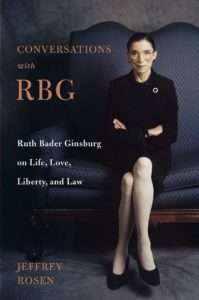

[Editor’s note: This story originally ran last November, shortly before National Constitution Center CEO Jeffrey Rosen debuted his book, Conversations with RBG: Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Life, Love, Liberty and Law, in a conversation with veteran Supreme Court reporter Dahlia Lithwick. On Thursday, the Constitution Center awarded Ginsburg its Liberty Medal. On Friday, the Justice died.]

National Constitution Center president and CEO Jeffrey Rosen’s new book, Conversations with RBG: Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Life, Love, Liberty and Law, is a compendium of conversations he’s held with Ginsburg over the last 25 years. If, in these fractured, uncivil times, you’re looking for a voice that reminds us of our shared value of reason and civility, Rosen is your man; he’s a true believer in the transformative power that all his beloved Founders stood for in their striving for a more perfect union: Respectful debate, civility, citizenship.

With his latest, Rosen gives us Ginsburg; whether you agree with her judicial rulings or not, you can’t argue with the strength of her intellect or the breadth of her influence. We began there, on the curious emergence of the Notorious RBG pop-culture brand. What follows is a condensed and edited version of our conversation:

With his latest, Rosen gives us Ginsburg; whether you agree with her judicial rulings or not, you can’t argue with the strength of her intellect or the breadth of her influence. We began there, on the curious emergence of the Notorious RBG pop-culture brand. What follows is a condensed and edited version of our conversation:

Larry Platt: You’ve spent all this time with Justice Ginsburg. She’s become a cultural touchstone—movies are made about her, and SNL regularly parodies her. Can you explain the RBG pop culture phenomenon?

Jeffrey Rosen: It has surprised Justice Ginsburg as much as anyone. At one point, her law clerks had to explain to her who Notorious BIG was. It’s astounding to have seen her celebrity grow, encompassing those two movies, not to mention all the merchandising. A generation of young women and men have been inspired by this vision of a strong older woman, someone who bucked stereotypes, who was never meek, and who today is one of the most significant liberal constitutional voices in American history.

Watch the National Constitution Center's tribute to RBGDo Something

LP: Why do you think her example has resonated so much, particularly for young women?

JR: Because she’s just such a boss. [Laughs] She is superhuman in self-discipline, in productivity, in her dedication to the job. At an age when most people are retired, she’s at the height of her powers.

This is what Madison and the Founders meant by the “pursuit of happiness”—they weren’t referring to the act of purchasing the latest iPhone or hitting the “Like” button. They were talking about reading deeply in order to cultivate the foundation of reason in order to serve a public good.

I am extra lucky that, for the past 25 years, I’ve spent so much time in her presence, and it’s like being in the presence of one of the Founders.

LP: She speaks in the book of the power in listening. That skill would seem to be in short supply these days. Is there something in her example that points the way toward greater civility and citizenship?

JR: Interviewing Justice Ginsburg is a unique experience. All of her colleagues and friends know to wait during these long pauses between your question and her answer. During those pauses, she’s thinking carefully, as she’s about to say something important. And she’ll say it in complete sentences and full paragraphs. She listens and responds carefully and thoughtfully, and isn’t that we need more of?

You know, Justice Ginsburg and Justice Scalia were close friends, and she talks movingly of her friendship with him. But at the same time, she’s critical of some of the harshness of his rhetoric, like when he said that Justice O’Connor’s opinion couldn’t be taken seriously. For Justice Ginsburg, it’s important for a judge to model civility. She could use vivid metaphors in her opinions, but she would never be disrespectful.

LP: You’ve walked the talk at the Constitution Center, modeling civility and nonpartisanship, even in your choice of the last two chairmen: Joe Biden and, now, Justice Neil Gorsuch. I wonder, though, if that can feel limiting when the Constitution feels under assault. Yours is a voice that could credibly cry foul when someone—anyone—violates constitutional norms. At times like these, does remaining “above the fray” frustrate you?

JR: Everyday I feel not frustrated, but inspired. We’re bringing in voices everyday About RBG in Rosen's bookRead More

Justice Kennedy received the Medal from Justice Gorsuch, his former clerk, and he reminded us how to respond to all the increasing incivility we see these days. The only way to meet incivility is with civility. The Martin Luther King and Gandhi approach is the only approach. That’s how we see our role.

The Constitution is not set up on the principle of trusting the government. Men and women are not angels. It’s set up to counter the passions of the mob by trusting institutions and placing power not all in one place. We are not in a constitutional crisis, but this is a time of constitutional conflict.

LP: Agreed. But recent events have underscored for me just how dependent the Republic is on mere norms. For example, the Justice Department’s independence of the Executive Branch is really a norm, not enshrined in the Constitution. Do we just need to trust that future elected officials will subscribe to what was once our agreed-upon norms?

JR: The Constitution is not set up on the principle of trusting the government. Men and women are not angels. It’s set up to counter the passions of the mob by trusting institutions and placing power not all in one place. We are not in a constitutional crisis, but this is a time of constitutional conflict.

LP: So you’re not as frightened as I am.

JR: I’m not allowed to be frightened or not frightened. But history does remind us that we’ve gone through worse. During the Civil War, politicians were caning each other on the floor of Congress.

LP: You wrote a great piece in The Atlantic last year, headlined “America Is Living James Madison’s Nightmare.” How so?

JR: We are in a Madisonian nightmare. He said we should be ruled by reason, not passion. Factions arise, he believed, when public opinion forms and spreads quickly. But they can dissolve if the public is given time and space to consider long-term interests. He called for “cooling mechanisms”—roadblocks or speed bumps that could slow down the will of the mob. Well, social media has unmanned many of them. Inflammatory speech travels faster than speech based on reason, as Madison told us.

LP: So what is the answer to all the mob noise?

To The Ginsburg TapesListen

LP: Yes, that’s part of the reason we started The Citizen. It feels like we’re awash in more information than ever, but less wisdom.

JR: That’s exactly right. There’s a difference between information and knowledge. Information is discombobulated bits of data that don’t contribute to wisdom. What Madison says to us, what Justice Ginsburg says to us, is that it’s our obligation to achieve deep knowledge. And you get there by deep reading, rather than browsing or losing ourselves on Facebook.

Header photo: U.S. Supreme Court