Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,the blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere the ceremony of innocence is drowned; the best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.

—W.B. Yeats, “The Second Coming,” 1920

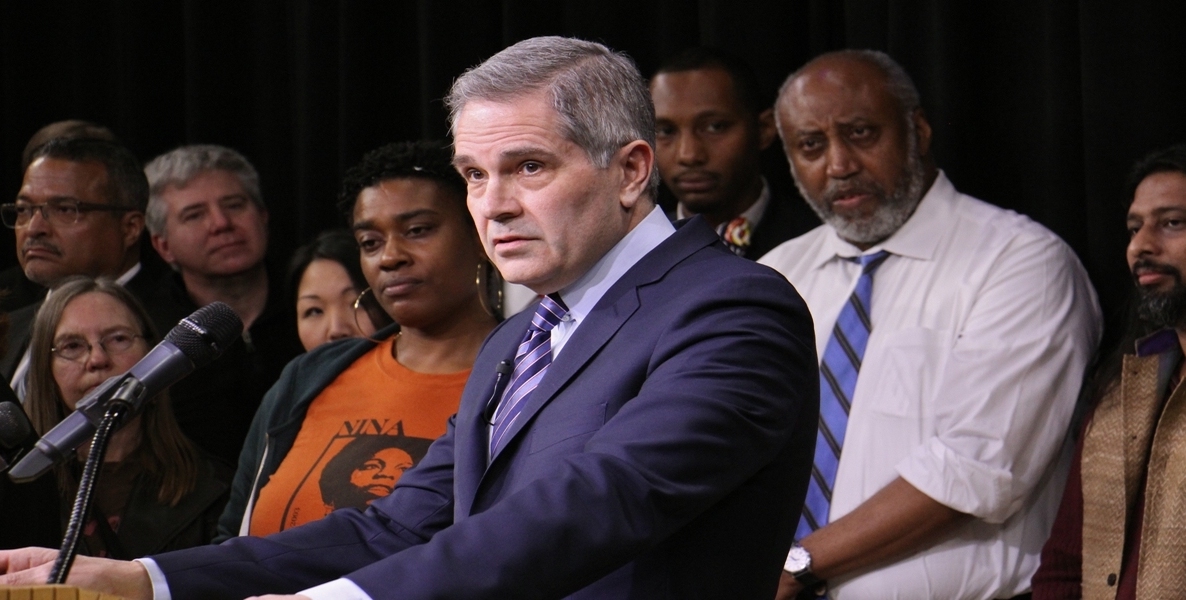

Just this week, Larry Krasner made headlines when he charged Ryan Pownall with murder and related offenses—the first time an on-duty Philadelphia police officer has been charged criminally in nearly two decades. Pownall, who was dismissed from the force last year over the shooting in question, seems like the poster child for cops run amok: Last month, Philadelphia Weekly and City & State PA revealed that he’d been the subject of 15 civilian complaints in five years, the third highest total on the force. (Makes you wonder what’s up with the first two, David Dohan and Marc Marchetti.)

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article on CitizenCast below:

But even when Krasner gets it right—as in this case—his predilection for ideology calls into question his motives. In his press conference announcing the indictment, Krasner wasn’t just following the evidence in one particular case, Joe Friday-like, and putting away a bad guy; he was fixing a corrupt system. “This is a city, like many other American cities, where there has not been accountability for activity by police officers in uniform, especially when that activity involves violence against civilians,” he said.

Let’s be clear: Krasner is right that bad cops shouldn’t be above the law, here or anywhere else. But his past vilification of police (the “F@#k the police” chants at his headquarters on election night, which he defended as a First Amendment right) and of his own District Attorney’s office (as a candidate, he called it a “coverup operation”) doesn’t exactly inspire confidence that he’s an honest broker in our finger-pointing political standoffs. In this and countless other examples, Krasner’s public pronouncements have been characterized by the condition that, more and more, paralyzes our politics: A true believer’s zero sum sense that, “I’m right, and you’re wrong.”

