Most of us probably remember when the Philadelphia Energy Solutions oil refinery (or PES for short) exploded in Grays Ferry on June 21, 2019, causing a massive fire and sending a bus-size piece of debris flying across the Schuylkill.

Investigations into the explosion found that it could have been much worse. If it hadn’t been for a single employee in PES’ central control room who performed what the industry calls a “rapid deinventory” shortly before the refinery’s computer system went offline, the explosion could have released more than 143,000 pounds of a highly toxic gas called hydrogen fluoride into the atmosphere, impacting over 1 million people, according to the company’s own risk management plan, and potentially killing thousands.

I was not in Philadelphia when the explosion occurred, but I remember it quite vividly, because only the day before, I had driven to western Pennsylvania to begin fieldwork for my research on what makes people consent to the presence of the coal and natural gas industries in their backyards.

The irony was not lost on me when only a day later, an oil refinery I had paid no attention to previously exploded less than three miles from my own backyard.

Hilco’s plans for the PES refinery

Today, PES has been shut down and the 1,300-acre complex sold for $225 million to the real estate development firm Hilco, which aims to turn the site into a distribution and commercial hub. A lot of the coverage of the planned development has been positive, with StateImpact highlighting Hilco’s promise of “good wage jobs” and sustainability and WHYY hailing the “first-of-its-kind public-private partnership” between Hilco and various government agencies “to connect thousands of Philadelphia public school graduates to (…) guaranteed opportunities for upward mobility.”

I have learned from researching fossil fuel-contaminated sites in western Pennsylvania that we should be skeptical of coverage like this. A maxim of former PES workers is that the site is so contaminated that it could only be used as an oil refinery. This may be partially self-serving logic (most of them would prefer to keep their jobs), but there is also more than a grain of truth in the idea that once a site has been contaminated by an environmentally destructive use, it is hard to convert it to anything else.

Take the example of the Muse property in Washington County, southwest of Pittsburgh: From 1923 to 1953, it was a coal mine before being converted to a toxic waste treatment plant and then a chemical recovery facility. In 2020, the Cecil Township’s board of supervisors proposed buying the land from ABB Ltd, an electrical equipment company for the princely sum of $10 to build a new public works building.

There is more than a grain of truth in the idea that once a site has been contaminated by an environmentally destructive use, it is hard to convert it to anything else.

But parents in the township are concerned that construction on the site would dig up harmful chemicals that would endanger children at the nearby elementary school. Given that the soil and groundwater on the site are contaminated by compounds that have been associated with excess incidences of diseases such as liver and kidney cancer and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, their concerns may be justified.

The same is true for the site where the South Philadelphia refinery has been active for more than 100 years: the soil and groundwater on the site are contaminated with more than a dozen chemical compounds, including benzene and lead above levels set by the state as acceptable for nonresidential property.

Digging foundations for new buildings has the potential to unleash vapors or contaminate groundwater, according to environmental engineering students at Drexel who studied the site. This is not to say that it cannot be remediated, only that we should be vigilant about how it is being done and by whom. And Hilco’s sunny forecast of a thriving commercial hub where a toxic wasteland once stood raises red flags.

Hilco raises red flags

A little bit of background research into the company shows that we might do well to be wary of them. Take for example Andrew Maykuth’s story in the Inquirer about Hilco’s track record: “Hilco is frequently called in to liquidate some of the nation’s best-known business failures,” he writes.

Maykuth gives the example of a small town in Ohio, where Hilco Global took over a General Motors stamping plant after the company went bankrupt in 2012 with the promise of attracting businesses to replace the lost jobs, but instead ended up selling the building’s materials for scrap and walking away after having created exactly zero jobs.

Communities living next to PES, who have also suffered their share of health consequences from the proximity of the refinery, have been mobilizing against it since at least 2015. Let’s make sure they don’t fight alone.

Perhaps more worrisome, in 2015 Hilco had to settle for $5 million with Maryland environmental regulators “over alleged violation of water pollution, erosion and sediment control, solid waste, hazardous waste, oil control, and asbestos laws,” during demolition of the Sparrows Point steel mill in Baltimore. (Hilco declined media requests for comment after both of these incidents.)

Just last summer, Hilco botched the demolition of the Crawford Coal Plant in Chicago (which they are redeveloping as a warehouse and distribution hub, similar to the plan here in Philly) which blanketed the low-income West side neighborhood of Little Village in a cloud of dust filled with mercury, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxide and other pollutants—in the middle of the pandemic. (This after a worker from that neighborhood died on the job site months earlier.)

Hilco issued an apology for “fear and anxiety” caused. The Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO), which helped shut down the coal plant and has opposed Hilco’s plans for redevelopment, said in a statement:

For almost two years now, LVEJO, the Little Village community, and those in solidarity have been sounding the alarm to decision-makers on the lack of commitment, transparency, and responsibility by Hilco for the consequences of their redevelopment activities and demolition plans on neighborhood residents and workers…

There must be immediate and comprehensive public disclosure of the mix of toxins and materials that made up the polluted dust cloud—the stack constituents—to enable affected residents to seek appropriate medical treatment and take any protective measures possible.

Trouble is brewing here, too. For example, one way Hilco plans to deal with ground contamination is to raise the surface elevation of any soil contaminated by the refinery above “base flood elevations.” But climate change could soon cause the Schuylkill to rise to higher levels. Also, the plan doesn’t address how the company will remediate underground benzene, a harmful chemical that has been linked to bone marrow damage and cancer. Hilco did not respond to my request for comment on their plan for PES.

