to this story in CitizenCastListen

So…crisis averted, right? Despite the delay between infraction and the imposition of accountability, in the end, justice was served, no?

Well, only in the most superficial of ways. Yes, action was taken and Muhammad was jettisoned. But does the playing out of that most familiar script actually constitute civic progress? Was there any true dialogue or engagement here, or have we just gone through another one-two step of outrage followed by banishment, as has become cancel culture’s norm?

Before getting into it, let’s review the facts.

On social media, Muhammad posted a cartoon of a large-nosed Jew pressing his hand down upon a darkened, huddled mass of faceless people. Next to it was a quote attributed to a French philosopher that was really mouthed by an American neo-Nazi and white supremacist who, just to complete the ignominious trifecta, is also a convicted child pornographer: “To learn who rules over you, simply find out who you are not allowed to criticize.”

Muhammad’s post ran alongside photos of three pop culture figures who had uttered similarly anti-Semitic sentiments: Eagle DeSean Jackson, rapper Ice Cube and TV host Nick Cannon.

Muhammad’s message harkened back to Protocol of the Elders of Zion bile from the early part of the 20th century, which advanced the myth of a nefarious Jewish plan for global domination in an attempt to focus blame for Russia’s economic woes on Jews, rather than on its Tzarist regime. It’s a false meme that has time and again refused to die through the years; its promulgators have ranged from Henry Ford to Louis Farrakhan.

Be part of the solutionDo Something

Now, as a First Amendment absolutist, you’ll rarely find me calling for anyone to be cancelled for expressing a thought, no matter how odious. But Muhammad disqualified himself from leading the NAACP long before his toxic post, and not because of what he said so much as what he did: Seeming to sell out his own constituency.

Back when then-Mayor Michael Nutter tried and ultimately failed to institute a soda tax, Muhammad’s NAACP stood in opposition, arguing that it was a regressive tax disproportionately affecting African Americans.

When Kenney proposed virtually the same tax, the NAACP surprisingly flipped; in short order, it came to light that Kenney’s Political Action Committee had paid one Rodney Campbell $45,000 in 2017.

Turns out, Campbell was Muhammad’s name before his conversion to Islam. (All told, Kenney’s PAC has paid Muhammad, née Campbell, a reported $95,000 through the years, which may have something to do with Kenney’s original reticence in calling for Muhammad’s resignation after the anti-Semitic posting.)

Muhammad lost the ethical standing to lead a storied brand like the NAACP the moment he appeared to be hiding payments from Kenney’s PAC by accepting them in his former name; nothing illegal, mind you, but the secrecy hinted at consciousness of moral guilt.

So, for me, the issue of Muhammad’s continued employment is besides the point. Muhammad is now gone from Philadelphia’s public stage, but the ideology he’s put out there has long been proven to have legs.

The emphasis ought to have been not on firing Muhammad, but answering him.

Last week’s summit between Black and Jewish leaders had the potential to do just that. It began in inspiring fashion, with Bishop Louis Felton, pastor of Mt. Airy Church of God in Christ and vice president of the local NAACP, addressing what he called the elephant in the room.

“If no one else says I’m sorry, then I’ll say it,” Felton said. “I’m sorry that there was no immediate action taken between respective organizations. I’m here in pain, because I know my brothers and sisters are hurting.”

Felton’s moving comments amounted to an act of stirring civic leadership, but in his, and virtually everyone else’s, understandable rush to move beyond the pain caused by Muhammad, the dialogue morphed into a series of vague generalities rather than much-needed uncomfortable engagement.

There is, after all, a fissure between Blacks and Jews, two groups once aligned together on the front lines of the civil rights movement. And, in the dialogue last week, there were ample opportunities to lay it all out on the problem-solving table.

For example, Rev. Cleveland Edwards, second vice president of the NAACP, observed that he’d gone to Overbrook High School back in the day, when it was “60-percent Jewish…we got to understand each other.”

That prompted Rabbi Eric Yanoff of Merion’s Adath Israel: “Pastor, I bet you went to high school with several people who are now a part of my synagogue because we joined together with another synagogue about 12 years ago which was in the heart of Overbrook and so we have people in common, we all have people in common, that’s what it means to be family.”

It was a sweetly smiling exchange and a feel-good moment, but it was devoid of any attempt to reckon with the very history it raised. Those congregants now on the other side of City Line? They were there largely thanks to white flight, which was fueled most prominently by the excursion of Har Zion Synagogue from Wynnefield to Penn Valley.

Among Blacks of the hip-hop generation, those old tropes about Jewish “globalism” and power seem to be taking on new currency, in part because of the extrapolation of the personal to the cultural—if you grew up with Jewish landlords who lived in the suburbs, you might be predisposed to tales of Jew as economic oppressor—and in part because we just don’t know that much about anything, anymore.

So let’s try and answer Rodney with some facts, shall we?