Let’s look at one such case study. What is it, after all, with Larry Krasner and the victims of crime? For months now, victims, and families of victims, have come forward, making headline after headline, with complaints I can’t recall ever hearing about a prosecutor. They have been uniquely personal, and have come from a diverse pool; one day, it’s the family of a slain black police officer, complaining bitterly that they weren’t consulted about a plea deal made with their loved one’s assassin. The next, it’s the mother of a Rittenhouse Square developer stabbed to death on a city street claiming to have been manipulated by the DA, calling him “intellectually dishonest.” The Inquirer has chronicled each case, but the sheer litany of them begs the question: Can they all be wrong? Does Larry Krasner, long a criminal defense attorney, have a blind spot when it comes to the victims of crime?

Most prosecutors see the victim as the proxy for all of us; they do, after all, represent “the people.” The open question is, does Krasner see it that way? Or does he just think of victims as just another interest group to be managed?

It’s a valid question, as Krasner has tacitly acknowledged by addressing the issue last month when he launched Philadelphia CARES, a $1 million program of support for the families of homicide victims. But any consideration of Krasner and victims ought to go deeper than any one program, or any one case study. For Krasner’s blind spot is just a symptom of this greater malady, the curse that the poet Yeats described 98 years ago. It’s the curse of ideological purity. No matter the issue, no matter the side, we seem surrounded by “with us or against us” certainties—nuance and reasonableness and doubt be damned.

When Krasner, responding to complaints from the family of a defendant, recently dispatched an aide (the same aide to whom he was once financially indebted) to a Philadelphia courtroom to try to overrule the judge, the defense and the prosecution—all of whom had agreed to clear the courtroom so as to avoid witness intimidation—it was the latest indication of an ideology that seems to channel Mick Jagger circa 1968: “Just as every cop is a criminal, and all the sinners saints.”

speak with Chris Hayes about ending mass incarcerationListen to Krasner

In his recent podcast interview with MSNBC’s Chris Hayes, Krasner places himself at the center of a social justice “movement” among prosecutors, a word—especially in the “just the facts” world of law enforcement—that connotes adherence to orthodoxy. Indeed, many who join Krasner on the social justice warrior left think we’ve taken the notion of “victims’ rights” too far. They point to an article in The New Yorker last May by Jill Lepore, headlined “The Rise of the Victims’-Rights Movement,” that traces how we got to what some saw as a ludicrous display before the nation in a Michigan courtroom last winter. Former Olympic gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar was convicted of sexually assaulting seven women, and had already been sentenced to sixty years in prison on child pornography charges; yet, on live TV, no less than 156 women were permitted to make heartrending victim impact statements, detailing crimes Nassar hadn’t even been charged with.

I have no idea if Krasner even read Lepore’s piece, but there’s no question that a frequent criminal justice critique of the left is that old-school prosecutors have long been too sensitive when it comes to victims, and, as Krasner pointed out ad nauseum during his campaign, too driven to convict defendants “at any cost.” In that context, the complaints detailing a dismissive attitude on the part of Krasner toward victims might not be blind spot so much as the byproduct of a rigid worldview.

There’s a difference between agreeing that the victim impact statement parade in that Michigan courtroom went too far, and actually being anti-victim. Most prosecutors see the victim as the proxy for all of us; they do, after all, represent “the people.” The open question is, does Krasner see it that way? Or does he just think of victims as just another interest group to be managed?

Philadelphia spends over $45 million on violence prevention programs of dubious effectiveness, as the Inquirer’s Helen Ubinas has unearthed. Yet focused deterrence, which pretty clearly works? We spend $130,000 on it.

In the Hayes interview, Krasner conveniently advances another view that is taking hold on the left. Asked by Hayes about the stunning decrease in crime nationally since the early ‘90s—Hayes calls it a “miracle”—Krasner says, essentially, it’s all a mystery. “You can get a bunch of criminologists in a room and have them talk to each other, and there is no consensus on it,” he says, “but we do know that there’s been a decrease in crime.”

