If you have ever wrapped a pregnancy test in half a roll of tissue before throwing it away (privacy, yo!), or if you have ever wished for a better, faster breast pump, or if you have struggled to dig in the garden with arthritic hands, then you are someone who might be able to understand how a single product—say, a flushable pregnancy test, a breast pump with a compression component, or assistive gardening gloves that make it easier to manipulate tools—can change your life for the better. Sometimes, for the way better. And sometimes, lots of lives for the way better.

Changing lives, or at least moments in lives, is part of what drives Sarah Rottenberg, who is something of a one-woman innovation hub at Penn. She’s an adjunct associate professor in the Weitzman School of Design; she’s the executive director of the Master’s in Integrated Product Design (IPD), a School Of Engineering program that intertwines engineering with design and business; and she’s the faculty director and one of the founders of the Executive Program for Social Innovation Design (XSD), which debuted in 2019 as a certificate program for professionals, a collaboration between the Weitzman School of Design and the School of Policy & Practice. (More on that later.)

Changing lives, or at least moments in lives, is part of what drives Sarah Rottenberg, who is something of a one-woman innovation hub at Penn.

These creations—the pregnancy test, the pump, the gloves—are but a few examples of the brilliant inventions from students in the IPD program, which aims to teach a new generation of entrepreneurs, inventors, innovators and designers how to develop products and experiences that address the real needs of real people.

Very few people understand the way to use design thinking—or understand the people they’re designing for—as well as Sarah Rottenberg, says Roy Rosin, chief innovation officer for Penn Medicine. The philosophy of “human-centered design” relies on a deep empathy for the population for whom you’re designing. And long before it was a buzzword and well-established pillar of the innovation world, Rosin says, “Sarah already just lived it and breathed and got it.” And not only that, he says, but “her students are incredible, and she teaches them so well. They really get it, too.”

So what does “getting it” look like, in terms of impact? For starters, it looks like the wearable device Rottenberg’s students designed to help surgeons communicate with one another for more successful surgeries. And it looks like an updated take on the menstrual cup, created (again by students) specifically for athletes who needed something more reliable than what was out there. It’s an IPD/CHOP collaboration to develop better information-sharing between clinicians and patients, and it’s an IPD project with the nonprofit CraftNOW that used design-centric research to create an infrastructure for getting more Philly kids arts- and-crafts education.

It’s also, yes, the aforementioned flushable pregnancy test, which is a story that makes for a good window into IPD, into Sarah Rottenberg herself. Several years back, IPD students Bethany Edwards and Anna Couturier-Simpson were interested in making plastic pregnancy tests more sustainable. Once they began really researching their design demographic, as Rottenberg tells it, they came to realize that many women had a need for more privacy in their tests, too—that for a range of reasons, they didn’t need anyone finding a pregnancy test in a trashcan.

RELATED: Philly-made fruit-hacking tool fights food waste and saves farmers money

So they designed an effective, eco-friendly and flushable test, which they named Lia—a product Rottenberg believed in so much that she actually joined up with the students in 2014 as an early co-founder of Lia Diagnostics, which officially debuted in March. (Headquartered on Chestnut Street, they’ve faced enough demand that they’re currently out of stock.)

The thing about that pregnancy test, Rottenberg says, is that it was a design for “a small moment but a huge moment.” And if they can make moments like that better, and make them better over a lot of criteria in terms of what better looks like … well, you can see how there is a cumulative effect of examining human moments and human needs in search of a solution you can design.

“I think we’re making these small differences,” Rottenberg says—you know, moment by moment, need by need, person by person, product or experience or service at a time. “And they add up.”

Design is everything

When you’re thinking about the people whose perspectives and work can make effect positive change—which is exactly what we here at The Citizen are doing with Generation Change Philly, our ongoing series in collaboration with Keepers of the Commons—it’s easy to overlook the world of design and engineering. For that matter, it’s easy to overlook the role designers play in our lives, just generally speaking. Rottenberg herself even gently jokes: “I mean, I’m not making national policy, peace in the Middle East. I’m not making that kind of product.”

Truth is, though, design is a part of our every waking moment, so ubiquitous that we don’t notice it. But think about it. “You wake up every morning and you get on a bus,” Rottenberg says. “How did you find that bus? How is the bus designed? Then you pass a store: How was that store designed for what’s in it? For you?” From the fork in your hand to the shoes on your feet, she says, design is in everything we interact with. And that’s one of the things she gets excited about—the chance “to continually improve things for people who use them.”

Very few people understand the way to use design thinking—or understand the people they’re designing for—as well as Rottenberg, says Roy Rosin, chief innovation officer for Penn Medicine.

