![]() I am a white, Jewish woman.

I am a white, Jewish woman.

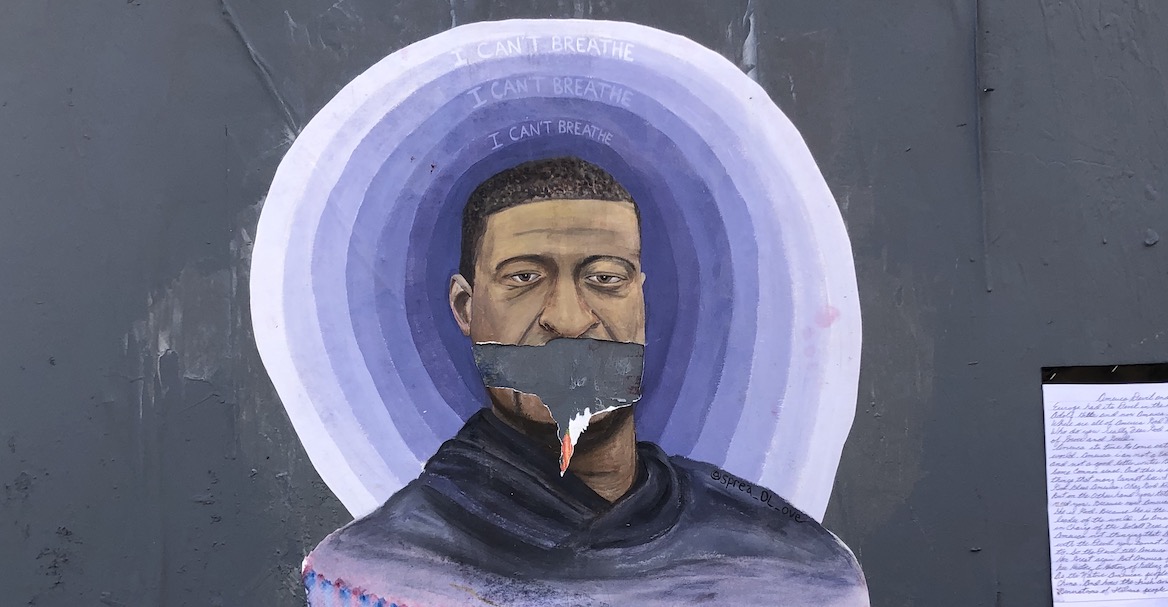

This means I never had someone call the police on me for asking them to leash their dog in a public park, as happened to Christian Cooper in Central Park. I have never feared being gunned down by three white men, while simply jogging in my neighborhood, as Ahmaud Arbery was in Brunswick, Georgia. And, I never have worried whether a cop, while unjustly arresting me, will cut off my airway, as happened to George Floyd in Minneapolis.

I am a white, Jewish woman and my daily privilege comes simply because I am.

As a professor at Temple University, I once believed if I just learned more about the history of race in our nation, I could identify with many of my black students. I desperately wanted to be able to feel what they experience. I wanted to be a better professor. Yet, now I know, I can never truly feel the discrimination they face every day, simply by living—but I can recognize it!

As with many social issues, in the case of Covid-19, placing this responsibility on those who are the victims, allows the rest of us not to have to discuss the deeper divides in our society.

Much of what I have been reading about race in our nation concerns the legacy of slavery. The materials connect the past to our current issues of inequality and racial discrimination.