First, every story that points to a crack in Black and Jewish relations regurgitates the old standbys, as I have done in the past: That was, after all, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel linked arm-in-arm on that Selma bridge with Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., whose first among equals social justice soulmate wasn’t Andrew Young or Rev. Ralph Abernathy, but Stanley Levison.

Henry Moscowitz co-founded the NAACP with W.E.B. DuBois, and Kivie Kaplan of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations was its president from 1966 to 1975. Philanthropist Julius Rosenwald underwrote more than 2,000 primary and secondary schools and 20 Black colleges in the middle part of the 20th century; particularly in the South, the “Rosenwald schools” played a key role in educating Black Americans.

But over time the alliance has frayed. There were differences over affirmative action and, especially, over Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians. And there were personal slights that made common ground harder to find, like contentious interactions between Jewish landlords and Black tenants, Jesse Jackson referring to New York as “Hymietown,” and Louis Farrakhan’s hateful rhetoric, which has included calling Jews “termites.”

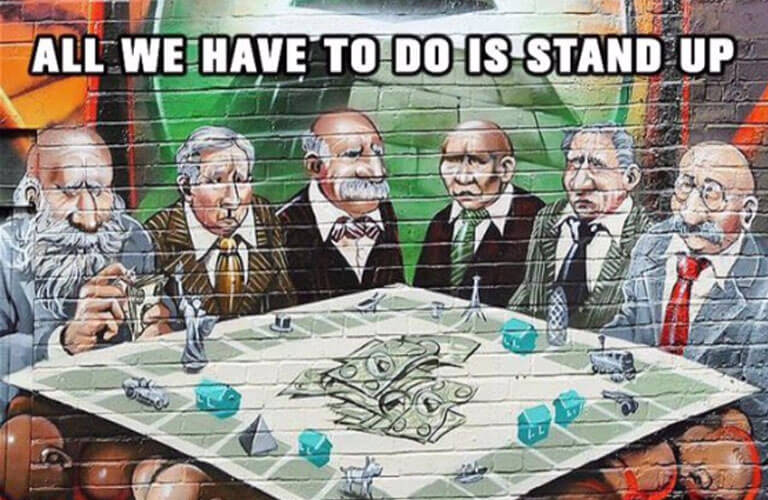

And now, thanks to social media and a widespread lack of knowledge of our own history, tinfoil-hat conspiracy theories suggesting Jews actually orchestrate Black oppression suck in the likes of influential Black leaders like Muhammad, Jackson, and Ice Cube, who recently posted this horrible meme:

But it’s also true that, even now, more than any other group, American Jews have had the backs of African Americans in the pursuit of justice. It was 25 Jewish members of Congress last December calling for the dismissal of Trump whisperer Stephen Miller, when his white supremacist emails came to light. And it is the reform movement of American Jewry—by far the biggest contingent of American Jews—that has endorsed reparations for the descendants of slavery.

Real dialogue will start once African Americans acknowledge these and other Jewish contributions to social justice, while Jews cop to where they’ve come up short: White flight, opposing Affirmative Action, tacit acceptance of subjecting Palestinians to the modern equivalent of passbooks.

Most of all, the two groups need to come to a meeting of the mind (and heart) on the notion that Jews disproportionately wield economic power to the detriment of African Americans. Understanding Antisemitism: An Offering to our Movement, a report from Jews for Racial & Economic Justice, contains some eye-opening data on this point.

Let’s Take a Look at Those Numbers

First, worldwide, there are only 14 million Jews, which includes roughly 1 million Jews of color. In the States, there are 5.3 million Jews, all of 2.2. percent of the population.

Today, most Jews identify as and are seen to be white, and they benefit from white privilege, as Rabbi Annie Lewis of Temple Beth Zion-Beth Israel acknowledged in passing during last week’s discussion in Mt. Airy. But as Charlottesville showed—“Jews will not replace us!”—one important group most emphatically doesn’t consider Jews to be white: white supremacists. Shouldn’t the old Middle East adage “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” pertain to race relations in the States, as well?

“There is also great class diversity among Jews,” reads the JFREJ report. “The very wealthiest individuals on the planet are predominantly Christian according to non-partisan wealth research firm New World Wealth. In 2015, their study found that more than half of the world’s millionaires identified as Christian and that there are more Hindu and Muslim millionaires than Jewish ones. Of the 13.1 million people in the world who are millionaires, 56.2 percent were Christian, while 6.5 percent were Muslim, 3.9 percent are Hindu and 1.7 percent are Jewish.”

Yes, the report outlines, Jews in the U.S. earn higher incomes than most other religious and ethnic groups; about 25 percent report household income over $150,000, compared to 8 percent of the overall population. But, given how few Jews there are in the States, the same statistics lead to an inconvenient fact if you’re Muhammad, et al: The vast majority of high income people in the U.S. are non-Jews.

And keep in mind, income level doesn’t necessarily imply wealth. “Since the majority of U.S. Jews were poor and working-class immigrants only a few generations ago, looking at inherited wealth would likely reveal an even greater concentration of resources in the hands of elite, white, non-Jewish families,” writes the JFREJ.