This wasn’t always so apparent to her. Through a different sliding door, she might actually be solving for peace in the Middle East, or something in that vein. She had once imagined a very different career, attending Georgetown University for Middle Eastern Studies. After graduation, the Atlanta native took a job with the Israeli Embassy, but once fully enveloped in the world of global politics and government, she found that the work felt too “detached” from the daily lives of people. She pivoted and went to the University of Chicago for a master’s degree in social science, focusing mainly on anthropology. After that, she followed a path that took her into design research and strategy, and innovation consulting.

“I just loved the work of delving into people’s lives, and also the idea that you could leverage what you learned about people to help make better products and services for them,” she says.

After moving around the country a bit, Rottenberg and her husband eventually decided to settle back in his hometown—Philly. Fast forward a few years, and a teaching gig in design at Penn grew into the opportunity to run the IPD program, which she’s done now for just over a decade, in addition to her teaching. She loves it, and you can see exactly how her background in anthropology and research (and maybe some of the diplomacy, she semi-jokes) come into play: Understanding people at their core is central to her work. Empathy, remember?

RELATED: Philly’s innovation team wants to turn City Hall bureaucrats into problem-solvers

“Some of the biggest problems people need solutions for are things people can’t articulate,” Rosin says. “Sarah understands how to get these things out of people, these things they can’t articulate.”

This is true, says Adriana C. Vázquez Ortiz, IPD alumna and co-founding CEO of Lilu, a company that debuted in 2019 with the “massaging” breast pump that Vázquez Ortiz dreamed up and designed with her co-founder, Sujay Suresh Kumar, as her master’s capstone project. Vázquez Ortiz, who calls her time in IPD “transformative,” says that not only has Rottenberg’s emphasis on user research been a helpful foundation in her own business as they innovate and design new products, but also that her example as a woman in this space was important.

“You hear about not enough women in STEM or STEAM, and not enough women founders, or money for women founders,” Vázquez Ortiz says. “This hasn’t felt like the case for me.” There was Rottenberg, “a strong woman,” the head of IPD. There was Lia. There were her female cohorts, and there was, in a class of something like 16 people, two or three product ideas in women’s wellness, she says.

“I think Sarah made it really normal to innovate for women’s health,” Vázquez Ortiz says. “I’ve never had any doubt as a product designer or engineer that women’s health was important, but not everyone sees it that way. It was good to have another person who sees that in my world, in this world.”

RELATED: LaunchCode comes to Philly to help build our tech talent system

All of this reminds me a bit of Rottenberg’s TedX talk from 2018, wherein she mentions an IPD partnership with Penn’s Pregnancy Early Access Center (PEACE) and Penn Center for Health Care Innovation. Students researched a large but often silent, underserved demographic—women suffering miscarriages—and designed a set of cards aiming to help this audience process feelings, speak to doctors and communicate with loved ones after a miscarriage, things that had proven to present real challenges and fraught moments to significant numbers of patients and their families. Design, Rottenberg told her audience, has the opportunity to transform difficult or even shameful moments “into dignified ones.”

It’s true, Rottenberg admits, she does tend to push students to look at moments “we typically look away from.” And if she has a “slight bias” toward examining the private, the under-examined, the unexplored? Well, surely some of that is the anthropologist in her. Or maybe it’s what Rosin calls her talent for “need-finding.” Then again, she’s also an entrepreneurial type, and isn’t it often the hardest things to talk about that create our most pressing problems? Or, in startup speak, the “pain-points.”

“I think Sarah made it really normal to innovate for women’s health,” Vázquez Ortiz says. “I’ve never had any doubt as a product designer or engineer that women’s health was important, but not everyone sees it that way. It was good to have another person who sees that in my world, in this world.”

Still, not every student or project in the IPD world delves into such deeply personal territory: Rottenberg points to a list of award-winning new products she’s seen come out of the program that don’t live in the “unmentionable” spaces she’s drawn to, from Hideaway, a kitchen table that opens to transform into a full-fledged work space (obviously an answer to work-from-home needs, especially if you live in a tiny Philly rowhouse!), to Rhea, a chair cushion designed for pregnant people who experience pain from sitting in an office chair all day.

In any realm, it’s a truly engaging gig, Rottenberg says. She likes the diversity of the ideas, the diversity of the students, exposing them to new perspectives, examining the role of humility in design, and the excitement of seeing the start-ups and students “just putting new things into the world.”

