There’s already been a lot of attention on Mayor Jim Kenney’s last-minute pocket veto of the Drexel food-truck ban, where by declining to sign the bill, it expired at the end of Council’s term instead of passing into law.

The food truck ban was one of six bills that Mayor Kenney pocket-vetoed at the end of the term, and the Planning Commission also cancelled a few as we noted in our end-of-term wrap-up:

Here's the quick version of this storyShort on Time?

Planning also spiked a bill from Society Hill that would have made numerous changes including reducing development rights in the area near the Ritz Five theater and Positano Coast (presumably in response to the by-right approval of 300 apartments at the Sheraton hotel) and exempting the neighborhood from the new historic preservation incentives, which include relief from parking requirements, allowance of Accessory Dwelling Units, and easier residential conversion of industrial and institutional properties. Department of Planning and Development head Anne Fadullon reportedly panned the bill as “exclusionary” according to sources who attended. This too can come back next term, if Councilmember Mark Squilla will introduce it again over Planning’s objections.

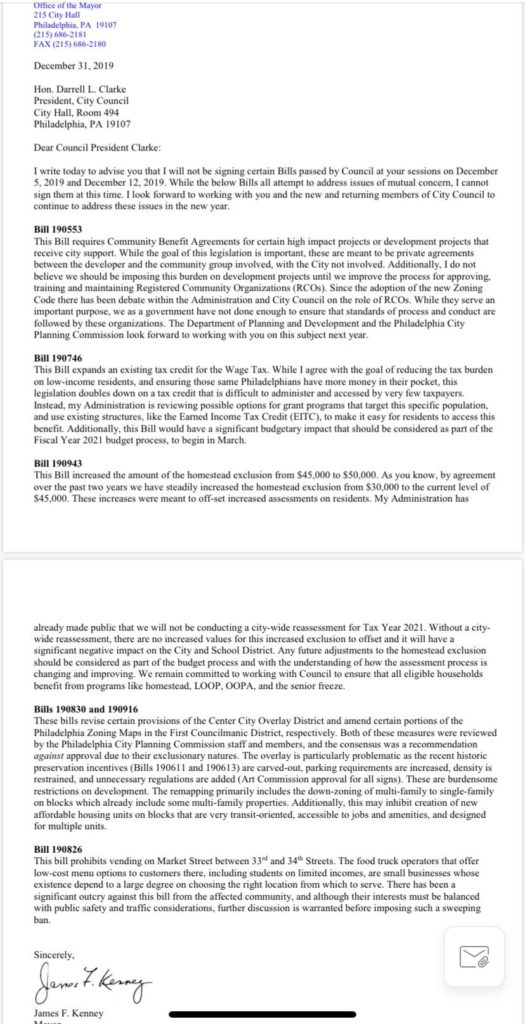

The administration released a memo explaining their pocket vetoes which is worth a read because of how it highlights the positive influence of the Planning Commission in a rare instance where they had some power over the process, and why it would be a good idea for them to have even more power during the regular course of business, relative to City Council.

The key sections here concern the vetoes of bills 190553, 190830 and 190916.

The first section about the Community Benefit Agreements bill (190553) recognizes some of the big problems with the Registered Community Organization (RCO) process that City Council typically doesn’t think very critically about. Community Benefit Agreements can be good, depending on the details, but they can also just be a way for local property owners to shake down projects—even public projects!—for unrelated amenities that have little to do with the project’s impact.

The Council bill, introduced by Darrell Clarke, just assumes that all RCOs would operate with a certain level of integrity, but as the mayor’s comments hint at ever-so-tactfully, there are almost no quality controls that the City imposes on these organizations as a condition for approval.

Be part of the planDo Something

So it’s great to see the Kenney administration, and the Planning Commission who approves the RCOs, gesturing in the direction of further rounds of RCO reform in the new term to create more public accountability there. For context, some other cities are actually dismantling these kinds of neighborhood power structures as an official part of the planning and zoning process, recognizing that they tend to amplify the opinions of a very unrepresentative and relatively privileged segment of the population. This is one area where we could really use a stronger Planning Commission with a freer hand to rebalance the City’s public outreach process with an eye toward gathering more representative opinions.

The other section of interest is the Society Hill rezoning veto, where Mayor Kenney, informed by Planning’s position opposing the bills, objects to the exclusionary nature of that legislation in a neighborhood that always seems to get whatever special treatment they ask for:

[R]ecent historic preservation incentives… are carved-out, parking requirements are increased, density is restrained, and unnecessary regulations are added. These are burdensome restrictions on development. The remapping primarily includes the down-zoning of multi-family to single-family on blocks which already include some multi-family properties. Additionally, this may inhibit the creation of affordable housing units on blocks that are very transit-oriented, accessible to jobs and amenities, and designed for multiple units.

It’s a reminder that these kinds of arguments for special snowflake status are only really going to carry weight with a District councilmember. From the perspective of somebody like the mayor or an at-large councilmember who gets elected citywide, they’re much less compelling, and more often objectionable.

From the mayor’s perspective, more housing construction in wealthier areas of the city means more jobs and tax revenue and more people who can live close to downtown jobs, which is right in line with their high-level planning, affordability and environmental priorities.

Unfortunately, the mayor and the Planning Commission only had this kind of power this time because they were reviewing the bills at the end of the Council term, which only happens once every four years. But this is only the case because of an unfortunate detail of the City Charter, where Planning Commission opinions are advisory-only, even though other Commission decisions—like the Art Commission, for example—are actually the final say on matters.

It would be an enormous improvement to local politics if the Charter were changed to make the Planning Commission’s decisions binding too, so that they would always have veto power over rezoning bills, code changes and city plan amendments, and would be constantly looming over land-use debates as a hard backstop to any bad ideas coming out of Council.

As interest has been building around a City Charter rewrite, changing Planning Commission recommendations from advisory to binding would be a critical move for weakening councilmanic prerogative and holding the City accountable to important big-picture policy goals for climate change, affordable housing, and more.

In the meantime, one of our New Year resolutions for 2020 is to see more of this kind of rhetorical verve from Planning and the mayor on housing and planning issues, and more assertive policy entrepreneurship that doesn’t just relinquish the whole policy agenda and the public narrative around planning to City Council.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

Want more? Check out these related articles:

- Philadelphia is richer than it was in 2016. So where’s all that money going?

- The mayor’s zoning board is making bad decisions counter to the his own plans for the city

- The opposite of councilmanic prerogative is not rocket science—it’s planning