The waiting room at Puentes de Salud, a nonprofit health center for Latino immigrants, is buzzing on a quiet Monday night in South Philadelphia. Papel picado decorations and Latin American paintings lines the walls. Carlos, the receptionist, calls the patients one by one into exam rooms, where doctors and nurses diagnose and treat them, for anything from a sprained ankle to pregnancy to diabetes-related complications.

In another part of the waiting room, medical school students are giving a Spanish language presentation about the effects of alcoholism to a group of patients. On other nights, they hold sessions on bike safety, sex education, sun protection and food stamp eligibility.

At the back of the room, a plastic table full of legal resources for undocumented immigrants urges clients: Conozca sus derechos en el trabajo. Off to the side is a community kitchen, where volunteers offer healthy eating classes; elsewhere, there’s a library full of books for youth and a room for yoga, arts and meditation.

“Once you open the door and you admit that they are a real, palpable, part of my community, it’s like driving by a car accident. You’re either gonna stop by and help or you’re not,” Larson says.

Puentes is not officially part of any Philadelphia health system, though it is run and staffed by doctors, nurses and students from medical schools all over the city. Most of those workers are volunteers, serving some of the most vulnerable people in Philadelphia: Uninsured and mostly undocumented immigrants from Mexico and Latin America who cannot afford hospital care, and are often too afraid to seek it, anyway. Almost 100 percent live below the poverty level.

![]()

An HBO documentary released last year called Clínica de Migrantes chronicled the clinic and the work of its staff and leadership. In one scene, a patient named Dacey first visited a local emergency room with a splitting headache. She racked up a bill for $3,856 for two aspirin, acetaminophen, caffeine pills, one urine collection kit, one PET-U visit and one observation. At Puentes, an initial consultation costs Dacey $20; follow-ups cost $10.

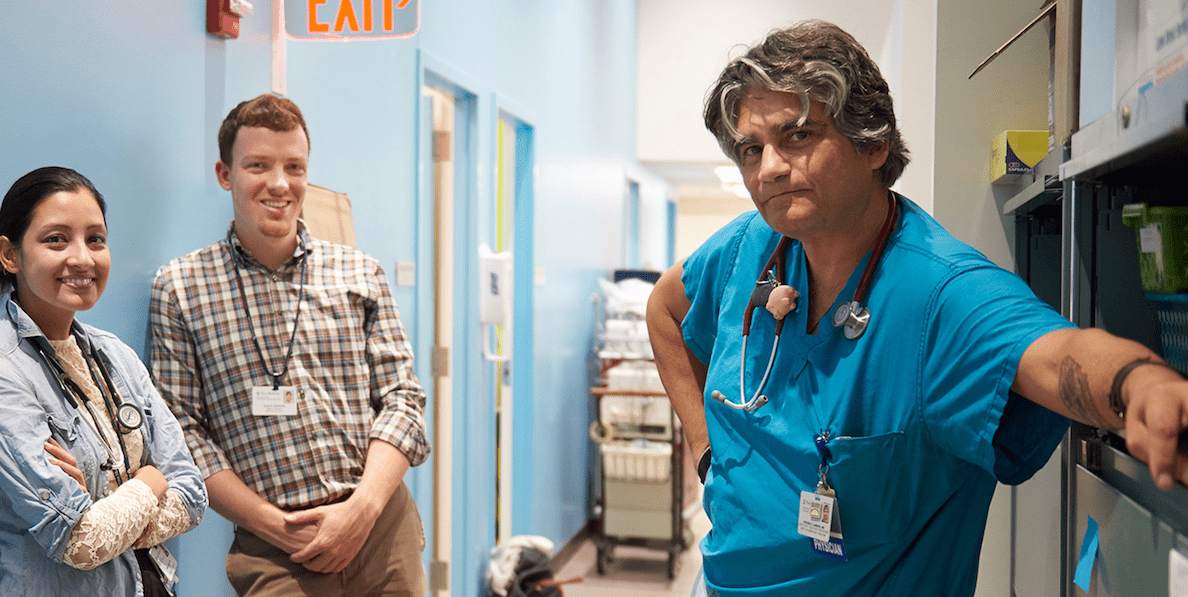

“I’m not here to discuss the politics of this thing,” Puentes co-founder Dr. Jack Ludmir, a Jefferson OB/GYN, says in an early scene. “This is purely healthcare providers and the moral and ethical obligation.”