Creating an ecosystem of human-centered innovators

She doesn’t have an exact count of startup founders with roots in the program but Vázquez Ortiz describes a Philly start-up ecosystem just blooming with IPD grads: interns and founders and early-stage startup players. When she and Suresh Kumar were at the hard-tech accelerator HAX, for instance, there were at least three other startups there with IPD grads, she says, including Wazer (waterjet cutters) and Vue (smart glasses). Not to mention the number of alumni who’ve collaborated with other Penn folks in, say, health or engineering, or joined other new startups, or went to work with design teams at big firms.

The numbers don’t seem to be terribly important to Rottenberg, who instead brings up a team of IPD alumni who are currently working on ways to make OTC healthcare more sustainable. “They got together with a bunch of other alumni as well as current students, and they were all just talking to each other, and building on each other’s ideas,” she says. “And that, to me, is really exciting: It’s about people we need to have living and working in the city, creating this community here and throughout the world.”

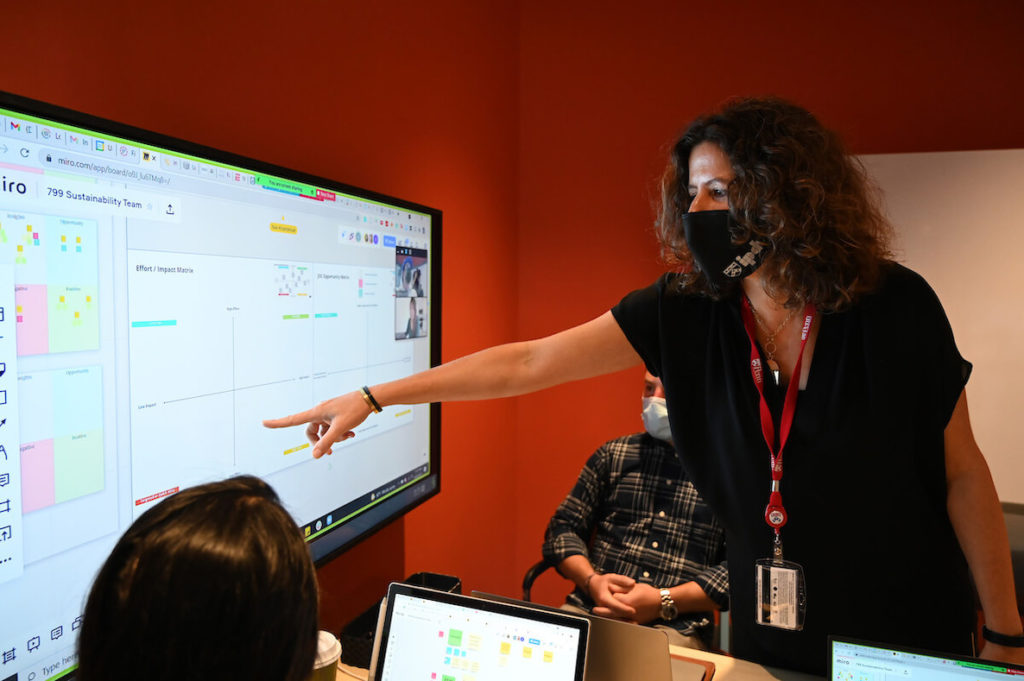

That community is growing. The XSD program, which teaches professionals from architects to nonprofit managers to urban planners (and beyond) how to use design-thinking as a way to make social change, has been such a success that Rottenberg and her colleagues are brainstorming other potential certificate programs that could reach even more people. Meantime, IPD’s move to a more expansive home inside Wharton’s brand-new, cutting-edge Tangen Hall has meant that instead of the original capacity for 40 students total in the program, they’ve been able to expand to 80.

RELATED: “New Futurists” have the talent and drive to make their visions a reality

This is a great thing for Rottenberg, not just from her perspective as a director of a flourishing academic program, but as a researcher and problem-solver set on nurturing more problem-solvers to do their thing, as a thought leader who sees limitless potential in combining all this disciplines with empathy with humility with people and their ideas.

“I also just feel really lucky,” she says. “I get to learn about all these different things.” So many different things: Over the course of just this past year, she’s seen a team of students looking at fertility and egg freezing, another team looking at eating disorders, and another looking at helping wildland firefighters boost their effectiveness on the job.

And so you can understand where she’s coming from. Who wouldn’t want to see so many bright minds engage with these worlds? Or with any world, really, where there are problems to be solved, and solutions to be designed.

The Philadelphia Citizen is partnering with the nonprofit Keepers of the Commons on the “Generation Change Philly” series to provide educational and networking opportunities to the city’s most dynamic change-makers.

![]()

MORE GENERATION CHANGE PHILLY PROFILES

Generation Change Philly: The Intergenerational Poverty Buster