A few weeks ago, I revisited Seorabol in Olney, the first Korean spot I’d ever experienced. The restaurant, which opened in 2002, is a classic, old-school BBQ joint in what was traditionally Philadelphia’s Koreatown.

The 200-seat dining room, redolent of smoke and roasting meat, buzzes with both families and groups of young people. The place is so big that each table has a button, like a doorbell, to push in order to get the staff’s attention.

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article in CitizenCast below:

![]() The centerpiece of each table is a charcoal-fired grill, where diners sear their own slices of savory-sweet-spicy bulgogi, galbi short ribs and pork belly over the flames, pairing them with rice, gochjang sauce, ssamjang paste, lettuce leaves and little plates of banchan—side dishes of pickled daikon radishes, bean sprouts, braised mackerel, spicy fish cakes and of course kimchi.

The centerpiece of each table is a charcoal-fired grill, where diners sear their own slices of savory-sweet-spicy bulgogi, galbi short ribs and pork belly over the flames, pairing them with rice, gochjang sauce, ssamjang paste, lettuce leaves and little plates of banchan—side dishes of pickled daikon radishes, bean sprouts, braised mackerel, spicy fish cakes and of course kimchi.

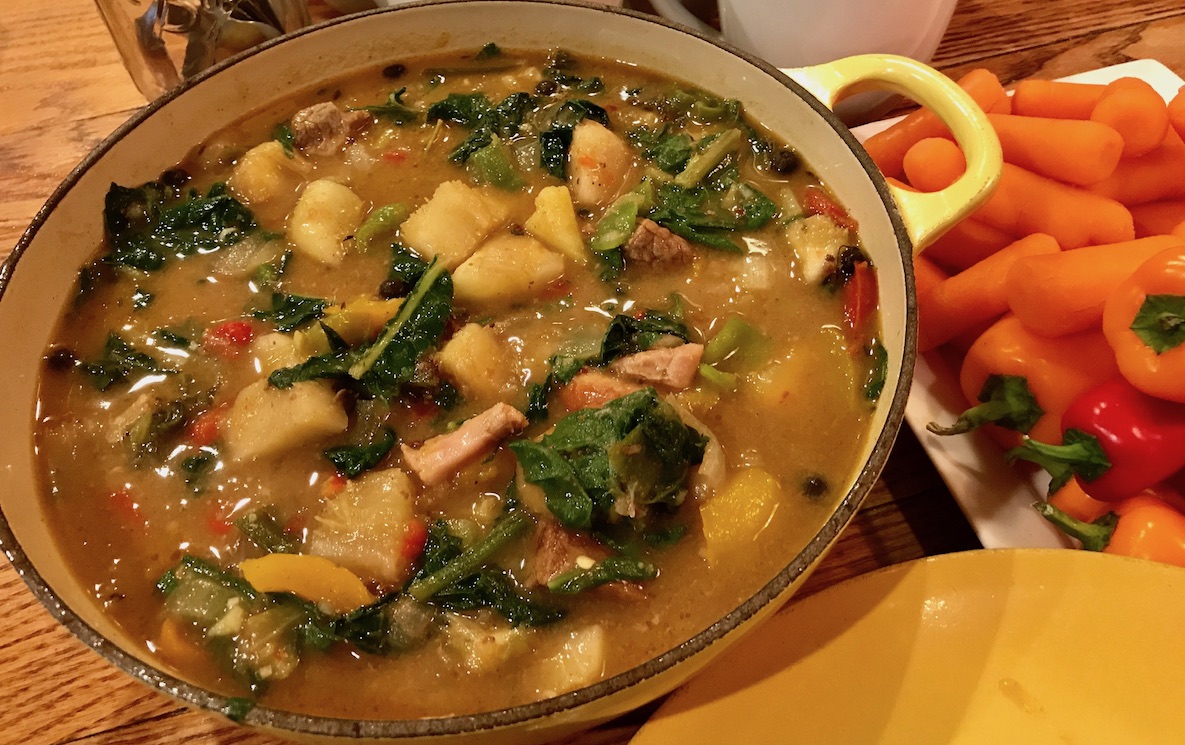

Besides the grilled meat, we enjoyed Seorabol’s excellent pajeon pancakes (especially the hot pepper and the seafood), dolsot bibimbap and a spicy black goat hot pot.

For me, visiting the original Seorabol in Olney was a chance to consider how both the city’s Korean food scene and its Korean community have changed over the past decade.

“It may sound corny, but when I picked up a knife, I felt like King Arthur pulling the sword from the stone,” Cho says.

It’s hard to think of a cuisine that’s risen in popularity more in recent years than Korean food. We’ve quickly seen funky kimchi, hot-stone bibimbap, spicy short ribs and Korean fried chicken become mainstays on countless menus across the country, often served to a K-Pop soundtrack. By 2017, two of GQ’s top 10 restaurants of the year served Korean food.

