In March, as the coronavirus hit Philadelphia, photojournalist Raymond Holman, Jr., realized it presented a unique opportunity to tell (and show) the human stories unfolding in our city in the grips of a global pandemic. In particular, he wanted to witness the effects of Covid-19 on Black Philadelphians—who, we’d later learn, have been disproportionately affected by the disease. By the beginning of April, Holman decided to make an intervention, noting that access to healthcare was a critical issue for the African American community in Philadelphia.

What he found on his trips to North Philadelphia was an atmosphere of fear and uncertainty that was both palpable and photographable. He also found heroism, in the doctors and nurses, led by Ala Stanford, of the Black Doctors Covid-19 Consortium.

![]() Every week for the first two months of the pandemic’s first wave, the Consortium offered free testing to residents in Black neighborhoods, sometimes setting up in the parking lots of Black churches. To date, the BDCC has administered over 10,000 tests—conducting as many as 350 tests per day in some weeks this past spring. More recently, the consortium has positioned itself within the city’s pandemic budget, raising funds on its own and established a trusted healthcare interface with the Black community in Philadelphia.

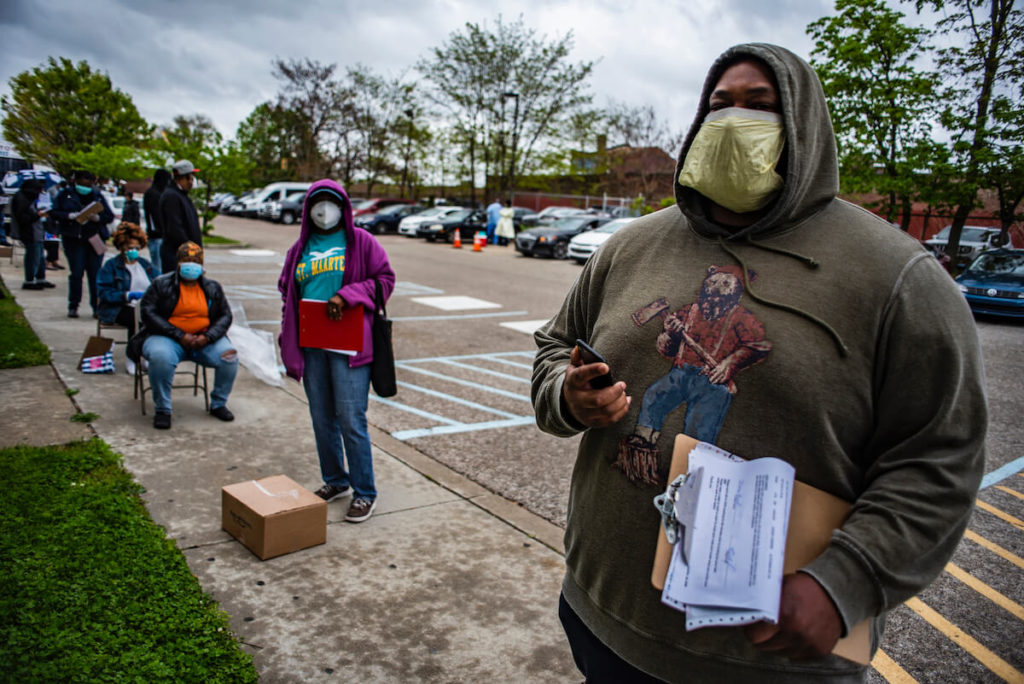

Every week for the first two months of the pandemic’s first wave, the Consortium offered free testing to residents in Black neighborhoods, sometimes setting up in the parking lots of Black churches. To date, the BDCC has administered over 10,000 tests—conducting as many as 350 tests per day in some weeks this past spring. More recently, the consortium has positioned itself within the city’s pandemic budget, raising funds on its own and established a trusted healthcare interface with the Black community in Philadelphia.

“I decided to go and see what was going on with a need to also capture images,” Holman says. Taking pictures “is something I really need to do. It’s burning in my heart all the time. All the time.”

