In January, when teachers in Los Angeles went on strike, Tyler Okeke—the 17-year-old nonvoting member of the LA Unified School District school board—noticed something that disturbed him for months afterward: the teachers union, charter school supporters and others who fund elections got all of the attention. No one seemed interested in the needs of students.

So on Tuesday, Okeke proposed something that could change LA politics for generations to come: Lowering the voting age to 16 for school board elections. His fellow board members unanimously approved a resolution directing the superintendent to explore the possibility for 2020.

That puts Los Angeles in line with Berkeley, where 16-year-olds already elect school board members, and with other towns and even states around the county that are lowering the voting age to allow 16- and 17-year-olds to cast a ballot.

Just imagine if Philly had something like that.

Twenty-two percent of Philadelphia’s population is under 18, while over 32 percent of the resident’s living in high poverty are also under 18. Many are also Philadelphia public school students, nearly all of them eligible for school breakfast and lunch programs under constant threat from federal cutbacks, and often forced to languish in school buildings that are environmentally toxic, with no remediation in site.

Meanwhile, two-thirds of those under 18 can’t read at grade level, leading to a situation whereby a quarter of Philly adults are functionally illiterate. About 80 percent of 16- to 19-year-olds are unemployed, 11 percent are not in school and not working and 41 percent live in households that have unemployed parents. At one point, public interest law firm Phillips Black discovered Philadelphia, by itself, houses 9 percent of the nation’s juvenile prison-lifer population. And with the city homicide rate rising, 15- to 17-year-old Philly residents represented 20 percent of all shooting victims from 2015 to so far in 2019, about 8 percent of those in 2019 alone so far.

On top of all that, climate change will have Philly temperatures feeling like Memphis, Tennessee, by 2080, one among a long list of climate-driven concerns that’s absolutely mortifying “Generation Z” as well as the ongoing threat of mass school shootings, two issues that have under-18 teens pouring out of classrooms and into the streets.

With the city homicide rate rising, 15- to 17-year-old Philly residents represented 20 percent of all shooting victims from 2015 to so far in 2019, about 8 percent of those in 2019 alone so far.

And when they reach the end of the marching road they realize the best they can do is yell and scream because, at the moment, they can’t vote. Imagine how disheartening that can be at this pivotal moment in our city’s history, which is caught up in this very dangerous and uncertain national moment we’re all living through. All the more reason to lower the voting age to 16, before society loses that fierce mobilizing energy for change and another generation of young people become too jaded and depressed to do anything about the future that faces them.

We allow our 16- and 17-year-olds to do any number of very adult things: At a basic level, we let them own cell phones and spend inordinate amounts of time on screens watching everything from “Mature Audiences” video games to similarly rated Netflix shows. We allow them to drive cars—big, metal, unpredictable ton-heavy machines that kill humans on impact, even as teenagers are increasingly distracted at the wheel. Adults are even more accepting, begrudgingly, of the notion of teens engaging in sexual activity. We let them, for the most part, surf aimlessly into the darkest corners of an open Internet. These are just the things we, as adults, allow.

Articles by Charles D. Ellison about votingRead More

But we’re not really allowing them, beyond classroom projects and the occasional school walkout, to mobilize and vote on important issues. Bad enough most voting adults aren’t parents —only 30 percent of all 2018 midterm voters nationally identified as parents, and just 11 percent were parents of children under 18. Even as public education systems crumble and face crises of their own, K-12 education issues don’t even register as a priority topic in recent election cycles.

It’s one reason explaining why President Trump has yet to fire his embarrassing and not-so-liked education secretary Betsy DeVos—it’s not that she’s capable, it’s just that he’s noticed voters and policymakers don’t really care all that much about K-12 education issues. So, he figures, why should he? It’s the same in Philly: public schools are in a perpetual state of struggle and disrepair, but there’s no sense of immediacy around response to the problem.

But that could change if Philadelphia, as a major city, were to do what several smaller cities and towns have already done: allow 16- and 17-year-olds to vote. It would dramatically change the political conversation and calculus on key issues, such as education, because city leaders would have a new, massive and visibly pissed-off electorate to immediately answer to.

Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) from Boston, in her first term, sees the need. She’s pushing to have the voting age lowered to 16, citing how her state, Massachusetts and others already allow 16-year olds to register early so it’s automatic by the time they’re 18. “I propose an amendment that will lower the mandatory minimum voting age from 18-years-old to 16-years-old for federal elections, giving young people the power to elect members of Congress and the President of the United States,” said Pressley in a House floor statement. “In the Massachusetts 7th, young activists remind us daily what is at stake, and just how high those stakes are. Our young people are at the forefront of some of the most existential crises facing our communities and our society at large.”

Research shows that 16- and 17-year-olds are as informed and engaged in political issues as older voters.

In L.A., Okeke’s proposal would open up the franchise to nearly 61,000 eligible voters who would have a direct say in how their schools’ function and how they’re budgeted, too. Takoma Park, Hyattsville and Greenbelt, Maryland are three small suburban cities where 16- and 17-year-old residents can vote in municipal elections. Washington, D.C., is debating the same, too. Throughout the U.S., there are 15 states that allow 17-year old residents to vote in presidential, congressional and gubernatorial primaries. And places like Austria, Argentina, Brazil, Germany, and the United Kingdom let 16-year olds vote in local, regional and national elections.

Conversations about and organizing around the youth vote are usually excitable come election cycle time, but each make two large mistakes: 1) overestimating Millennial turnout that still continues to underperform; and 2) completely ignoring the potential power that’s eager to mobilize the way we need it to.

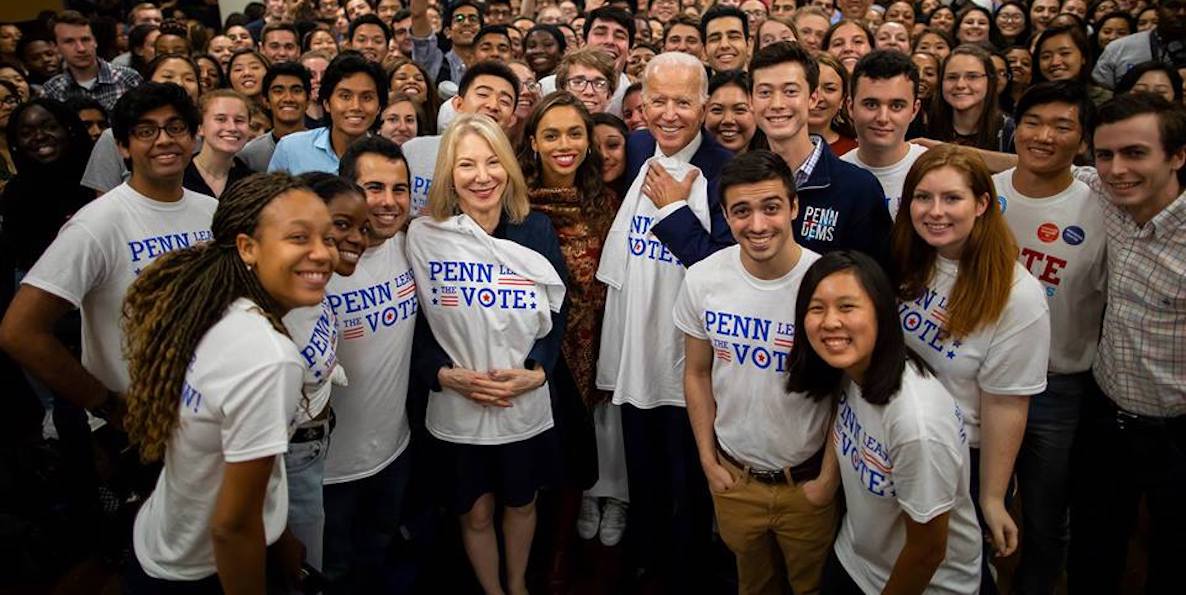

The 2018 midterm election saw Millennial turnout grow to 31 percent, 10 percentage points higher than it was in the 2014 midterm. (And, indeed, that increase was felt in Philly, especially in the University City district.) But, that’s still depressingly low: voters 18-29 were just 13 percent of the overall voting population nationally, when they are nearly a quarter of the U.S. population. They continue to electorally punch below their national weight, even after 67 percent of Millennials, in a pre-2018 election Washington Post/ABC News poll, claimed they were going to vote. Meanwhile, voters age 45-65 accounted for 39 percent of the electorate and those 65 plus accounted for 26 percent of the electorate.

