Paul Levy, president and CEO of the Center City District, has long been our chief evangelist for economic growth.

He has maintained that cities cannot grow just by taxing and spending. They have to figure out ways to grow that tax base, by attracting new residents and businesses.

Yes, he concedes, Philly has been adding jobs, albeit our median household income lags far behind peer cities. But, with city tax revenues now rising, what have we been doing with that money? Have we been smartly investing in growth?

Sadly, that has not been the M.O. of Philadelphia (or many other Rust Belt cities) for some time. Levy’s new report, Investing the Proceeds of Growth: City of Philadelphia Budget Choices 2020-2024, represents as deep a dive as I’ve seen into what our local government’s priorities have been for the last 20 years.

It follows a recent report from City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart that delves into the historic levels of spending by the Kenney administration. When I caught up with Levy this week, that’s where our conversation began.

Larry Platt: It’s budget season, and the mayor has proposed a record $5.2 billion budget, a 29-percent increase over four years. Controller Rhynhart recently came out with a report that looked at all that spending. How does your report differ from that one?

Paul Levy: Rebecca looked at increased spending. We asked, ‘What is the increased spending focusing on?’ And we didn’t just look at the Kenney administration. We actually looked back over the past 20 years.

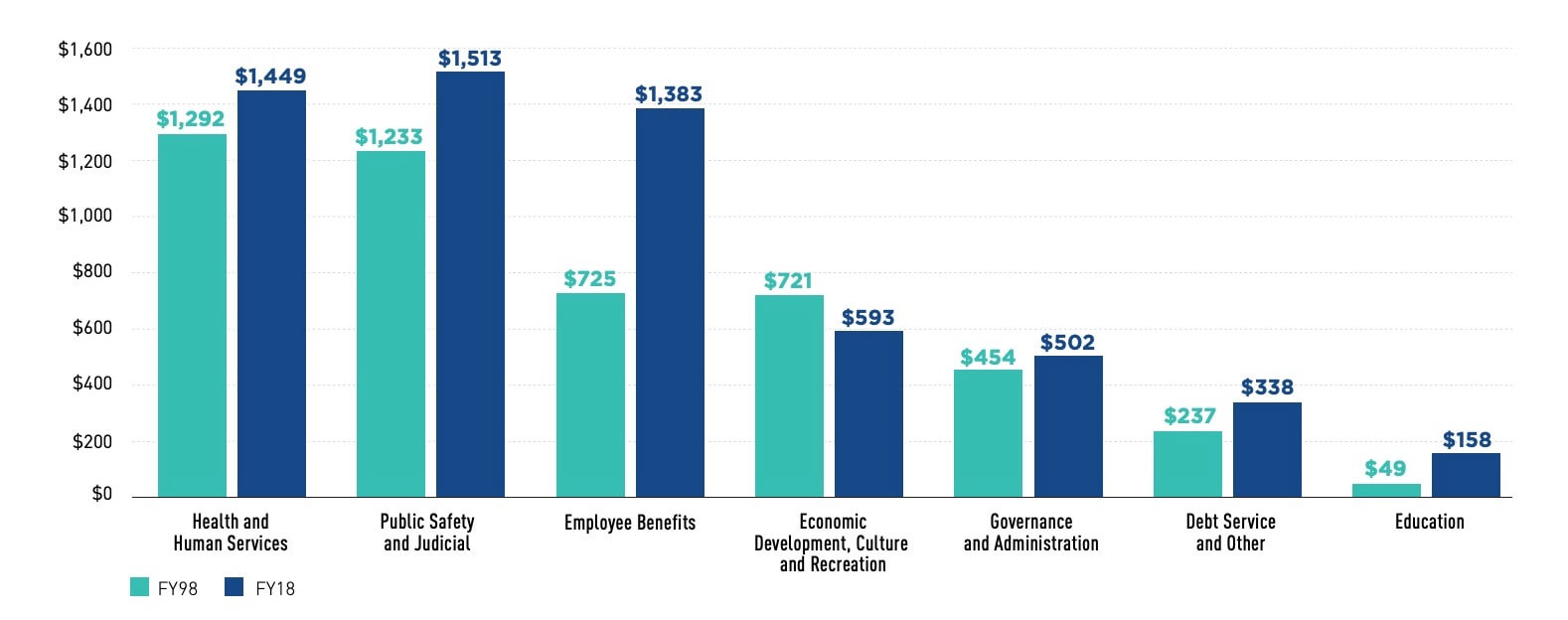

LP: And you broke that spending up into three distinct strategies, and the breakdown of that is very stark. What you call Strategy 1 makes up—shockingly—50 percent of all city spending.