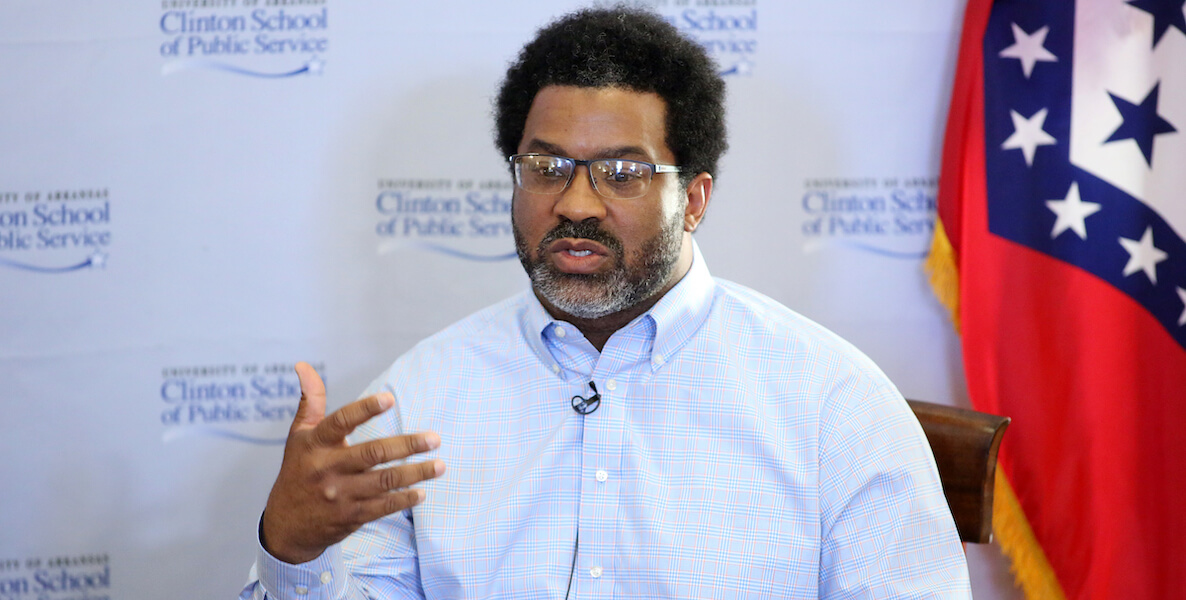

![]() For example, Dr. Sabrina Strings, an associate professor of sociology at the University of California at Irvine, recently wrote in The New York Times about the connection between slavery and health conditions in the black community. As she reports, “available analyses show that on average, the rate of black fatalities is 2.4 times that of whites with Covid-19.”

For example, Dr. Sabrina Strings, an associate professor of sociology at the University of California at Irvine, recently wrote in The New York Times about the connection between slavery and health conditions in the black community. As she reports, “available analyses show that on average, the rate of black fatalities is 2.4 times that of whites with Covid-19.”

Data from the City of Philadelphia, as of May 13, showed that African Americans accounted for at least 46.9 percent of Philadelphia’s almost 19,000 coronavirus cases.

Dr. Strings argues that while the media has latched onto the narrative about the relationship between obesity in the black community and their high rates of Covid-19, there is little scientific evidence to support this. Instead, this storyline serves to “reinforce an image of black people as wholly swept up in sensuous pleasures like eating and drinking…”

Simply put, larger society wants there to be blame placed at the feet of the victims of what Strings calls the failures of “our social structures,” such as housing and employment.

As with many social issues, in the case of Covid-19, placing this responsibility on those who are the victims, allows the rest of us not to have to discuss the deeper divides in our society.

We do not have to take responsibility for, as the AMA reports, racial minorities experiencing systemically lower quality health care. We can ignore that minority communities have less access to healthy foods and green space, while as the same time have excess exposure to environmental hazards. We can move on in our lives, not recognizing, as Dr. Camara Phyllis Jones, a Senior Fellow at the Morehouse School of Medicine has reported, racism, “continues to have profound impacts on opportunities and exposures, resources and risks.”

I once believed if I just learned more about the history of race in our nation, I could identify with many of my black students. Now I know, I can never truly feel the discrimination they face every day, simply by living—but I can recognize it!

Most importantly, agreeing with Strings and Jones about continuing societal inequality would mean embracing an uncomfortable truth—we are not as enlightened a society as we believe we are. For example, we would have to admit that the death of Ahmaud Arbery was nothing different than the approximately 4,000 lynchings that occurred in a dozen Southern states between 1877 and 1950. But we do not like these truths, they interrupt our comfortable lives.

![]() I am a white, Jewish woman. I live a life of privilege, merely because I am.

I am a white, Jewish woman. I live a life of privilege, merely because I am.

I know no one will mistake me for the valet. I do not worry that I will not get good care at the doctor’s office because of my race. I can live my life never having to fear that reaching for the glove compartment, when stopped for speeding, might get me killed—but others in our society do carry these fears and concerns every day. Yes, recognizing this makes us uncomfortable. It should make us uncomfortable—even more, it should make us want to act.

Dr. Abby Jones is an Adjunct Professor at Temple University in The Communication and Social Influence Program in The Klein School of Communication. Having worked professionally in the political and strategic communication arenas, she is also the owner of AJ Research, a computer-aided content analysis firm.