Arguably, the biggest opportunity missed in this moment of student-led school protests is the failure of anyone to bring up how these young people could vote. Perhaps a more useful exercise is to help them start a nationwide movement to lower the minimum voting age to 16.

At what point do frustrations boil into either apathy or jaded detachment? What if Philadelphia City Hall remains in the hands of people who aren’t moved to immediate solutions to the homicide, poverty and education crises in the city?

While these teen movements on gun control, education and climate crisis might be inspiring to watch, adults do under-18 teens a great disservice by not allowing them to officially participate in the process. Beyond the protests, walkouts, and profanity-laden calls to Congressional offices, there’s not much under-18 students can do legitimately to swing the pendulum towards a comprehensive gun control or climate crisis response bill in Congress or in their state capitols or in their city halls. The conversation, indeed, is healthy and educational; and there is an opportunity for under-18 students to become involved as coordinators, organizers and volunteers — whether in the digital or physical space.

But, ultimately, there is a concern that if many of them are not turning 18 and thereby not eligible to vote by the time November 2020 rolls around, the issue and civic society as a whole may have lost a prime moment to ensure their political and public policy contributions. That’s a tragic outcome considering so much policy is made that directly impacts young people under the age of 18 — and without their input.

That’s not to say students should stop doing what they’re doing now. But, at what point do frustrations boil into either apathy or jaded detachment? And what happens if Republicans keep the White House and the Senate? What if Harrisburg stays in control of pro-gun conservatives who ignore mass shootings and climate crisis impacts? What if Philadelphia City Hall remains in the hands of people who aren’t moved to immediate solutions to the homicide, poverty and education crises in the city?

There’s evidence to suggest lowering the voting age increases turnout and also encourages long term civic participation. A 2006 study by the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement found through its interactive “KidsVoting USA” model that “KVUSA students were much more responsive to the civic environment, much more attuned to political messages flowing from media and schools, and more willing to share their knowledge and opinions with parents and friends. The sheer size of their discussion networks had grown significantly.”

About youth voting in PhillyRead Even More

Another benefit was that “kids Voting appears to provide an added boost for minority and low-income students.” A study of Austrian 16-year old voter habits found higher cases of turnout and better voting habits over time, as well . The National Youth Rights Association offers its Top 10 reasons for lowering the voting age, as does advocacy organization FairVote which explains that “[e]mpirical evidence suggests that the earlier in life a voter casts their first ballot, the more likely they are to develop voting as a habit. While one’s first reaction might be to question the ability of young voters to cast a meaningful vote, research shows that 16- and 17-year-olds are as informed and engaged in political issues as older voters.” Even The Economist argues: “catch them early.”

Making a change like this in Philly would not be easy. It would likely require a change to the state election code, allowing the city to create its own age parameters for voting—something the Republican-led legislature is unlikely to push through for heavily-Democratic Philadelphia. But there is national precedent for lowering the voting age: Just 47 years ago, through ratification of the 26th Amendment in 1971, 18-year-olds gained the right to vote, as a direct consequence of the Vietnam War draft. The logic went, if they’re old enough to fight, they’re old enough to vote.

The same could be said for the time we live in now: If it’s okay to drive a car, to attend schools that are falling down, to face the prospect of shootings in those schools, and to have a voice in the national conversation at the age of 16, then it should also be okay to have the right to vote.

Charles D. Ellison is Executive Producer and Host of “Reality Check,” which airs Monday-Thursday, 4-7 p.m. on WURD Radio (96.1FM/900AM). Check out The Citizen’s weekly segment on his show every Tuesday at 6 p.m. Ellison is also Principal of B|E Strategy, catch him if you can @ellisonreport on Twitter.

Header: Phil Roeder via Flickr