A banker-turned-photojournalist in 1989, Holman has shot photos for The Inquirer and Daily News. His photography, focusing on family caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia was exhibited in the African American Museum of Philadelphia in 2008. His photos also appeared in “Committed to the Image,” the first exhibit of Black photographers from around the country at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and in a publication called Black Photographers from 1864 to Present.

Holman’s approach to photography is evangelical. He defines it as a deep-seated need to tell stories in a visual art form that provides a unique entry point into the human experience. The conditions of Covid-19 forced Holman to initially shoot his subjects from a distance, but as he learned more and as the BDCC continued to lead with bravery and safety, Holman settled in to his more traditional intimate focal points.

![]() For Holman, the unknown health risks and our general ignorance of the pandemic earlier this year did not deter his desire to capture the stories of our community coming together to manage the coronavirus. Holman’s (photographic) intervention captures images of fear, anticipation, compassion and anxiety. Together his work celebrates the frontline workers at the critical point of contact with a community struggling to confront the impact of one of the deadliest viruses in this nation’s history.

For Holman, the unknown health risks and our general ignorance of the pandemic earlier this year did not deter his desire to capture the stories of our community coming together to manage the coronavirus. Holman’s (photographic) intervention captures images of fear, anticipation, compassion and anxiety. Together his work celebrates the frontline workers at the critical point of contact with a community struggling to confront the impact of one of the deadliest viruses in this nation’s history.

Here, Holman talks about this extraordinary moment in Philly—and his photos that capture the complexities of surviving the coronavirus in the city of brotherly love.

James Peterson: Can you give us a sense of what made you decide to shoot the coronavirus/COVID-19 photos? What drove you to say, “Hey, I need to capture what’s going on right now with this pandemic”?

Raymond Holman, Jr.: In mid-March I started hearing about this Covid-19 situation, and it was starting to affect assignments and things I was going to do this year. And then I heard about an organization of Black doctors and nurses who were going to be giving free Covid-19 testing at a church in North Philadelphia. This was the beginning of April.

I decided to go and see what was going on with the need to also capture images. Because my relationship with photography is, it’s like a monkey on my back. I need to take pictures. And I don’t mean I need to just take pictures. I need to take pictures that are captivating and that soothe my soul.

So, I went to North Philadelphia just to see what the situation was like and just kind of figure out if it was safe being there. I knew hardly anything about Covid-19, and how to approach capturing some images. My first day was really kind of a trial step for me. How could I capture some images that were the style of images I wanted to capture and tell a story at the same time? So, I had an opportunity to speak to a couple of people there who were the creators of this particular consortium.

JP: Yes. That’s Dr. Ala Stanford’s group, the Black Doctors Covid-19 Consortium.

RH: Right, yeah. I stayed pretty far away, because my tendency when I capture images, I’m pretty close to people normally. But because I didn’t understand Covid-19, I didn’t know how it traveled from person to person, for the most part I shot with a long lens, a telephoto lens.

And from there, once I got the feeling that I should be capturing this group of people, every time I heard that they were going to a different location I went as a person with the intention of documenting what they were doing, because I thought it was really important that it be documented from the viewpoint of a Black person.

I did it for about four months. It just recently ended maybe a month ago now. But I would go on average three times a week. I would go out wherever they were and I would capture images. I remember—I think the third time I went out I went to a church up in Mt. Airy, Enon Baptist Church. And that particular day they tested 250 people, from what I understand. So, I have a lot of images.

JP: There’s an array of extraordinarily vibrant mask photos. And then there are images of caregivers. You capture some of the caregivers moving in and out of the space. Can you talk a little about those categories? You were obviously trying to get the more quotidian images of healthcare workers moving in and out of the space. Is that a fair way to describe those categories?

RH: Yes, it is. For example, there’s one image I captured where there’s an individual who is leaning backwards prepared to have the swab put in his nostril. Instead of waiting for the swab to actually go into his nostril I decided to capture it at a very far distance from his nostril. So, you only see a really small portion of the swab. And that’s actually one of my favorite images. It was creating an image and a feeling of anticipation of the unknown, because Covid-19 is unknown.

