defense, who are trapped in a horrible system.

LP: Living through the Starbucks drama here, it felt to me like too familiar a narrative: The calls for the firing of the manager, the protests. And then we’ll move on to the next race issue du jour.

MED: As corporations go, Starbucks has tried to demonstrate some sustained vigilance around race. Some thought it was goofy, but remember a couple of years ago? They were writing race messages on cups and having in-store discussions. So, all corporations ain’t the same. And I think this was bigger than Starbucks. Calling the cops in the first place was ridiculous, let’s be real. That’s about implicit bias. Starbucks is an easy target for the release of our racial anger, but the anger comes from the sense of all we can’t do without the fear of getting shot or hassled by the police.

It is interesting how times change. Now, Meek Mill is out of jail and heralded as a hero and here’s Cosby, who spent all that political capital castigating young men like Meek Mill, and now he’s shunned.

Did you see that the cops were called because some ladies were golfing too slow? What the fuck? We can’t golf, can’t drink coffee, can’t sell loosies, can’t drive too fast or too slow. It’s easy to protest Starbucks. The difficult thing is to figure out what this fear of Black people is all about.

LP: That said, Tears We Cannot Stop is all about asking well-intentioned whites to be part of the solution. During the Starbucks story, I thought of this passage: “When a black or brown youth is railroaded in a court system for possessing a negligible amount of marijuana, it makes a difference if a sea of white witnesses floods the airways, or cyberspace, or community halls, or prosecutors’ offices…with emails, letters, speeches and commentary about the injustice of such acts. If white folk take to social media and testify to how they got away with the very minor offenses that cause black and brown folk trouble…it might move the needle of awareness and set change in motion.”

MED: Yeah, bless the heart of that young white woman who posted that video from inside the coffee shop that day. In the age of Trump and all its insidious bigotry, the reappearance of the white liberal is to be greatly celebrated. Like my man who showed up that day, who was meeting those two brothers, and he said, “What’d they do? They didn’t do anything.” He was using his white privilege to say something that advances justice.

LP: I worry that that phrase—“white privilege”—is strategically counterproductive. Think of the sizable number of white, working class voters, particularly in Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin, who voted twice for Obama and then for Trump. They certainly don’t feel privileged.

MED: Yeah, yeah. The fact is, those in the white working class have more in common with black folk than with the white overlords, and we need a way to re-describe all that. Remember when Martin Luther King Jr.’s white jailers came to him in that Birmingham jail and said, ‘Segregation is right.’ He asked what their salary was and, when they told him, he said, ‘You should be marching with us.’ A whole lot of white people feel they’re the victims of racism, and that’s a function of scapegoating. So many whites have been scared into thinking blacks are taking over by politicians looking to exploit them. Race is a proxy for class.

But let’s be real. If you can talk to a cop without the fear that you might get shot, you got some kind of privilege. You also have the privilege of association. People hire who they know and are comfortable with, and to be on the receiving end of that is a type of privilege, too. The hardest part about privilege is knowing you have it. I mean, I got a helluva lot of male privilege. And there have been times when I haven’t been aware of that.

We can’t lose sight of each other’s humanity. That’s why, when Brother Bill Maher made a mistake and used the “N” word, I wasn’t going to throw a white ally away. I went on his show and took a lot of shit about it from the black community. But the goal is justice, not vengeance.

LP: Yet, I want to be clear here. Tears We Cannot Stop isn’t a compendium of grievance, racial or otherwise. It’s actually a sermon to white America and an invitation for the well-intentioned in all races to work together.

MED: I still get letters to this day from white brothers and sisters telling me how moved they were by the book. They’ve taken my suggestions to make reparation at the local or individual level: You can hire black folk at your office and pay them just a little bit more than you would normally. Or you can pay the black kid who cuts your grass double what you might ordinarily pay. Think of it as a secular tithe. You can set up an I.R.A.: an Individual Reparations Account. There are thousands of black kids whose parents can’t afford the cost of tutors or to send them to summer camp.

See Dyson talk Cosby with Bill MaherVideo

LP: Well, and intent matters, right? He didn’t intend to use the word to wound. There was no hate behind the word, right?

MED: Right! He called himself a “House Nigga.” He wasn’t saying Michelle Obama was ape-like. We’ve gotta be smart about what gets the death penalty. We can’t throw white allies away.

LP: You’ve touched on Cosby, defending Maher. You’ve taken on a lot of sacred cows, including defending homosexuality in the black community.

MED: Man, what Kanye thinks he’s doing now, I been doing for years. [Laughs]

LP: How does that differ from what Cosby was doing back in the day? Wasn’t he, like you, offering up some tough love?

MED: You gotta have the love before you get tough. I remember preaching in a Church and this black woman comes up to me and says, “You know you’re going to Hell because you say that God created gay people!” I said, “Are you telling me there’s another God?” I said, “Sorry, but you’re using God to co-sign your bigotry.”

Black America doesn’t want to tell the truth about black ministers in pulpits who are saying gay people are going to Hell, but who are themselves closeted. Corporal punishment? We claim we love our children, but many in our community beat them to within an inch of their lives. We’ve got to be lovingly self-critical and lovingly honest about our issues, and challenge ourselves to do better.

LP: What’s next for Michael Eric Dyson?

MED: My book What Truth Sounds Like: Robert F. Kennedy, James Baldwin, and Our Unfinished Conversation About Race comes out on June 5.

LP: Oh, man. Two heroes of mine. Let’s bring you to Philly to discuss and sell some books?

MED: Deal.

Header: Matt Slocum via Shutterstock