When the Korean gastropub Southgate opened in Center City in 2015, it was soon followed by Dae Bak, Buk Chon and a number of other options—all opened by younger, second-generation Korean restaurateurs. In fact, Seorabol also opened a new location in Center City last fall, run by 34-year-old Chris Cho, the son of Kye Cho, who first opened Seorabol in Olney.

But a bittersweet irony is happening as modern Korean food proliferates in Center City. In Olney, the old Koreatown has begun to disappear as the next generation of Koreans migrates to the suburbs. One popular barbecue spot Every Day Good House closed in 2018. Kim’s, another Olney mainstay that opened in 1982, has been through changes in ownership.

“There aren’t many Korean places left in Olney,” says Chris Cho, who immigrated here when he was eight years old, at a time when Korean immigrants were among the top 10 foreign-born populations in the city. That has changed over the last couple decades. “Koreans don’t live there anymore. It’s shifted. Back when I was younger, no one lived outside Philadelphia. Now, when new immigrants come, they’re more likely to move to Montgomery County.”

Two of the best Korean restaurants in the region now are Dubu in Elkins Park and Eden in Cherry Hill.

When Cho decided to open up a new location of Seorabol in Center City, he says he wanted to represent his family’s Olney traditions. “Every other Korean restaurant in Center City was fusion or for American tastes,” he says.

![]() Even so, Korean food in the U.S. has been somewhat less Americanized than other Asian cuisines. As Matthew Robard, author of the cookbook Koreatown, U.S.A. told Serious Eats, Korean food is still “unspoiled” with mass-appeal dishes such as pad Thai or General Tso’s chicken. “The food wasn’t marketed at all,” Rodbard said. “They didn’t have to make the egg roll or something like that to fit in.”

Even so, Korean food in the U.S. has been somewhat less Americanized than other Asian cuisines. As Matthew Robard, author of the cookbook Koreatown, U.S.A. told Serious Eats, Korean food is still “unspoiled” with mass-appeal dishes such as pad Thai or General Tso’s chicken. “The food wasn’t marketed at all,” Rodbard said. “They didn’t have to make the egg roll or something like that to fit in.”

However, Cho, like other Korean restaurateurs opening downtown, hit a snag: City officials and landlords haven’t been keen on having open flames in Center City dining rooms. So for now, Olney is still where you have to go for true Korean barbecue.

“If my aunts and uncles came to America and I charged them for banchan, they’d be like, ‘What is going on?’ It would be like charging for a pickle,” Cho says.

Despite the obvious lack of charcoal grills, the menu at Seorabol in Center City is full of greatest hits from the original—it’s just that the galbi and bulgogi are cooked in the kitchen. One dish that Cho prides himself on is budae jjigae (“army stew”) that’s a spicy, pungent, edgy hot pot mingling kimchi, gochugaru chiles, and a mix of tofu, sausage and beans. Cho also has a more expansive drinks menu, focusing on numerous expressions of soju, Korea’s favorite distilled spirit.

Cho says one thing that separates Seorabol from other Korean spots is that he always serves traditional banchan, the complimentary side dishes served alongside the meal. Some modern Korean places charge for the banchan, or skip it altogether. “If my aunts and uncles came to America and I charged them for banchan, they’d be like, ‘What is going on?’ It would be like charging for a pickle,” he says.

“I want more people to know about Korean food,” he adds. “In Philadelphia, no one was paying any attention to Korean food five years ago.”

In fact, not too long ago, Cho wasn’t paying much attention to food at all. Although he’d grown up in the Seorabol kitchen, he was busy running a marketing agency, selling cell phones and flipping houses. “My parents never wanted me to be a cook,” he says. “Korean parents do not want their kids to be cooks.”

Then, one day, family duty called. “My dad got sick and had to go to the hospital, so I started helping in the kitchen,” Cho says. “It may sound corny, but when I picked up a knife, I felt like King Arthur pulling the sword from the stone.”

But Cho’s ambitions—as might be obvious from his YouTube channel—are much different from his father’s. He talks about opening even more locations of Seorabol, and mentions Han Chiang, the ambitious owner of local Szechuan empire Han Dynasty, with nine locations in three states, as a model for expansion. “I’m a Philly guy,” he says. “But there’s only so much we can do in Philly.”

Meanwhile, at the Seorabol up in Olney, in a disappearing Koreatown—at what is still one of Philadelphia’s must-visit restaurants—Cho’s family still keeps traditional charcoal grills lit.

Jason Wilson is The Citizen’s 2019 Jeremy Nowak Fellow, funded by Spring Point Partners, in honor of our late chairman Jeremy Nowak. He is the author of three books, including the recent The Cider Revival, series editor of The Best American Travel Writing, and writes for the Washington Post, New York Times, New Yorker and many other publications. You can find him at jasonwilson.com.

Header photo of Chris Cho courtesy @phobymo