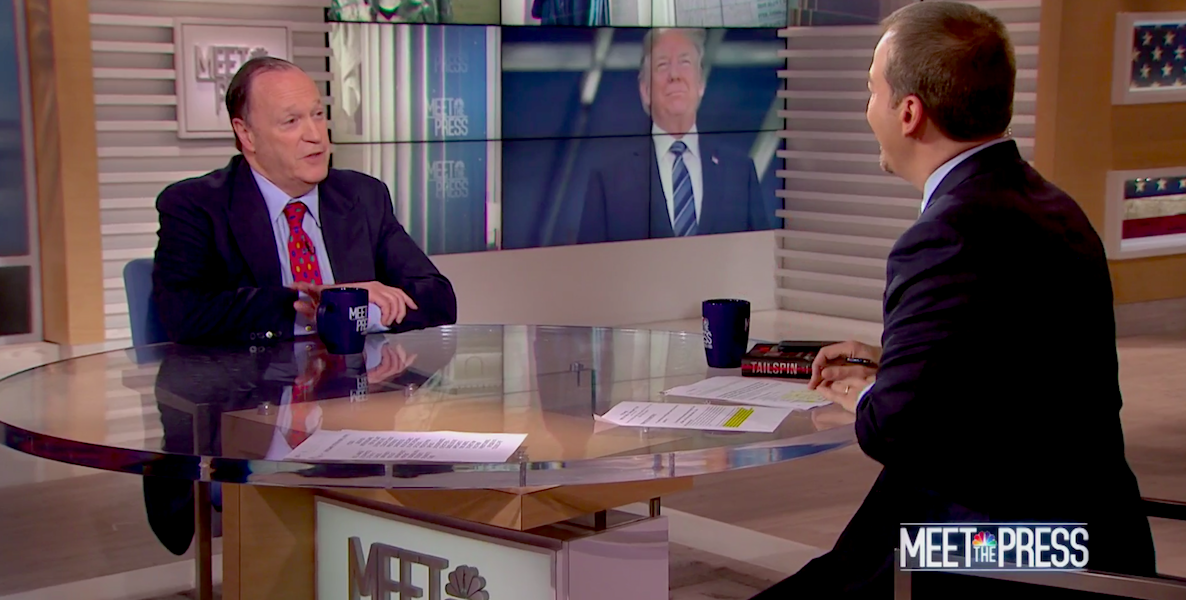

Steven Brill has long been one of the nation’s most thoughtful and provocative thinkers. But he’s also a doer. Brill created American Lawyer magazine, which broke new ground by covering the legal industry like a business, and then launched Court TV. His Brill’s Content magazine held media accountable in the 1990s, when some of us, foolishly it turns out, thought that the national narrative couldn’t get more trivial. His last book, America’s Bitter Pill, remains the best, most maddening descent into the absurdity that is American health care.

Yet when he steps onto The Free Library stage tomorrow night, he’ll be here to discuss his most important work yet. Indeed, Brill’s latest book, Tailspin: The People and Forces Behind America’s Fifty Year Fall—and Those Fighting to Reverse It just might rival Hillbilly Elegy as the most important book of the Trump era for answering the question that has haunted so many of us as we watch cable news or read the daily headlines: How’d we get here?

Tailspin is the best encapsulation yet of, as Brill writes, the “great unraveling of American exceptionalism” these last 50 years. Early on, he makes a compelling case for just how low we’ve sunk, noting that America suffers through “657 water main breaks a day” and that “a child’s chance of earning more than his or her parents has dropped from 90 percent to 50 percent in the last fifty years. The American middle class, once the inspiration of the world, is no longer the world’s richest.”

What follows is a dissection of the forces behind the decline. Brill spares no one, including his own Baby Boom generation. He blames “the polarization and paralysis of American democracy” partly on a “protected” class, a “new aristocracy of rich knowledge workers,” who have no need for government—that’s for the “unprotected”—and who created financial instruments and corporate legal defenses that feed greed and further the divide between the haves and have-nots. I caught up with Brill last week and we started our conversation there: On the death of communitarianism, the increasing lack of a sense that we’re all in this together.

There’s always been a balance that has to be struck between Democracy and a capitalistic free market. That balance now is totally out of whack. The protected class doesn’t need government for anything.

LP: Reading Tailspin made me think often of my father, who was a Cold War Democrat, served his country in uniform, and who, on his deathbed four years ago, said, “I don’t know when paying your taxes became political. In my day, it was just something you did because you were part of a community and you owed it to your neighbor.” Does that resonate with you?

Brill: Absolutely. We always paid for infrastructure through a gasoline tax. That was as American as apple pie, and it happened under Truman, Kennedy, Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter. It was totally non-controversial and bipartisan. The money went into the National Highway Trust Fund, so we could maintain our infrastructure, which was the envy of the world.

