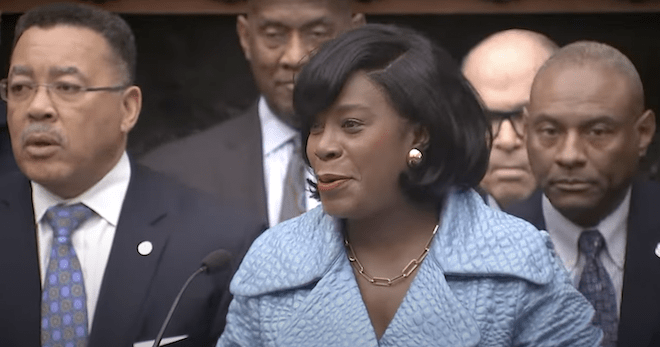

Now that Mayor-elect Cherelle Parker has gone yard with her first and most important act of actual governing — the hiring of a supremely qualified police commissioner — might there be more change in the air even before swearing-in day? Parker’s high energy public voice, such a contrast to eight years of Mayor McGrumpy, has the civic leaders I speak to cautiously excited: On the big, historically intractable problems of crime, job growth, poverty and the environment, we might just be in for a long overdue era of change.

Of course, we’ll never really make the inroads on those issues if we don’t reimagine how Philadelphia government actually works. Einstein is said to have defined insanity as “doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results,” and we may be about to find out just how deranged we’ve been.

How much can one leader’s force of will remake a sclerotic, bureaucratic, transactional culture? Yes, policy matters. But since Election Day, Mayor-elect Parker has talked about getting shit done. That’s actually the change Philadelphia most needs — a change in mindset, a change in ambition. A recognition that the unsexy blocking and tackling of politics can get government back in the customer service business.

As one civic leader observed to me about a year ago, “This administration sure loves its pilots.”

That’s why Mayor Parker should put under a microscope the city’s addiction to pilot programs. For eight years, Philadelphia has been an adept practitioner of what has come to be called “pilot purgatory,” as described in a new report put out by Jacobs Technion-Cornell Institute at Cornell Tech and the New York City Economic Development Corp. The Pilot NYC Road Map reports, for example, that, last year, some 50 out of 600 companies that applied were chosen to pilot their products through city-run programs.

In the deployment, though? Therein lies the rub.

Learn, iterate, reiterate, scale.

As author Jennifer Pahlka reminded us on our How to Really Run a City podcast, implementation is policy. Her book, Recoding America: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better is a must-read for anyone interested in making City Hall more responsive to its citizens. It essentially reaches the same conclusions as the New York City report, which finds that government focuses more on getting a pilot up and running than on tracking its long-term prospects, learning from the data, iterating and reiterating, and, ultimately, scaling a test program citywide.

In Philly too, as one civic leader observed to me about a year ago, “This administration sure loves its pilots.” It’s true; we’ve adopted program after program, complete with glowing press releases, but rarely have we grown said pilots toward large-scale adoption.

The most glaring example has been Group Violence Intervention (GVI), Philly’s version of focused deterrence policing. Far from being an experiment any longer, it’s a proven strategy that has worked in cities across the nation for decades, as we’ve covered. In fact, it worked here, under then-Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey and Mayor Michael Nutter, in a pilot Mayor Kenney shut down upon taking office. Fast forward to 2021, when Kenney brought it back — as a pilot, still. It’s worked impressively these last two years, but still hasn’t been fully scaled, currently deployed in 15 out of 21 police districts.

Parker hasn’t even placed a hand upon the Bible yet, so it’s still way early. But at least she gets that part of the gig is remaking the psyche of the city.

How many other pilot programs does the City have going? It’s hard to arrive at an exact number, in part because as The Citizen’s J.P. Romney noted in a story about a lifesaving speed camera pilot on Roosevelt Boulevard, the City has no Pilot Czar keeping track. Suffice it to say Philly’s pilots are many. There’s Pushing Progress Philly, also known as P3, which is based on Chicago’s acclaimed READI model. It involves credible outreach to high-risk young men with proven techniques like cognitive behavioral therapy and transitional jobs and job training. But, in the midst of crisis, the Kenney administration embarrassed itself by taking years to get its version up and running this spring.

We’ve got a modest Guaranteed Income pilot program — targeting all of 250 pregnant women next year — despite years of evidence that income programs work. We’ve got a smart streetlight pilot that uses sensors to check air quality and collect traffic and street activity. We’ve got a pilot proposal for year-round school, something Parker campaigned on. We’ve got a $1 million Participatory Budgeting pilot, in which citizens can vote on how a sliver of public dollars are spent.

I could go on — there’s no dearth of well-meaning pilot programs paid for by your tax dollars. But they all sort of conform to Philadelphia’s silent killer: The curse of incrementalism. When you’re in widespread crisis, maybe more than tepid test cases are called for?

Take that last one, for instance: Participatory Budgeting. Here, we give citizens a mere $1 million of a $6.2 billion operating budget to weigh in on, and we call that progress, as though it were consequential enough to rekindle a sense of trust between citizen and her government. In New York, by way of contrast, $40 million is allocated to Participatory Budgeting. Even more to the point, Boston voters went so far as to create an Office of Participatory Budgeting. Mayor Michele Wu appointed a prominent Bostonian to head it, who will work with an external oversight board comprised of citizens.

