The 2020 election is all about turnout. We’ve heard it over and over.

What we don’t hear as much about is the step that happens first: voter registration.

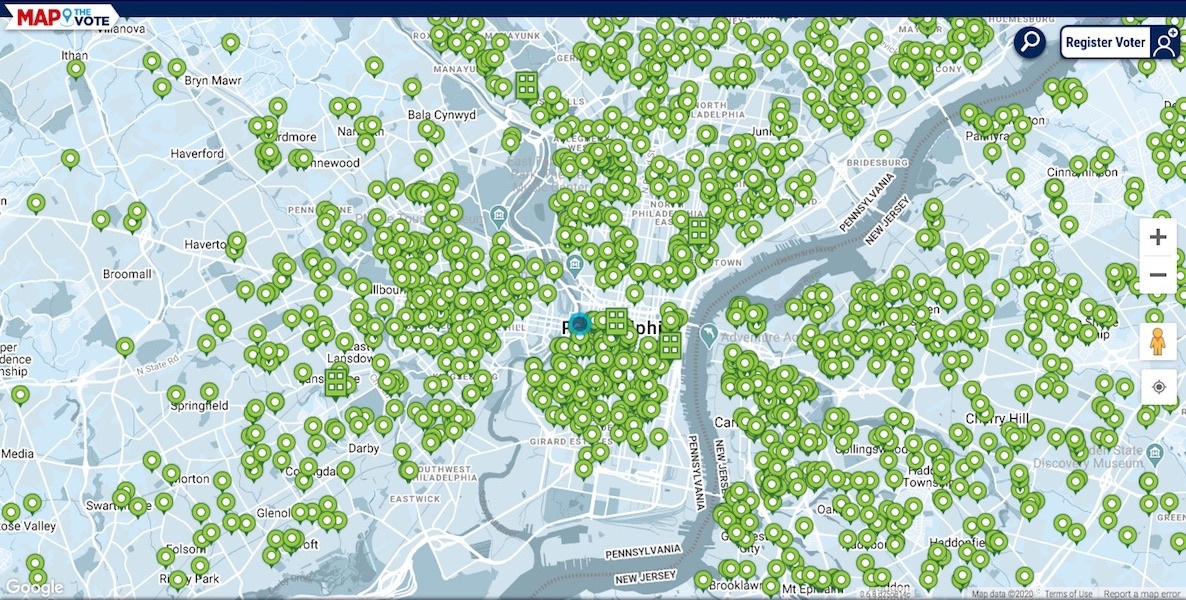

According to the non-profit Map the Vote, at least 40,000 eligible Philadelphians are currently unregistered. If things stay that way, those citizens will not be able to cast a ballot in the April 28 primary, or in the general election in November, what is arguably the most important presidential race in a generation.

![]() Some of these people have no interest in voting. (They should.) But, according to a 2017 Pew survey, the majority of the group is made up of residents who haven’t registered for other reasons, including “I intend to register, but haven’t gotten around to it” (27 percent).

Some of these people have no interest in voting. (They should.) But, according to a 2017 Pew survey, the majority of the group is made up of residents who haven’t registered for other reasons, including “I intend to register, but haven’t gotten around to it” (27 percent).

Unregistered voters include folks who recently moved and forgot to update their registration; newly eligible 18 to 20 year olds who have not yet registered; and previously incarcerated people—including those on probation or parole—who don’t think they can register. (They can.)

According to the same survey, 62 percent of these eligible but unregistered voters have never been asked to register.

This is where Map the Vote comes in. The Texas-based nonprofit rolled out its crowdsourced registration app nationwide last year, to map where likely unregistered voters live, and provide tools to help neighbors or organizations get them on the voter rolls.

“We registered about 156,000 new voters in six weeks, 112,000 of which went on to vote,” Jasinski says.

In Philly, Map the Vote shows that, though the highest populations of unregistered voters live in Center City (likely due to people moving in and out of apartments, and because of our inaccurate voter registration lists), there are hundreds of unregistered voters in every single neighborhood around town. The app makes it simple for everyday citizens to do something about it.

Here’s how it works: Open Map the Vote on your phone and you’ll see a mess of green dots appear around your location, each representing a likely unregistered voter at a specific address.

Click on a dot and you’ll see the address, along with a script that helps you start the conversation and provides tips for what to say to certain common responses like, “I don’t have time,” or “I don’t vote.”

You can check a person’s registration status right in front of them, and help them fill out the voter registration application online. You then update the app so other canvassers can see your progress. It’s a useful tool to help organizations already working on voter registration, too.

![]() The tool was created in 2018 by Register2Vote, a nonprofit co-founded by Jeremy Smith, former Army engineer officer and voter protection activist, and Madeline Eden, election security analyst and CTO of Blockchain Innovation, Inc., to apply tech solutions to the crucial, oft-neglected issue of low voter registration in Texas.