The last time we raised the gas tax was 1993. Now, Republicans don’t agree with Democrats on anything, Democrats don’t agree with Republicans on anything, and any tax is immediately off the table. Add to that how so many Republicans are so anti-government, and Grover Norquist’s no-tax pledge, and you get just what your father was talking about.

LP: The disappearance of the common good?

Brill: Absolutely. Look, we’ve always debated this central challenge in America: How much competitiveness and striving for personal success does the free market need, versus how much should we worry about the common good? There’s always been a balance that has to be struck between Democracy and a capitalistic free market. That balance now is totally out of whack. The protected class doesn’t need government for anything. Schools? They send their kids to private schools. Airports? They fly on private jets. National defense is the only thing the protected and unprotected have in common, which is why no one says, “We’re not going to pay a penny more on national defense or to fight terrorism.” Jury duty works now only because we got rid of all those exemptions that the protected class could take advantage of.

LP: You go so far as to make the case that we’ve created a system with so much due process that it impedes progress. I never thought of due process as a bad thing.

Brill: One of the themes of the book is that too much of a good thing isn’t great. The 1946 Administrative Procedures Act, which inserted “due process” into federal regulations, made sense. Let’s make government agencies accountable. Well, that became thousands of lawyers, hearings and lawsuits, gumming up the works.

Think about raising the Bayonne Bridge. Seven years? Zillions of dollars in litigation? A 2,000 page environmental impact study? C’mon, give me a break.

I tell this story of Larry Summers, when he was president of Harvard, stuck in traffic during repairs to the Anderson Memorial Bridge, which connects Boston to Cambridge. They were repairing it for close to 5 years, and he did a little research. Turns out it took nearly five times as long to repair it as to build it. These are the reasons people don’t trust government.

I make the case that Trump is explainable. 46 percent of voters were just so frustrated they said, “Screw it, let’s roll the dice on this guy.” That’s not an analysis popular on the East Side of Manhattan, but go into Harvey County, Virginia and see how bad the trade assistance programs have been.

LP: You also blame college-based “meritocracy” for creating moats that separate the protected from the unprotected. Isn’t meritocracy a good thing?

Brill: We had one aristocracy, wealthy families using connections to get into college, and now we have a new one, of smart, high-achieving people. We now have knowledge workers building those moats. Listen to the Yale admissions director talk about how hard it is to achieve diversity. Well, Amherst and Princeton seem to have figured it out.

LP: Yet, your narrative is ultimately hopeful. You conclude by focusing on the people and ideas that are offering solutions. It made me think that’s the real resistance.

Brill: Yes. Think of the Bipartisan Policy Center. It consists of Democrats and Republicans, they don’t give up their ideals, but they fight them out, compromise, and come up with real policy solutions. These are people who, at first you want to say to them, “You’re crazy—why don’t you get a real job?” But there’s really good stuff coming from them, and their smart policies will be there when the public comes around and demands solutions.

Or there’s the veteran in Queens, New York, who converted a zipper factory into a job retraining site. So that sales clerks who were making $18,000 a year are now making four, five times that coding software.

LP: In that sense, maybe voting for Trump wasn’t as irrational as many of us thought. NAFTA passed in 1993. The Clintons, then, had 25 years to retrain those whose livelihoods would be affected by globalization. Maybe voting against Hillary was payback for just paying that lip service.

Brill: Oh, I make the case that Trump is explainable. 46 percent of voters were just so frustrated they said, “Screw it, let’s roll the dice on this guy.” That’s not an analysis popular on the East Side of Manhattan, but go into Harvey County, Virginia and see how bad the trade assistance programs have been.

LP: Finally, a few months back, you announced News Guard, another entrepreneurial venture of yours that is, I think, much-needed. I couldn’t help but wonder if News Guard is your way of doing what those you profile in Tailspin, like the zipper factory guy, are doing: Offering a solution.

Brill: I’m trying. I’m trying. News Guard is premised on the quaint notion that human intelligence is better than the artificial kind. We’re hiring professional journalists who will survey 7,500 news outlets, making up 98 percent of online engagement in the United States, and will rate them for their reliability —a green dot means it’s generally trustworthy, yellow means it’s inaccurate, and red means the site is deliberately deception. We’ll supplement that with a nutritional label, a longer history of each site’s track record, history and ownership.

LP: It’s a journalistic response to fake news.

Brill: Why just wring our hands about it? Let’s do something.

LP: When will it get to market?

Brill: You’ll be able to download for free a browser plug-in version this summer. Later this year we’ll launch a mobile version.

LP: I can’t wait. Steve, thanks for writing Tailspin, it’s an important contribution.

Brill: Thank you.

Photo via nbcnews.com