PL: That’s right, 50 percent of the budget goes to address crime, criminal justice Call Mayor KenneyDo Something

LP: And what you call Strategy 2 is the spending that you and I have been calling for—investing in growth—and this is the first time I’ve seen it laid out so starkly just how much we’ve disinvested in that category over the years.

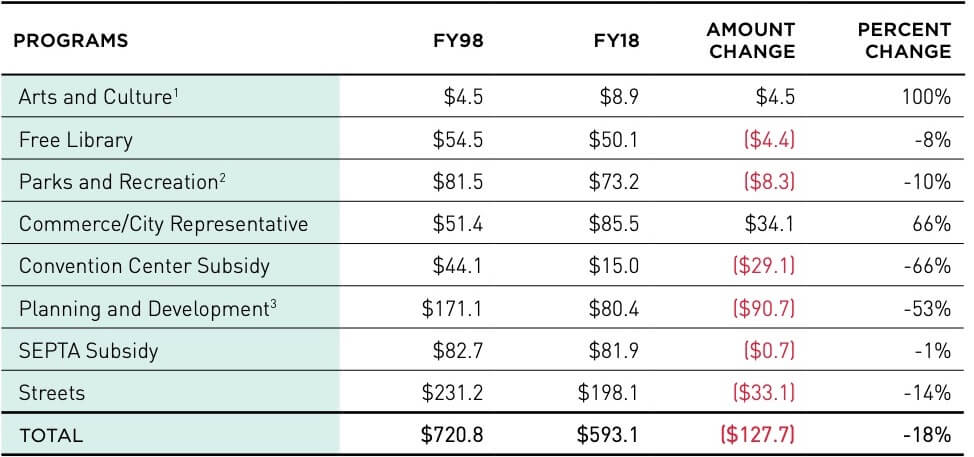

PL: Yes, these are investments in quality-of-life issues. Cleaning streets, parks and recreation, arts and culture, sanitation, education, infrastructure, economic development. These are investments in attracting and retaining more residents and businesses to the city so we can grow the tax base. And that makes up 13 percent of the budget.

LP: I was stunned at how low that is. In fact, you provide charts that show we’re spending less today on this than 20 years ago. (See figures below.) It’s proof of chronic disinvestment over two decades.

PL: Yes, we started looking at 1998. So it’s important to keep in mind that we’re not talking just about the Kenney administration. We’re looking at long-term trends. Remember, Strategy 2 spending represents the things that people are complaining about, things like potholes and sanitation. Well, spending on Streets is down 14 percent over 20 years, and that’s adjusted for inflation. Planning and Development? Down 53 percent.

LP: Which suggests that those complaints are born of specific policy choices. What’s clear is that we’re heavily invested in the social safety net—your Strategy 1—but underinvested in ways to grow the economic pie, right?

PL: That’s right. We have real challenges and we need to address them by spending, but there’s no comparable investment in growing family-sustaining jobs and creating the conditions to attract and retain residents and businesses.

LP: One way to grow is to reform our tax system so the city can compete with neighboring states and the suburbs, which gets us to tax reform, your Strategy 3. Here’s the quick versionShort On Time?

In the past, you’ve called for addressing that by lobbying to change the state’s uniformity clause which would open the door to taxing commercial properties at a different rate than workers. But now you’ve come up with something else: A call for a five-year commitment to a 0.5 or a 1 percent reduction in those taxes.

PL: It was really interesting to go back and start in the ’90s and look at what was done. Rendell was all about Strategies 2 and 3. From 1996 to 2010, the revenue foregone due to tax cuts was never more than 1 percent of the budget in any year. Today that number is 0.16 percent. If we just go back to 1-percent wage and BIRT tax cuts, that’s a $50 million investment in growth. The predictability that would come with a five-year commitment to this effort could make a big difference.

LP: I don’t see much of this thinking in the mayor’s new budget proposal. Have The Center City District ReportRead More

PL: We shared this with the mayor and walked him through this. It was a good meeting.

Photo by Scott Serhat Duygun on Unsplash