Another red flag is that Evergreen Resources is collaborating with Hilco on the remediation process. Notwithstanding its quaint name, Evergreen Resources Group LLC is a subsidiary of Sunoco that was tasked with investigating and remediating soil and groundwater contamination while the refinery was still active and is behind questionable decisions like suspending city-mandated public meetings about pollution at the site for years and setting a site-specific standard for the amount of lead permitted in the soil that is more than twice the statewide health standard for non-residential sites.

So what recourse do we have?

Arguably, we should have a lot of say in policy decisions that affect our environment and our health, but the reality is very different: Anyone attempting to affect the permitting process around risky land developments faces an opaque and convoluted system that can be life-consuming and often yields very few concrete results.

A resident of Cecil Township just south of Pittsburgh told me that she and her friend went through years of doing research and attending public meetings before the board of supervisors integrated their feedback in the township’s new oil and gas ordinance. Even then, the new ordinance will only affect the construction of new well pads, not the one that’s already in their backyard.

There is also the silence and misinformation surrounding many risky land developments. Most of us are not even aware, for example, that there is a public comment period for risky energy developments, or how crucial it is to participate in it. In addition, energy and waste treatment companies often blatantly conceal the negative impact of their activities.

Tina Curry, from Yukon, PA, who has been fighting her neighboring waste treatment facility for the last four years, laments that residents planned to organize a kids’ fishing derby in a nearby stream, not knowing that it was contaminated with radioactive waste.

One of the consequences of all this dissimulation is that the people who are the most severely affected by the externalities of risky land developments end up also shouldering most of the cost of fighting against them. Tina has lost a brother and father-in-law who lived next to the facility. Her husband had to have his voice box removed, also because of cancer.

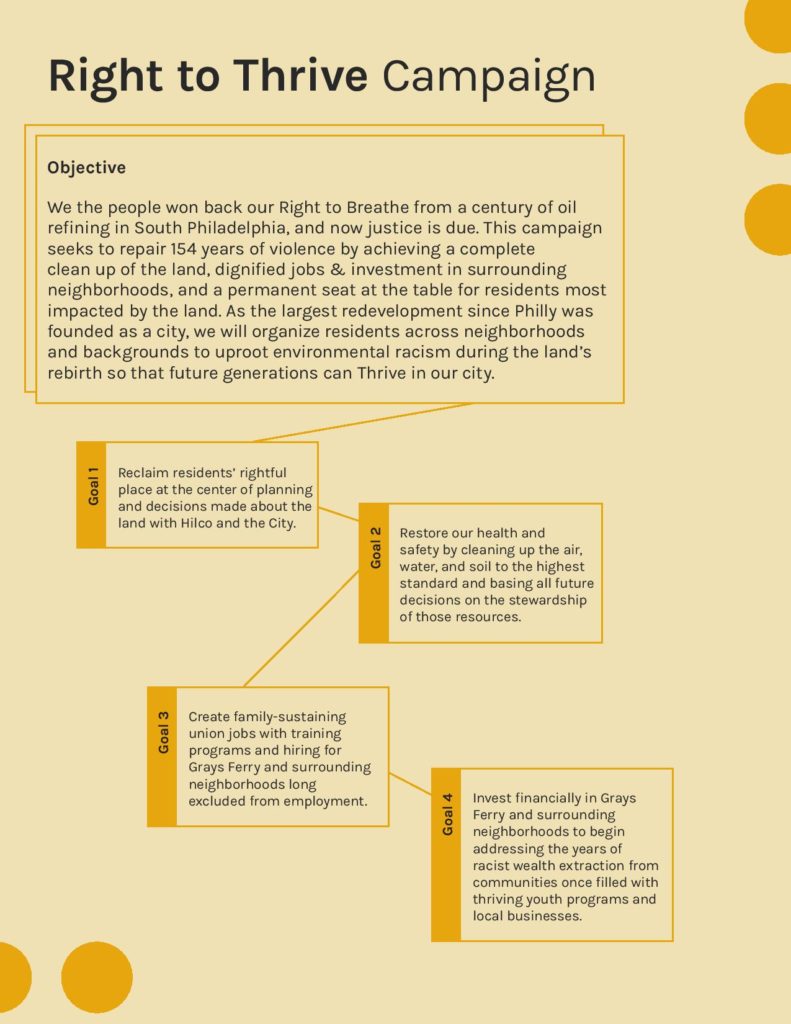

Communities living next to PES, who have also suffered their share of health consequences from the proximity of the refinery, have been mobilizing against it since at least 2015. Let’s make sure they don’t fight alone.

The good news is, there is already a movement to join. I don’t know about you, but I don’t want our kids to get their professional development training on ground that could be soaked in benzene and other toxic chemicals. Let’s not be the suckers who organize a kids’ fishing derby on a radioactive stream.

Click here if you want to get involved.

RELATED STORIES FROM THE CITIZEN

- In Chicago and D.C., residents and government came together to close polluting plants in their community. In Philly, City Hall won’t even take real action on the PES refinery site.

- A Drexel University class studied ways to mitigate what happens to Philly’s PES refinery site. Here, a student lays out proposals to benefit those who most need it: Philly residents

- Residents near the PES refinery have suffered from poor health for years. So why is everyone only talking about jobs?

Helene Langlamet is a PhD candidate at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. Her dissertation research focuses on the power of the coal and natural gas lobbies in western Pennsylvania to harness public opinion in order to achieve desired regulatory outcomes at the local and national level.

Header photo by Elvert Barnes / Flickr