There’s a corporate executive I know — great guy. Back when he was promoted from worker bee to the C-Suite, he was confronted with a challenging adjustment. From cocktail receptions to boardrooms, he felt … not quite right. He was out of sorts, impostor-like, and it showed in his work. In short order, it felt like he was failing in this all-important new role. Finally, a mentor opened his eyes.

“You’re not just the same guy with a different title now,” she told him. “People expect something different from you now. They’re all watching you. You have to embrace that you have a bigger responsibility here.”

It woke my friend up to his new reality, and he began the process of creating an executive persona — walking into rooms with swagger, while keeping in mind the degree to which all of the various constituencies he now served hung on his every word. He started infusing every day with the driving force of that bigger sense of responsibility.

Here’s hoping that our city’s new political leadership is reacting to this exciting moment of change with the same type of intentional introspection. After all, no one who becomes mayor or council president has ever done it before. (Notwithstanding attempts a little over a decade ago to draft the legendary Ed Rendell, in his post-governorship, to run again for mayor.)

Mayor Parker has infused her public statements with a “we’re all in this together” sense of hope and energy. At her last press conference, she referred to the citizens of our city as her “customers.” That’s the sign of a burgeoning leader widening the aperture of her lens.

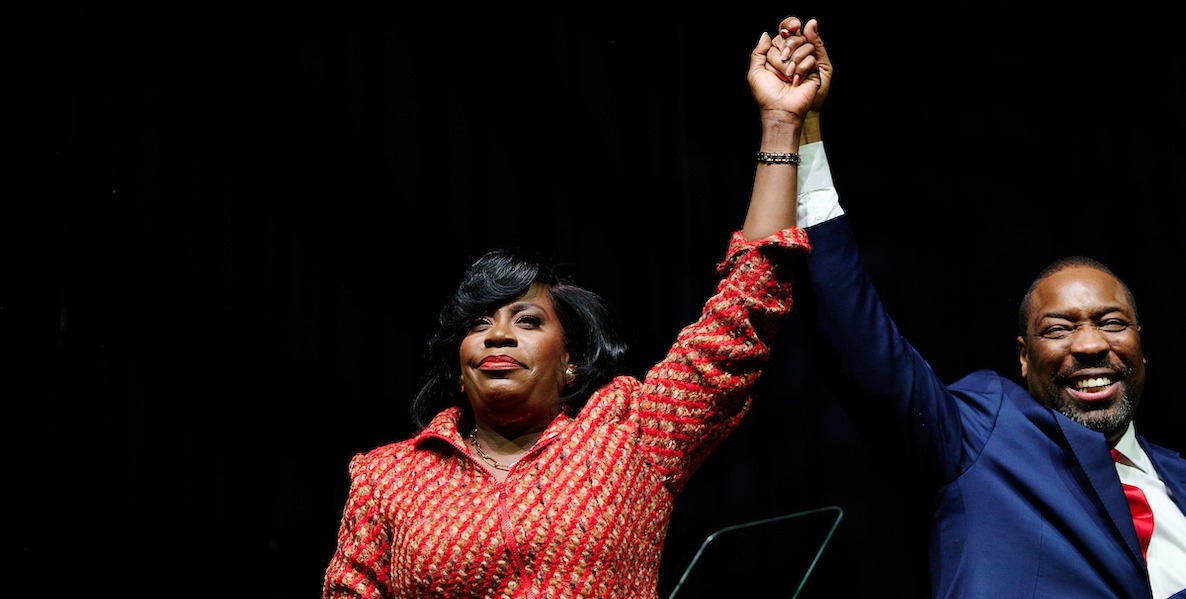

Our new set of leaders — Mayor Cherelle Parker, City Council President Kenyatta Johnson and Council Majority Leader Katherine Gilmore Richardson — have all cut their teeth as legislators. That’s a vastly different role; more deliberative, less action-oriented, more distanced from the psyche of one’s city. Moreover, in the case of Parker and Johnson, both were district councilmembers, accountable not even to the whole city, just their little corner of it.

