With a few fleeting exceptions, Philadelphia City Council has been, for decades, a place where vision goes to die. It was once called the “worst legislative body in the free world” by a former mayor, and it has long been characterized either by members looking out for their—or their benefactors’—private interests above the common good, or by an almost comical emphasis on constituent service, at the expense of actually legislating.

Granted, this current Council, while still clinging to its past excesses, has seemed to legislate more than past ones, even if said legislation is stunningly simple-minded—barring cashless retail outlets rather than growing jobs?—and kicks the hard issues down the road. (Seriously, not one hearing on our pension crisis?)

But help may be on the way. This election cycle, change is in the air amidst an electorate that’s freaking out over national politics, and there are indications that a new class of Council candidates are planning to actually inject some vision into the mix; between now and election day, we’ll introduce you to some, and zero in on their ideas.

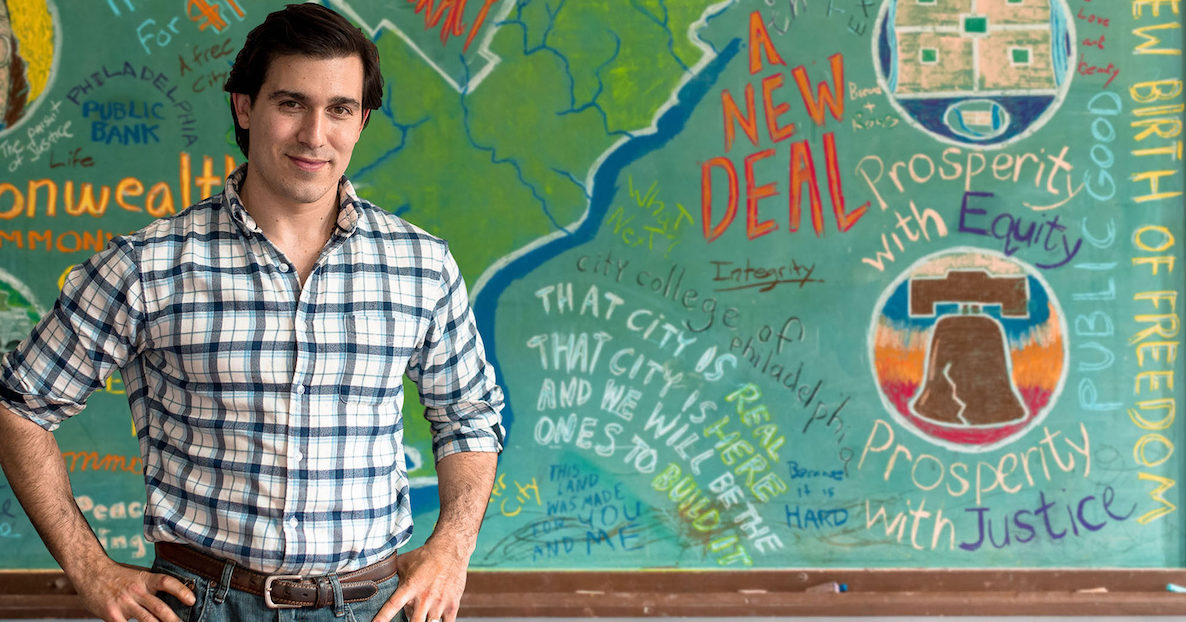

DiBerardinis is full of ideas. But his biggest, and perhaps most fantastical, idea is what he calls A New Deal for Philly. Literally: A grassroots public works project.

Thirty-seven-year-old Justin DiBerardinis, running for Council-at-large, is one such potential change agent. If the name sounds familiar, it’s because he’s the son of the city’s former Managing Director Mike DiBerardinis—Mike D—a widely respected practitioner of government. But the son is more thinker than technocrat; DiBerardinis, whose recent fundraising report placed him in the top five of all candidates with $140,000 cash on hand and who has garnered a slew of endorsements, including one from Ed Rendell, says it’s time Philly gets out of the small ball game. Mario Cuomo used to say, “you campaign in poetry but you govern in prose,” and DiBerardinis is all poetry, his rhetoric seeking to summon Philly to its better angels.

![]()

When I caught up with him last week, he launched into his elevator pitch, which isn’t a laundry list of programs or critiques of current policies so much as a kind of civic pep talk. “For generations, the city was sure it was dying and we had a politics of decline,” he said. “We were parochial, having to do with less each year, each interest group trying to hold onto its share. Well, we’re not dying. Now the question is what will be the terms of our prosperity going forward? This is the most exciting moment in Philadelphia in my lifetime, because we have the chance to adopt a generationally-forward looking platform and take on big challenges together.”

And what follows, in strings of run-on sentences, is more of the same, a mix of idealism with street smarts. DiBerardinis is full of ideas, everything from making the wage tax progressive—giving a break, in other words, to those who need a hand up—to using property tax incentives to “build a green city one row house at a time.” But his biggest, and perhaps most fantastical, idea is what he calls A New Deal for Philly. Literally: A grassroots public works project.

“When our country had a poverty rate as high as Philadelphia’s, this is what we did,” he explains. “We put people to work. I’m talking about hiring teacher’s aides in every K-5 classroom, street sweepers for our streets and parks, traffic enforcement officers to keep our kids safe.”

“We should be measuring ourselves not by our private wealth, but by our shared wealth,” DiBerardinis says. “Our parks, our libraries, our schools, our buses, our trains. These are the public assets we should be investing in.”

