A few weeks ago, SEPTA announced a new pilot initiative, SEPTA Key Advantage, that has the potential to transform the transit agency’s business model in exciting ways that could stabilize local transit funding.

If SEPTA’s board votes to approve Key Advantage as a permanent initiative this spring, the agency will be looking at improved service, restoration of ridership lost during the pandemic — and an employee benefit for tens of thousands of our region’s workers.

The operating idea behind this new initiative is the concept of the “institutional pass.” Institutions will buy passes in bulk from SEPTA and make these passes automatic employee benefits. As a result, SEPTA will be able to offer those institutions a bulk discount.

Thanks to the new SEPTA Key Advantage program, getting more fare revenue doesn’t have to mean raising base fares on the backs of riders.

The initial pilot will include three large employers: Penn Medicine, Drexel University and Wawa. Beginning May 1, about 15,600 workers will be eligible to receive discounted, employer-paid monthly Anywhere Passes for a six-month trial period.

This is a win-win-win for SEPTA, employers, and anyone interested in transit’s success and growth.

- SEPTA’s win: more certainty about medium-term revenue and increased ridership.

- Participating institutions win by being able to offer workers a popular and affordable new benefit, just as recruiting and retaining talent (and bringing employees back to offices) have become more difficult. Participating institutions, especially Drexel, could also reasonably justify mothballing aging parking assets.

- The broader public wins a more stably funded transit system that’s less vulnerable to federal and state political shifts and better able to expand service. Other positive outcomes could include less traffic on our roads and more support for local economies, thanks to those returning-to-office workers.

Still, this test run will be open to Penn Medicine, Drexel and Wawa only. It’s structured as a pilot because SEPTA General Manager Leslie Richards can create permanent programs only with board approval. So far, there’s no sign of board resistance to extending Key Advantage past the initial six months, but, if approved, it will likely be early fall before new institutions can sign on.

According to unnamed sources, there’s been considerable interest from companies reaching out to SEPTA since the announcement. Some were allegedly miffed at not being invited into the first-round cohort. The limiting factor for the program’s growth, at least in the short-term, may be SEPTA’s ability to scale up administrative capacity to handle all the contracts. These are great problems to have. Luckily for us all, SEPTA has a very smart, capable team of staffers on the case.

It started with college students

Conversations at SEPTA about an institutional pass concept began in 2013 and 2014. Back then, the idea was to create bulk fares for university students using Pittsburgh’s successful university pass program as a model. SEPTA’s pilot, however, will not include college students, even though Drexel University itself is part of the initial trio.

The unofficial plan at SEPTA is to branch into student passes in a future phase. As it turned out, new employee benefits were relatively faster and more straightforward to stand up than new student benefits.

But advocates who have long worked to advance the university pass concept within SEPTA — an effort that I have been closely involved with from 2014 through the present day — are not disappointed by this outcome. Instead, they are thrilled with the pilot’s progress among those three large employers.

The main supporters of student transit passes have included SEPTA’s Youth Advisory Council, 5th Square, the Clean Air Council and the Transit Forward Philly coalition, who worked with staff allies at SEPTA to overcome internal resistance and neutralize arguments that had long prevented the concept from advancing.

We can have a city where most people have their transit costs covered in a way that is invisible to them, through their job or their place of residence, making transit feel free to the pass-holders and encouraging more use of the region’s transit network.

These transit advocates and transportation environmentalists were inspired by success stories from Pittsburgh, Seattle, Chicago, Washington DC, Columbus, Ohio, and other cities. Greater Philadelphia possesses key ingredients. Not only do we have more higher-ed institutions, we also have a more expansive regional public transportation network than many other university pass cities. It became clear to these groups that a pass like Pittsburgh’s U-Pass could be even more successful here.

SEPTA could add a truly massive number of transit riders by putting a monthly pass into the hands of every college student and university worker, from custodians to administrators to professors. According to Campus Philly’s most recent annual report (2019), enrollment at their partner schools in our region was over 278,000. Add in university workers, and there’s a major opportunity for growing transit ridership and revenue.

For various reasons, the student pass idea on its own generated socializing and beginning analysis — but not much action — from SEPTA under the administration of then-General Manager Jeff Kneuppel.

The momentum for change

A key moment came in 2020 when advocates were able to secure, with the support of then-brand-new GM Richards and her team, a small grant from the American Public Transportation Association (APTA) to produce original research on applications for institutional transit passes for large employers, university students and workers, City government and residential apartment buildings.

SEPTA brought more funding to the table and contracted with Econsult to create a financial model to explore the possibilities with more rigor. This was a key step: Until that point, the financial viability had been a sticking point for advancing such a program. Financial analysis was able to clear away some of the internal barriers to SEPTA putting forth a concrete proposal. The pandemic’s impact on revenue and ridership also played a catalytic role in increasing interest among SEPTA management.

Another important piece of context has been the very fluid situation around federal emergency support for transit. Also, starting this year, scheduled changes to PA transit agencies’ revenue stream could make state funding — SEPTA’s largest revenue source — less predictable. Decision-makers’ desire for a new, stable local revenue source that can be used in flexible ways increased greatly during the pandemic.