About Black-Jewish relationsREAD MORE

All that said, it’s not difficult to understand why Jewish conspiracy theories have a history of catching on among some in the Black community. The roots of Black distrust go way back, spurred by Jewish assimilation.

One of my literary heroes, James Baldwin, brilliantly explained the phenomenon in a 1967 New York Times Magazine essay, headlined “Negroes Are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White”:

In the American context, the most ironical thing about Negro anti-Semitism is that the Negro is really condemning the Jew for having become an American white man—for having become, in effect, a Christian.

The Jew profits from his status in America, and he must expect Negroes to distrust him for it. The Jew does not realize that the credential he offers, the fact that he has been despised and slaughtered, does not increase the Negro’s understanding. It increases the Negro’s rage.

That’s the part of Baldwin’s essay that is most quoted, often in the context of explaining or even justifying Black anti-Semitism. But leave it to ol’ Jimmy to actually come full circle. By the end of his 53-year-old piece, Baldwin pivots:

The ultimate hope for a genuine black-white dialogue in this country lies in the recognition that the driven European serf merely created another serf here, and created him on the basis of color. No one can deny that the Jew was a party to this, but it is senseless to assert that this was because of his Jewishness

All racist positions baffle and appall me. None of us are that different from one another, neither that much better nor that much worse. Furthermore, when one takes a position one must attempt to see where that position inexorably leads.

One must ask oneself, if one decides that black or white or Jewish people are, by definition, to be despised, is one willing to murder a black or white or Jewish baby: for that is where the position leads. And if one blames the Jew for having become a white American, one may perfectly well, if one is black, be speaking out of nothing more than envy. If one blames the Jew for not having been ennobled by oppression, one is not indicting the single figure of the Jew but the entire human race, and one is also making a quiet breathtaking claim for oneself.

I know that my own oppression did not ennoble me, not even when I thought of myself as a practicing Christian. I also know that if today I refuse to hate Jews, or anybody else, it is because I know how it feels to be hated.

How about that appeal to common humanity? It conjures Rabbi Heschel’s observation at the most perilous moment of the civil rights movement: “The redeeming quality of man lies in his ability to sense his kinship with all men.”

"Negroes Are Anti-Semitic Because They're Anti-White"Read James Baldwin's essay

Last week’s discussion at that Mt. Airy church touched on all that history, but way too tentatively. Here’s hoping it was the first in a series of talks that drop the politeness and gets real, like one of those “no holds barred” family fights that you dread, but that you emerge from, more united and in love than ever.

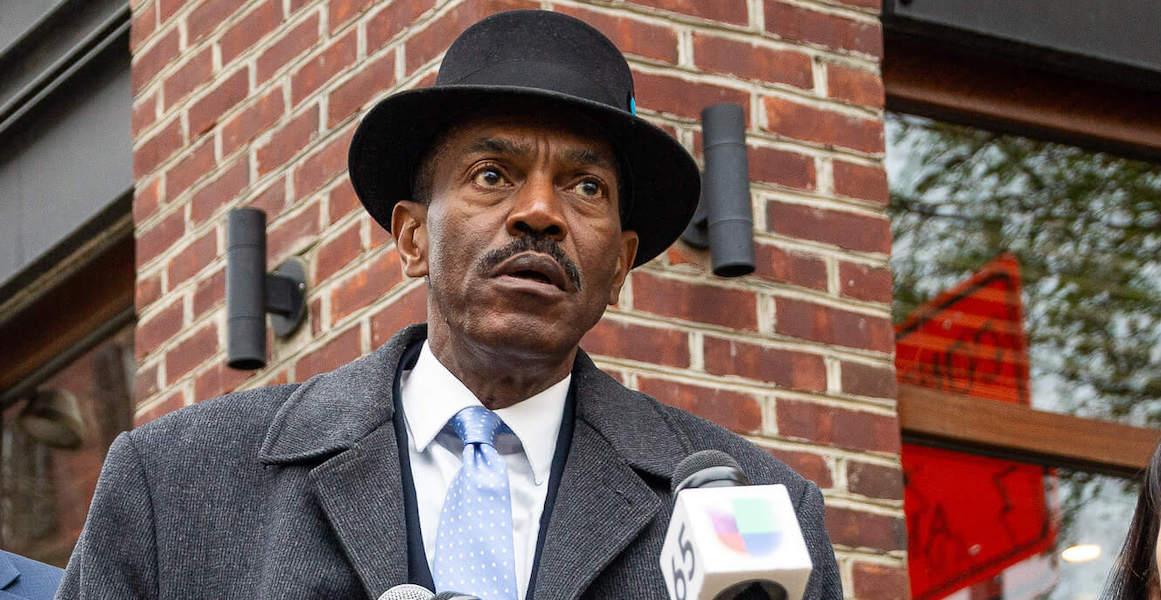

Header photo: Rodney Muhammad speaks at a press conference following the unjust arrests of two Black men at a Center City Starbucks | Photo by Jared Piper / PHLCouncil