At the time the documentary was filmed, the nonprofit was just about to move into its permanent location at 17th and South streets, in an abandoned space Penn had donated, after several years spent squatting in the former St Agnes Hospital and local UPHS health centers after hours.

A patient named Dacey first visited a local emergency room with a splitting headache. She racked up a bill for $3,856 for two aspirin, acetaminophen, caffeine pills, one urine collection kit, one PET-U visit and one observation. At Puentes, an initial consultation costs Dacey $20; follow-ups cost $10.

Since then, its clientele has increased between 15 and 20 percent. Puentes now serves around 7,500 clients a year at the health clinic, and through its education and legal programs. The mission is to address not just acute issues, but the underlying social determinants of health, like socioeconomic status, literacy and education level, as well as the political and legal environment. “The better your education, the better your opportunities for jobs, health, and more,” says charismatic co-founder Dr. Steve Larson.

Larson — with a salt-and-pepper ponytail and visible tattoos — cuts an unlikely figure for someone who is also a Penn professor and works in its emergency room. But it’s clear from his every interaction that he cares deeply about the patients he sees at Puentes. Larson, whose mother is Puerto Rican, slides in and out of Spanish, translating for others in the room the experiences his patients convey to him — of bad experiences with other providers around the city, where they have been denied treatment or slammed with bills they cannot pay.

Many of them, like Dacey, talk about being far away from home and struggling to survive uninsured and undocumented. “Once you open the door and you admit that they are a real, palpable, part of my community, it’s like driving by a car accident. You’re either gonna stop by and help or you’re not,” Larson says in the film.

Like many of its patients, the inspiration for the organization’s multidisciplinary approach comes from Latin America. Larson learned about community-centered medical practices while visiting Central America for work during the 80s and 90s. Back home in the United States, he connected with undocumented immigrants in 1993, at Kennett Square’s Project Salud, which primarily serves migrant mushroom workers.

At the time the documentary was filmed, the nonprofit was just about to move into its permanent location at 17th and South streets. Since then, its clientele has increased between 15 and 20 percent; it now serves around 7,500 clients a year at the health clinic, and through its education and legal programs.

Larson started Puentes with Ludmir and primary care Dr. Matthew O’Brien, who now teaches at Northwestern University. The doctors had been frustrated by continuously seeing patients with preventable problems landing in the emergency room and reached out to South Philly barrio leaders, who helped them craft a program to address the health and other needs of Latino immigrants.

Those immigrants are the city’s poorest, according to a study by the Pew Charitable Trusts, with 37.9 percent of Philly Latinos living under the poverty line. There are 50,000 undocumented immigrants in Philadelphia, many from Latin America, who are generally ineligible for Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act. Many don’t speak English, which makes the already complicated American healthcare system more difficult to navigate.

![]()

Sometimes, immigrants are eligible to receive care through Pennsylvania’s Emergency Medical Assistance program. But when patients don’t get this kind of rare government support or simply can’t foot the bill, Puentes will pitch in. Since the organization doesn’t receive or rely on federal or state funding, Larson and the rest of the Puentes leadership has to raise almost $1 million a year.

The last few years have been the toughest for Puentes clients, many of whom live in fear of la migra. “Our [patient] volume has exploded. Many people are fleeing other cities like New York, Baltimore … And they are coming here,” says Annette Silva, the community liaison nurse. “At Puentes, they feel safe, and they feel safe in Philadelphia.”

Puentes partners with Justice at Work, a nonprofit that provides legal counsel to low-income and immigrant workers, to help patients advocate for themselves and improve their working and living conditions, and address any concerns from doctors when they see bruises or injuries that look like abuse. Legal considerations have become more difficult under the Trump administration’s immigration policies.

“Political changes have had a change,” says Monica Posada, one of two behavioral consultants and psychologists who offer support and counseling to patients with mental illness, addiction, and trauma. “When there was notice that Trump was going to be president, there was an impact, because a message was being sent against that community.” Even now, the Colombian native notices spikes in stress and anxiety every time a new policy comes out. “Children are afraid of being separated from their parents,” she says.

But despite the turbulent and anti-immigrant political climate, Puentes de Salud keeps its doors open. And Larson says it will continue to grow all of its programs, to give the clinic’s population the tools be healthy and thrive in Philadelphia. “We don’t have a lot of resources,” he says, “but we use them wisely.”

![]()

MORE ON PHILADELPHIA’S LATINX AND HISPANIC COMMUNITIES