Now that there’s a framework for institutional passes in place, the sky’s the limit for where this concept can go next.

SEPTA has a lot of ambitious service improvement projects and infrastructure plans in the works, but the question of how frequently they can run the trains and buses really comes down to the size of the agency’s operating budget — and a large portion of the operating budget now comes from fares.

Large and medium-sized employers are the tip of the spear, but bulk-fare boosters have a vision of covering many more populations too, not just university students, but also municipal and School District workforces and residents of multifamily residential buildings. We can have a city where most people have their transit costs covered in a way that is invisible to them, through their job or their place of residence, making transit feel free to the pass-holders and encouraging more use of the region’s transit network.

In that future, with SEPTA receiving a larger and more predictable amount of local revenue in big chunks from all these different sources, the agency would also be better positioned to increase service frequency, expand service to more places, or support targeted fare cuts like fare-capping, additional free transfers, or fare parity between regional rail and transit fares within city limits

There are complementary changes very much worth pursuing too, like introducing a new free or discounted low-income transit pass, ideally paid for by state government for transit agencies across Pennsylvania, or by making the school pass for public school students aged 12 to 18 universal, rather than limiting it to students who live farther than 1.5 miles from school.

These changes, combined with the existing free transit pass for seniors 65 and over, and the recent policy change making transit free for kids under 12 in the company of a fare-paying adult, would complete the safety net for transit, ensuring that someone’s ability to pay isn’t an obstacle to accessing public transportation.

Why not a free pass for all?

The news about the institutional pass pilot, which was described in the press as a “free” pass for the three companies’ workers in many of the headlines, led some observers to question why we shouldn’t just make transit free for everybody and pay for it with state or city tax dollars instead. Free transit as an idea has an alluring simplicity to it that resonates more deeply with some than the vision of bulk fares everywhere. But there’s a fundamental disconnect with this premise in that bulk fare deals create new money for SEPTA, while making transit free at point-of-use for everyone costs money — a lot of money.

It’s worth saying that there are important ways that fare-free transit would undeniably have positive benefits, perhaps most in terms of operational efficiency. As just one example, even though a bus has two doors, it’s agency practice to have everybody line up and board only through the front door of the vehicle for fare-collection reasons, slowing everything down. There’s a cost to administering the fare system, and there are also time costs and efficiency costs involved in prioritizing fare collection over ease of use.

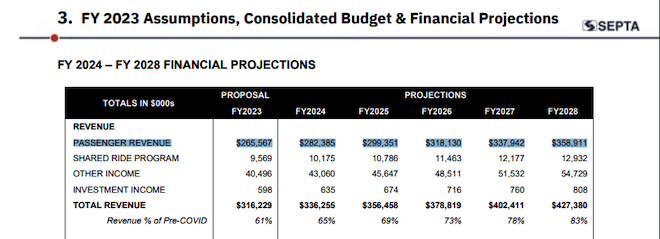

But free transit supporters, though their hearts may be in the right place, are operating with too rosy a picture of the political lift that would be involved in replacing all the revenue from fares for a large system like SEPTA. Before the pandemic, fares brought in around $500 million a year. SEPTA’s new FY 23 Operating Budget proposal now projects that over the next 6 years, fare revenue will bring in $1.86 billion, or around $310 million a year.

For context, the amount of state transit funding currently at risk for the entire state is around $450 million a year, of which SEPTA receives about three-quarters. Keeping just existing funding intact will be a very heavy political organizing lift, but roughly doubling the amount of revenue that SEPTA would need from Harrisburg expressly for the purpose of going fare-free sounds next to impossible, even under the most ideal circumstances.

There’s also a bigger question about whether this is even a good goal to aspire to, even if it were possible for a brilliant organizing campaign to win full replacement of all the fare revenue with state tax money. SEPTA has a lot of ambitious service improvement projects and infrastructure plans in the works, but the question of how frequently they can run the trains and buses really comes down to the size of the agency’s operating budget — and a large portion of the operating budget now comes from fares. Operating funds are the hardest funds to come by, so the problem isn’t just that free fares would forfeit a lot of revenue, but, specifically that they would forfeit a very valuable kind of revenue that is not easily replaceable the way state and federal funding buckets are set up today.

Under the circumstances, there’s arguably an even more compelling equity rationale for a strategy of protecting what fare revenue SEPTA does have, while also trying to increase the amount of fare revenue that SEPTA collects in order to provide better, more reliable service to the transit riders across the region who rely on the agency to connect them to jobs and opportunity.

Thanks to the new Key Advantage program, getting more fare revenue doesn’t have to mean raising base fares on the backs of riders. The agency can build revenue by effectively making the sale to thousands of different institutional partners across the city and region, growing the total pie, while also giving the agency a cushion to make targeted fare cuts for the people who can least afford to pay.

Whether it all works out exactly like supporters envision, only time will tell, but for the moment, it is worth pausing to celebrate sea change at SEPTA, and to appreciate the potential of the opportunity that’s created here.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

![]() RELATED STORIES ABOUT TRANSPORTATION FROM THE CITIZEN

RELATED STORIES ABOUT TRANSPORTATION FROM THE CITIZEN