“Working with the office, the external oversight board will be tasked with submitting participatory budgeting project proposals to the Mayor for inclusion in the City’s budget,” the Mayor’s office said in its June announcement of Renato Castelo as the office’s inaugural director. “The board will also assist in the creation of a participatory budgeting rule book, which will outline the policies and procedures for the participatory budgeting process. The board will be composed of nine Boston residents with varied experience and expertise, including community investment and development, public finance, open space, urban planning, community organization and outreach, affordable housing, public education, public health, environmental protection, and historic preservation.”

The change agent we need?

See the difference between the Philly and Boston approaches? Here, we say we’ve done something in a press release. There, some actual rethinking is going on around the relationship between government and governed. It’s too soon to tell whether the Boston experiment will work or not, but at least it’s an attempt to codify into law a way to boost civic participation at a time when citizens are more jaundiced than ever, often with good reason.

The New York report is loaded with recommendations for how Mayor Adams can change government so that it scales, rather than just pilots. My favorite is its recommendation to modernize the procurement process. You know the way it traditionally goes: Cities announce the solution they’re looking for, and vendors bid.

The Pilot NYC Road Map suggests adopting a “challenge-based procurement” model instead, in which the city announces a problem and invites creative ideas to solve it. It’s a concept Gov. Gavin Newsom enacted in California with a 2019 executive order establishing a new type of technology procurement, a “request for innovation” that has helped turbocharge the state’s growth in technological innovation. It’s also another model Philly has deployed on a small scale, and then let fall by the wayside.

Do you remember Michael Nutter’s uplifting inaugural address theme in 2008? It was, “New Day, New Way.” In that, he was presaging Obama’s hope and change mantra that took the country by storm a year after Nutter’s election.

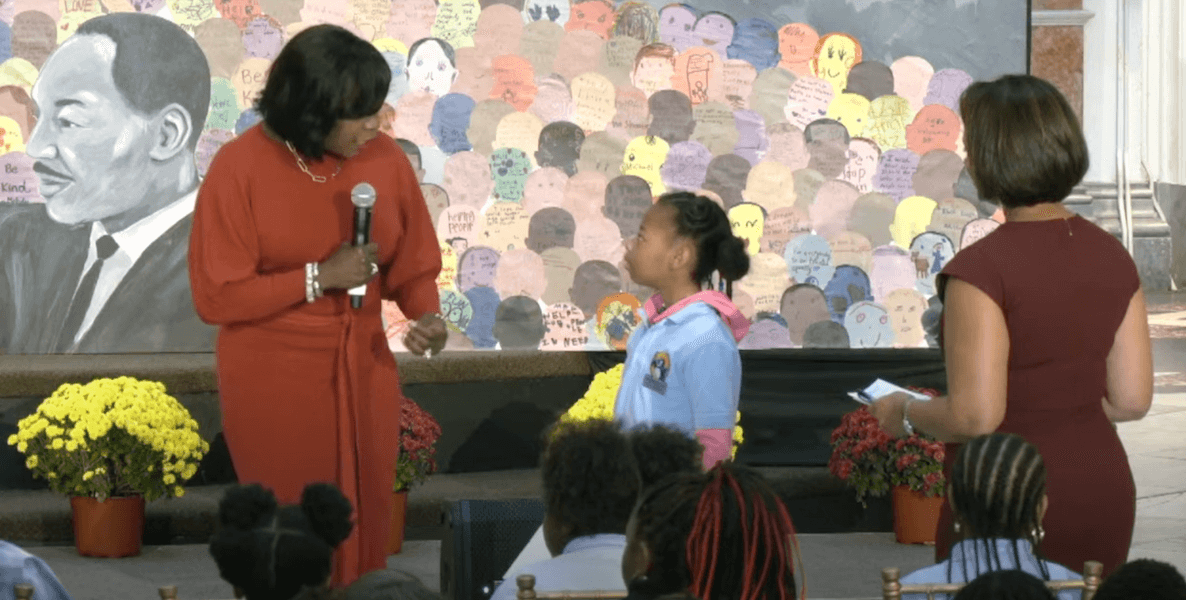

Parker seems keenly aware she has a similar opportunity to capitalize on just such a moment. Two times in a row now, she has signaled to us that there’s going to be a newly collaborative spirit at City Hall. One was when she politically astutely shared the election night spotlight with Kenyatta Johnson, who will likely be her Council President; the other during the press conference naming Kevin Bethel police commissioner, when she called to the podium new FOP head Roosevelt Poplar for his endorsement of her choice.

Parker hasn’t even placed a hand upon the Bible yet, so it’s still way early. But at least she gets that part of the gig is remaking the psyche of the city. Hiring well goes a long way toward doing that. But so would a sober analysis of the hodgepodge of pilot programs currently laying claim to the City’s budget.

After all, Philly has a historic $6.2 billion budget — that’s a whopping 63 percent increase over the life of Kenney’s mayoralty. And that doesn’t even take into account the millions coming from, respectively, the Inflation Reduction Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and the CHIPS and Science Act — all of which seek to fund innovative solutions to urban problems, particularly of the climate variety.

A chief executive who looks at pilots and makes the tough decisions to scale some while abandoning others? Who reshapes them in a way that makes citizens feel like their government is actually being returned to them? That’s a change agent.

![]()

MORE ADVICE FOR MAYOR-ELECT CHERELLE PARKER