The tool was created in 2018 by Register2Vote, a nonprofit co-founded by Jeremy Smith, former Army engineer officer and voter protection activist, and Madeline Eden, election security analyst and CTO of Blockchain Innovation, Inc., to apply tech solutions to the crucial, oft-neglected issue of low voter registration in Texas.

“People consider it a red state, but the reality is it’s not even remotely a red state,” Eden says.

“It’s basically a state where nobody votes.”

Just 55 percent of Texans are registered to vote, which is in part because the registration process is exceptionally convoluted.

Unlike the 38 states that offer online registration, Texas requires residents to send a physical paper form to their county voter registrar. To get that form, you have to go to the voter registrar’s office in person, or print one out online and mail it in—and it’s not effective until 30 days after it’s accepted.

If you’re a Good Samaritan looking to help voters register, you must be a volunteer deputy registrar, which requires training and a license renewal every two years, and is only valid in one county. (Which makes us Pennsylvanians—with our first major voting overhaul passing last year—look pretty darn spoiled.)

Register2Vote created a workaround to give Texans the most simplified way to get registered: They built a data set so voters could check their registration. If they weren’t registered, they’d fill out their information online, R2V would print out the form and mail it with a stamped envelope made out to their county registrar’s office—to be signed off on and popped back in the mail.

![]() And though maybe it sounds like only a slightly less cumbersome method, small, convenience-focused improvements can go a long way. And the R2V team realized they could do even more if they could target likely unregistered voters—another issue that tech could work to solve.

And though maybe it sounds like only a slightly less cumbersome method, small, convenience-focused improvements can go a long way. And the R2V team realized they could do even more if they could target likely unregistered voters—another issue that tech could work to solve.

In most states, voter registration lists—which include names and addresses—are available to the public and/or political organizations. To build a data set in Texas, the R2V team cross-referenced that list with U.S. Postal Service’s address database.

“If we have an address where there’s not someone registered and it’s a residential address, then it stands to reason that there are unregistered people at that address,” Eden says. They also used the national change of address data to identify likely unregistered voters.

They built a user-friendly mapping tool, recruited canvassers across the state, and the registration forms started pouring in.

“We filled this warehouse with hundreds of volunteers who were printing and stuffing envelopes,” says Christopher Jasinski, client success manager for Map the Vote’s umbrella organization, Civitech.

The effort required all the envelopes in the state of Texas—volunteers drove to stores across state lines and stuffed their cars with them. “We registered about 156,000 new voters in six weeks, 112,000 of which went on to vote,” Jasinski says.

Philadelphia could have the power to sway the state: President Trump, the first Republican to win the state in almost 30 years, won Pennsylvania by just 44,292 votes in 2016—a few thousand more than the number of unregistered Philadelphians.

Following the midterms, they wanted to make a bigger impact. They expanded the map across the country last year and started partnering with organizations in other states to lead canvassing efforts with Map the Vote.

Pennsylvania falls somewhere in the middle in terms of percentage of registered voters at 66 percent. (On the low end are Hawaii, California, Texas, New York and Florida—all between 50 and 55 percent; and on the high end, Maine, Mississippi, Michigan, Kentucky and North Dakota, which range from 70 to 77 percent.)

And thanks to new voting laws passed last year, we also fall in the middle in terms of ease of registering and voting, with online registration and no-excuse vote-by-mail.

Voter rolls are messy and inaccurate, because people die or move away. (Voters—who don’t cancel their registration after moving out of the state—are removed after not voting for five consecutive elections and two federal elections.)

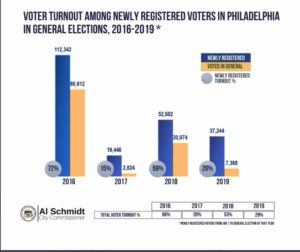

But turnout in Philly is, by any measure, unimpressive, hovering between 28 percent in last year’s mayoral race and around 66 percent for the 2016 election. New registrations could be the bump we need this year.

As in Texas, research shows that newly-registered citizens are inclined to vote in their next possible election. And Philadelphia could have the power to sway the state: President Trump, the first Republican to win the state in almost 30 years, won Pennsylvania by just 44,292 votes in 2016—a few thousand more than the number of unregistered Philadelphians.

But registering to vote is not just about elections. It’s about making it known to politicians that we care. The more of your neighbors are registered to vote—and showing up at the polls—the more politicians will pay attention to your community. Want more funding for your local playground? More attention from police? Better zoning rules for your local business strip? Then you need your neighbors to be politically active.

Stay tuned for word about a Citizen Register Philly event that will be a chance for individuals and organizations to learn more about Map the Vote and get canvassing tips for registering your neighbors (or heading out to neighborhoods where it’s most needed). In the meantime, you can check out Map the Vote here to get started on your own.

The reward for your efforts? Democracy itself.