One of the reasons this moment is so interesting in our city’s history is that you get a sense that all these leaders are aware of the stakes and are striving to fit into their new roles. Mayor Parker has infused her public statements with a “we’re all in this together” sense of hope and energy. At her last press conference, she referred to the citizens of our city as her “customers.” That’s the sign of a burgeoning leader widening the aperture of her lens. (And if she really wants to instill a customer service ethic in her government, she’ll hire Brian Elms, the municipal customer service whisperer we hosted on our How to Really Run a City podcast.)

And Council President Johnson? Well, after I aired my doubts about him — cautioning that he not be Darrell Clarke 2.0, a master of mere transactionalism — he gave me a call. “I think we should get together,” he said. “You may have some ideas I should steal.”

It’s a call I never got from Clarke or, for that matter, Jim Kenney, who wouldn’t even talk to me when we were side-by-side at a urinal. (I would have had mad respect if he’d quipped, “You gonna piss on me here, too?”) Our talk was off-record, but suffice to say that Johnson exudes a sense of curiosity and openness that can only aid him as he tries to lead a legislative body into confronting long intractable problems.

Perhaps most encouragingly, I hear that there’s no daylight between Johnson and Parker. Obviously, it’s awfully early, but at least they realize that their political fates are inextricably intertwined. Already, it looks like the days of having dueling lobbyists in Harrisburg are about to be over — one reporting to the Council President, the other to the Mayor. Two district councilmembers now in charge of the city government are finding common ground in conducting their public affairs as though we’re one city.

Some examples to mind

Both would be well-advised to look elsewhere for object lessons on how to handle the growing pains of executive leadership. In Chicago, new Mayor Brandon Johnson is modeling what not to do. Dude just got elected last year and is already languishing at 22 percent in the polls — amid talk of a recall effort. He’s made some noticeable blunders — most along the lines of, you guessed it, not governing the whole city. A former member of the Chicago Teachers Union, he hired one of its executives to handle the city’s negotiations with that very same union and, as City Journal has chronicled, began said negotiations by giving up significant leverage right off the bat.

No single interest group — whatever the merits of their cause — should have outsized influence in any administration. In Pittsburgh, Mayor Ed Gainey has essentially handed his mayoralty over to the SEIU (which Kenyatta Johnson has long been aligned with, particularly at the airport), not unlike how Mayor Kenney allowed the criminal labor leader John Dougherty free reign here.

Moreover, if leadership is about intuiting the concerns expressed around your voters’ kitchen tables, Johnson didn’t get the memo. When groups of teenagers vandalized storefronts and beat up passersby, he said he was not going to “demonize youth who have otherwise been starved of opportunities in their own communities.” When asked when Chicago’s rampant crime would come down, he doubled down, saying it depended upon when poverty and its trauma in neighborhoods could be addressed. This is how Democrats lose, folks.

The pragmatic progressive leader wouldn’t shy away from combating poverty — but would also say, as Parker has, that there are no moral equivalencies when it comes to providing consequences for those who break the social contract.

In New York, meanwhile, Mayor Eric Adams is also down in the polls, fighting with the Biden administration over the influx of immigrants diabolically being shipped to his sanctuary city by the likes of Texas Governor Greg Abbott. Ominously, he’s found himself on separate pages with his Council Speaker, Adrienne Adams, and Public Advocate Jumanne Williams. They orchestrated an overwhelming override of Adams’ veto of a pair of police reform bills, and it’s been an ugly public spat. Now, primary challengers, smelling blood, are lining up to potentially take Adams on when he runs for reelection.

Notice what’s going on here: A progressive is failing in Chicago, and a centrist is floundering in New York. You’ve heard it here before: Governance in cities doesn’t break down along ideological lines. Note to Parker and Johnson: What matters is, can you work with others? Can you put your voters’ interests first? Do you sound like the people who elected you? At first, Mayor Adams’ late night partying ways at Osteria La Baia were a nice contrast to his dour, anti-social predecessor, Bill de Blasio. Now it just seems like his lifestyle is out of touch with the lives of his struggling constituents.

“When people show you that they are not rowing in the same direction, you do what we do, and you call them in at four o’clock on a Friday, and you thank them for their service, but their season here has passed.” — former Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner

You know who has been killing it? Mayor Karen Bass in Los Angeles, who also joined us on our podcast. A new poll finds her cruising along at 59 percent job approval, while her Council — which, like Philly’s, has long been mired in public corruption trials — is at 29 percent. Support for the progressive DA, George Gascon? Cratering, at 26 percent.