The people who were being tested for Covid-19, especially at the beginning when it first started —they had never been tested before, so they had no idea what it was going to feel like to put that swab in your nose.

JP: There are also, all of these striking images of people in masks.

RH: Right. I was at a mosque in Mt. Airy. I saw a guy 100 percent in protection garb from head to toe. I mean, he’s wearing this green protective gear. And he’s wearing this big mask.

At the time I saw him I said, “Jesus. Jesus Christ. This dude is stone cold protecting himself.” And I wanted to capture that image. So, when I put it into Photoshop, I made sure that I added intensity to the colors and contrast, and I did some other things, because I wanted people to be able to see his eyes also. And I wanted to feel as if maybe he was on planet Mars.

JP: He looks like an alien, almost.

RH: Yeah.

JP: Did you have a chance to speak with Dr. Stanford or any of the other healthcare workers while you were doing your work there?

RH: Oh, yeah. I actually developed a really good relationship with some of the people. Matter of fact, I was coming in so frequently that they got accustomed to me being there capturing images that some of the times I didn’t show up—when I didn’t show up, the next time I did show up they’d say: “Where were you?”

JP: Let’s go back to the beginning. How did you become a photographer?

RH: It was a hobby that turned into a career. I actually have a degree in economics, so when I came out of school, I was in banking for ten years. It took me an extraordinarily long time to turn a hobby into a career —about 15 years. It was very hard.

![]() I was the first person in my family to graduate from college. I majored in economics at Lincoln University. I had envisioned myself being in corporate America my entire career. Then I picked up a camera one Christmas holiday and was taking pictures around the Christmas tree. Eventually that step into photography became some sort of inner recognition that I could do photography. So, I started purchasing photography magazines and going to some exhibits. I’m basically a self-taught photographer. There were really no role models in the city that I could approach that were willing to share information on how to turn this hobby into a career.

I was the first person in my family to graduate from college. I majored in economics at Lincoln University. I had envisioned myself being in corporate America my entire career. Then I picked up a camera one Christmas holiday and was taking pictures around the Christmas tree. Eventually that step into photography became some sort of inner recognition that I could do photography. So, I started purchasing photography magazines and going to some exhibits. I’m basically a self-taught photographer. There were really no role models in the city that I could approach that were willing to share information on how to turn this hobby into a career.

So, it was very difficult. And I think one reason why I continue to do it is because I recognize how valuable photography is. I recognize the fact that I’m supposed to do photography. I want to have the opportunity to expose photography to young people of color who want to turn it into a career, especially here in Philly because Philadelphia is not friendly to the arts, especially photography particularly. It’s a beautiful path.

JP: It is.

RH: It’s a beautiful path. It’s a beautiful path. It can change society. It can change society, man.

JP: So, can you talk us through some of the logistics of the work? Did you wear a mask?

RH:I always wore a mask. We were always outside. I always wore a mask. And I noticed maybe two months ago, two and a half months ago the doctors and nurses started doubling up on masks. When I noticed that they were wearing double masks I started wearing double masks.

JP: Smart move.

RH: I understood by that point that being outside, because of fresh air there’s less likelihood of catching Covid-19. By that point I was shooting with a wide-angle lens and shooting with a medium lens–85 millimeter lens. So, I was getting pretty close to some extent, but I was always wanting to tell a story. I would shoot tight, I would shoot wide, and I would shoot at that intermediate length to make sure I was telling the entire story.

For the next stage of this project, I want to start focusing on people who have actually developed Covid-19 and have been able to move through it, move through the process. But what I’m realizing is some people are afraid to let others know they developed Covid-19. They are really afraid.

JP: That’s right.

RH: There’s a big story out here about that. And it’s not being told in the Black community. It’s probably not being told a whole lot in general in the world. But definitely not in the Black community.

Text by James Peterson; photos by Raymond Holman, Jr.

A man waits to be tested for Covid-19 at Triumph Baptist Church on W. hunting Park Avenue.