Before you conclude that DiBerardinis is just a throwback big city tax and spend liberal, he complicates matters a bit by talking about his bold plans not as social safety net but as part of a pro-growth strategy in left-behind neighborhoods. He knows those neighborhoods, having grown up in Fishtown before the dog grooming storefronts. His was, and remains, a family devoted to public service; his three siblings are all school teachers. They were all, he reports, taught to go beyond complaint. Once, at 17, DiBerardinis remembers a policy-oriented disagreement with his dad. “‘Okay, you’re right,’ my dad said,” DiBerardinis remembers today. “And then he said: ’Now what are you going to do about it?’”

Young Justin grew up amid the lore, and lure, of public service and social justice. His father once led a squatter’s rights campaign in Kensington. His mother, Joan Reilly, had been part of the Camden 28, a group of radical Catholics who raided the Camden draft offices during the Vietnam War in order to destroy its records.

So it was no surprise about a decade ago when, as a community organizer himself, Justin helped a neighborhood put aside its internecine battles and rebuild the overcrowded and dilapidated Willard Elementary school in Kensington, a lesson in grassroots power that informs his politics today. “If you want better outcomes from government, you’d better find or build new power sources to get it,” he says. “One thousand neighbors united with collective vision and collective will? That’s how you put pressure on elected leaders.”

Nor was it a surprise when DiBerardinis served six years as legislative aide to Councilwoman Maria Quiñones-Sánchez. Quiñones-Sánchez is one of the more interesting political figures in our midst, a gritty survivor who, time and again, takes on her own party establishment and emerges victorious. She bucks the system and has the scars to show for it. But on election day, her nonconformity has always been rewarded.

“From Maria, I learned not to be afraid to challenge orthodoxy,” DiBerardinis says. “She wasn’t afraid to find common ground with uncommon partners, working with [then-Councilman] Bill Green and [current Councilman] Curtis Jones on tax reform and other issues. You wouldn’t expect her to be such close partners with those who she was so different from—different parts of the city, different socio-economic backgrounds—but she put the common interest first.”

Yes, DiBerardinis might be floating some pie in the sky ideas, and here’s hoping he thinks more deeply about how to fund them. But better a cacophony of ideas than the same-old transactional politics that has gotten us where we are, right? Better vision than cynicism, no?

It’s striking how often DiBerardinis speaks of common things. In these bifurcated times, it seems ingrained in him to think about the whole of the city. That’s a lesson learned during his most recent gig, as the Director of Programs and Partnerships at Bartram’s Garden, from which he’s taken a leave of absence to campaign. With its 45 acres of public, nationally historic land in Southwest Philadelphia, Bartram’s Garden has become a public park and racially diverse meeting place for different Philadelphias and Philadelphians. It’s led him to think deeply about how we define what’s public.

“We should be measuring ourselves not by our private wealth, but by our shared wealth,” he says. “Our parks, our libraries, our schools, our buses, our trains. These are the public assets we should be investing in.”

Ah, yes, investing. Therein lies the rub. He wants to do a whole helluva lot of it. When I ask him how a city with a still-shrinking tax base, uncommonly high taxes, and stalled job growth can afford such a massive public works project, he responds by saying, in effect, that such picayune concerns are above his pay grade. “I don’t know all the details—I’m not a technocrat,” DiBerardinis says. “The first step is having the conversation and building the coalition for change. You’ve got to know where you’re going first.”

There’s that old poetry/prose conundrum. The truth is, if you’re seeking a legislative post, you have to be more than a pundit. You also have to demonstrate you can get stuff done, which means having a plan.

![]()

But this is City Council we’re talking about, and wouldn’t you rather have someone running for it with big, bold ideas, no matter how challenging or impractical? As opposed to, say, a candidate who stays true to the body’s old merely transactional playbook? There are plenty of case studies that illustrate the backwards, small-minded ways of Council—the Councilmanic Prerogative embarrassments, John Dougherty’s alleged weaponizing of its members to serve his narrow interests, Darrell Clarke’s refusal to even hold hearings on the selling of the Gas Works in 2015, a potential $1.5 billion windfall—but it’s actually the smaller indignities that get me most worked up. Like the story of Bill Miller’s tuxedo.

A little over a decade ago, the late Miller, who had a six figure communications contract with Council, found himself preparing to go out on the town on New Year’s Eve, when he realized his tuxedo was at the dry cleaner’s. And they were closed. So what did Miller do? He called then-Councilwoman Marian Tasco, whose district was home to the dry cleaner’s business.

The owner lived in the suburbs, and imagine his surprise when he got a call from the Councilwoman on New Year’s Eve, directing him back into the city so her fellow insider could be properly decked out in black tie. It’s a funny story, but also a terrifying one. Think of it: Would a small business owner dare refuse a “request” to schlep back to work from someone who could zone his business out of existence? I always think of Bill Miller’s tuxedo when contemplating just how out of line Council is with our values. Who knows how many such stories there are?

So, yes, Justin DiBerardinis might be floating some pie in the sky ideas, and here’s hoping he thinks more deeply about how to fund them. But better that, better a cacophony of ideas than the same-old transactional politics that has gotten us where we are, right? Better vision than cynicism, no?

That’s another lesson from DiBerardinis’ time at Bartram’s Gardens. “You don’t plant a garden for tomorrow,” he says. “Instead, you think about what you’re going to have in 25 years. Well, a city is an even more complex and organic ecosystem. You have to have a vision.”

Photo via Justin For Philly