Voters like the job Bass is doing, yet by a two-to-one margin they think the city — of which she’s been mayor for a year — is on the wrong track. What accounts for that? Well, Bass is doing what she said she was going to do, having sheltered some 20,000 homeless Angelenos to date. More important, she’s brought what Zen practitioners call “beginner’s mind” to her confrontations with her own bureaucracy. “Just tell me if it’s legal,” she’s told her staff, before embarking on the common sense reform du jour before her.

It’s easy for a mayor to be overtaken by a set of crises. (See: Kenney, Jim.) Bass hasn’t let her agenda be swallowed up by storms, mudslides, murder sprees, or Hollywood going on strike. Robin Kramer, chief of staff to two former LA mayors, tells CalMatters that chief executives historically seek to devote no more than half their time responding to the issue of the day so they can focus on driving their agenda. Bass, who meets on homelessness every day, has modeled such focus.

Leadership growing pains

Here in Philly, there will be growing pains as Parker and Johnson acclimate to the enormity of their new roles. Parker, for instance, has been slow to fill out her team — a legislator’s pace perhaps. Of her appointments, all are local. (What are the chances that the absolute best person for each and every job was the person who basically was right there all along?) One transition team member reports that, unlike Mayor Nutter’s transition team in 2007 — which penned position papers and interviewed candidates — his transition committee took part in two Zoom brainstorming sessions, with Parker’s representatives taking notes. That’s a conscious choice — but maybe not one a practiced chief executive would make.

That said, Parker’s public rhetoric has been dead on — she says what her voters are thinking — and she’s hit many of her appointments out of the park: Police Commissioner Bethel is a consensus all-star, Managing Director Adam Thiel has a stellar reputation, and, while the Commerce Department seems like a strange landing spot for her, Alba Martinez is a superstar.

The recent kerfuffle over information flow, while appearing Pravda-like, seems overblown, something only media types care about. So what if all department communications have to run through the mayor’s comms department? The good government answer to that policy is to rid the government of all those (now) do-nothing department comms offices!

But it could point to a bigger problem not unrelated to what seems to be the parochial streak in Parker’s hiring. The best chief executives hire great people, let them do their job, and then shamelessly take credit for them. Insecure chief executives, however, tend to micro-manage. (I loved Jimmy Carter, but when it was reported that he was overseeing who could sign up to use the White House tennis courts it pointed to some deep managerial issues).

When you’re the mayor, you have close to 30,000 employees and a whole city looking to discern direction from your every word. That’s why it mattered when Jim Kenney’s chief of staff, asked if anyone would be fired that time the administration couldn’t find $30 million of its own money and hadn’t reconciled its bank accounts in seven years, replied: “No, that’s not how we operate.” Leaders must establish cultures of accountability early on, as now-former Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner points out.

“When people show you that they are not rowing in the same direction, you do what we do, and you call them in at four o’clock on a Friday, and you thank them for their service, but their season here has passed,” he said.

Finally, a successful chief executive doesn’t just manage and inspire — he or she also challenges. Remember JFK’s inaugural address? “Ask not what your country can do for you / Ask what you can do for your country.” Philadelphians of good will are dying to be asked to do good. During the primary election, I helped put together a small group of committed civic leaders to hear from — and advise — the candidates. Each candidate pledged that, if elected, they’d tap into the expertise of those in that room, and many others like it. A mayor and council leader should be reaching out to business and civic leadership not to placate check-writers, but to urge them to put their smarts to use in pursuit of the common good.

And the same goes for the everyday taxpayer. Kennedy had the Peace Corps; Clinton had AmeriCorps. These were more than just smart policies; they were calls to action that, in effect, said to each and every citizen, You have more power to change your environment than you think. Just this week, a local thought leader floated an innovative idea: How about establishing special services districts in every neighborhood throughout the city? What if everyday citizens got paid some nominal fee to beautify their own streets? That would be tantamount to the mayor and council president saying: Don’t passively wait for government to lead. We’ll help you get off your ass and make your city better. Now that would be leadership.

![]() MORE ON POLITICS FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE ON POLITICS FROM THE CITIZEN