That’s convenient if you’re Krasner, because maintaining that we don’t know why crime has dropped is not that far from asserting that we don’t know how to decrease crime rates. For a district attorney, such a throwing up of hands is a good way to avoid being held accountable. There’s one problem: We do know what works.

“We’ve had improvements these last 20, 30 years in focused and targeted precise policing that has helped create a more secure society,” says Temple’s Dr. Jerry Ratcliffe, professor of criminal justice at Temple University and author of Reducing Crime: A Companion for Police Leaders. Ratcliffe runs through all the innovations in policing that have contributed to lowering crime rates: Crime mapping, policing hot spots, community policing, problem-oriented policing. Locally, programs like Operation CeaseFire and Focused Deterrence have succeeded, yet we don’t invest in them—in part because our public safety debate is characterized by ideological shibboleths rather than fidelity to empirics.

Focused Deterrence makes for a fascinating case study. Ratcliffe says that 6 percent of the population commits 60 percent of the crime, and police can identify at least half of those perpetrators. Under focused deterrence, law enforcement targets that known population—convening them to both serve notice (“we’re watching you”) and offer social services. It’s the opposite of zero tolerance; neither right nor left, it’s just smart. It’s the brainchild of renowned criminologist David Kennedy, and it’s been proven effective across the nation in lowering crime rates.

More stories about Larry Krasner Read More

Here, during the campaign for District Attorney, Krasner was largely dismissive of most strategies not associated with his criminal justice reform agenda. Only one candidate, Jack O’Neill, consistently held up focused deterrence as an innovation worth our investment; in three South Philly police districts, the strategy has contributed to a 35 percent drop in shootings. Philadelphia spends over $45 million on violence prevention programs of dubious effectiveness, as the Inquirer’s Helen Ubinas has unearthed. Yet focused deterrence, which pretty clearly works? We spend $130,000 on it.

“Our government has invested in gun violence programs based on what feels good, not based on evaluating what works,” Ratcliffe says. “It would be a good idea to invest in finding out whether what we’re sinking our money into works or not.”

So what does all this have to do with Krasner? Well, what if the movement he’s coming to represent isn’t social justice, per se, so much as a new type of know-nothingism? You would think, listening to Krasner and Black Lives Matter, that the way we policed in the 1990s was simply the product of racist policies. The truth is more inconvenient than that. The Left pilloried Hillary Clinton in 2016 for her husband’s 1994 crime bill, but what went unmentioned—and continues to be glossed over—is that that legislation came about at the behest of African-American politicians, like the Congressional Black Caucus and mayors like Baltimore’s Kurt Schmoke, who had seen what exploding crime rates had wrought in inner city communities.

Krasner’s blind spot is just a symptom of this greater malady, the curse of ideological purity. No matter the issue, no matter the side, we seem surrounded by “with us or against us” certainties—nuance and reasonableness and doubt be damned.

Back then, Congressman Charlie Rangel talked about how being able to walk safely on urban streets was actually a civil rights issue. Fast forward to today, when our homicide rate is up 8 percent this year, after jumping 15 percent last year. Perhaps Krasner needs reminding that job one of the city’s top law enforcement official is to keep the citizenry safe, especially African-Americans, who are disproportionately the victims of crime.

Tell Larry Krasner how he’s doingDo Something

“The fundamental cause of the trouble is that in the modern world the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt,” wrote Bertrand Russell. Well, Larry Krasner is a smart guy, but what’s missing so far from his tenure as district attorney is also what’s missing from our politics. It’s what Russell puts his finger on: A sense of doubt. Our politics are full of resentment and rage, and elected leaders like Krasner who value being right over being effective fuel the divide.

When Krasner responds to reports of a 5-year-old being repeatedly raped by an undocumented criminal by ludicrously blaming Trump, when he disrespects victims or treats them like an annoyance to be handled, and when he implies that success in fighting crime is essentially a crapshoot, ignoring decades of data-infused innovations, our district attorney reveals himself to be blinded by ideology, when what we need is a practical problem-solver.

Photo by Kristi Petrillo