Looking back, getting dumped was one of the most fortuitous things to happen to Jennifer Weiner.

She was in her twenties, working as a features reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer, and once her boyfriend was out of the picture she found she had lots of time to focus on writing fiction. She was working on the manuscript that would become her first novel, Good in Bed, a romp about an unlucky-in-love woman whose life takes a drastic turn after an ex-boyfriend publishes a story about her in a national women’s magazine.

“I had an abundance [of time] because of the no boyfriend thing,” she says. “I loved the reporting I was doing during the day; I loved coming home and writing fiction.”

It’s only now, looking back on her experience as a best-selling novelist and 54-year-old mother of two, that she realizes how privileged she was. The first book’s meteoric rise on the New York Times bestseller list ensured that when she had kids she’d have the money she needed to pay for childcare so that she could write dozens more books. She needed the time to write so that she could have the incredible career she has today.

“I just think how impossible it would have been if I’d had kids at the time. Or if I’d had a job that just left me so exhausted by the time I came home at the end of the day that I couldn’t do anything but sleep or [if I was doing] the five to nine after the nine to five that women talk about … the laundry and the cooking and the cleaning and the meal prep and scheduling,” she says.

That’s why Weiner is trying to make it a little easier for other women to juggle being a writer alongside busy careers and home lives. She’s partnering with Blue Stoop, a Philly-based literary arts nonprofit, to launch a fellowship to provide mentorship and financial support to six, women-identified writers. The application opens today.

Supporting emerging writers

Weiner got the idea for the fellowship after watching the publishing industry spiral after the publication of American Dirt, which was widely criticized by readers of color for its depiction of Mexican migrants. The book’s author, Jeanine Cummins, is not Mexican, and many felt she treated her characters as stereotypes and reveled in their pain. Others pointed out the book is rife with inaccuracies. It led to a larger discussion into why the publishing industry chose to champion American Dirt in the first place.

“A lot of those conversations were happening about who’s allowed to tell stories, who is encouraged to tell stories,” she says. “[I was] looking at a whole industry and thinking what’s my piece of this? Where do I have ownership and what can I do to bend the arc in the direction of progress?”

Though women now publish slightly more than 50 percent of all books, Weiner believes they’re treated less seriously than their White male counterparts. She’s spoken out about her novels being characterized as “chick lit” and expressed frustration with critics who treat White male bestsellers as literary geniuses — and dismiss popular women writers. She’s also long been vocal about what she sees as the New York Times Book Review’s dismissal of commercial fiction.

“I just think how impossible it would have been if I’d had kids [when writing my first book]. Or …[if I was doing] the five to nine after the nine to five that women talk about … the laundry and the cooking and the cleaning and the meal prep and scheduling.” — novelist Jennifer Weiner

The situation is worse for women of color. Ninety-five percent of books published between 1950 and 2018 were written by White authors. Last year, 75 percent of books were by White authors. A number of prominent Black women who were hired with much fanfare as the publishing attempted to diversify in 2020 have since been let go, the Atlantic reported earlier this year. Book reviewers were still 80 percent White in 2019, the last year for which data is available according to a PEN America report.

These realities reinforce cultural ideas around who is allowed to take time away from work, caregiving and other responsibilities to be a writer.

“A guy will be like, I am writing a book and I need my writing time and this is what I’m doing. He won’t feel apologetic about it. He won’t feel presumptuous for doing it, for believing that he has talent, for believing that he has something to say. I think for women, it still seems really, really hard to do that,” Weiner says.

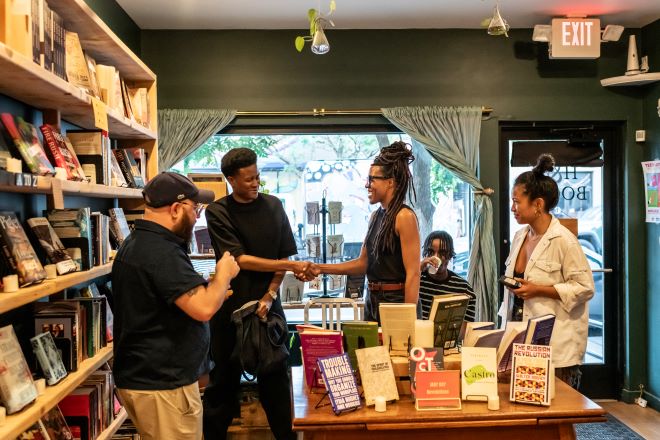

She’d long been familiar with the work of Blue Stoop, which, since 2018, has supported the city’s writers through workshops, craft classes and events. The organization, co-founded by another Philly author, Emma Copley Eisenberg, has long-prioritized supporting diverse writers and those who may face challenges breaking into the industry.

“They do such a great job of being inclusive and making sure that everyone’s got a seat at the table. Everyone’s voice gets heard,” Weiner says.

Mentorship, money and publishing know-how

Fellows will receive $5,000 and mentorship from Weiner on everything from revision and incorporating feedback to how to get an agent and navigate the publishing process. Weiner hopes it will attract writers from all different kinds of genres — romance, horror, sci-fi — she isn’t just looking for literary fiction.

The mentorship component is inspired by the challenges Weiner faced as a young writer. Once she finished her novel, the process of getting an agent and then getting it published felt daunting. She had to write query letters and learn how to sell her book — all before entering rounds of revisions with her agent and eventually selling it to a publisher.

“Everything felt like a locked room and no one gave you the key and you had to find a way into this room without exactly knowing how to do it or if you would be welcome when you got there,” Weiner says. “If I felt that way, after working in journalism, after going to Princeton, after knowing lots of writers, [then] I’m sure that people who are coming from different places are feeling that even more acutely.”

She’s especially excited to help writers understand the business side of things — something most don’t learn unless they get an MFA or move to New York City to work in publishing. She wants to advise on how to choose between agents — if a writer is lucky enough to get more than one offer — and how to distinguish between useful and harmful feedback.

“A while back there was an essay collection that was actually called MFA versus NYC where it was basically like, these are the paths to becoming a published writer; you go get your MFA somewhere or you move to New York City and you network,” Weiner says. “I think that there’s a third path, which is the DIY path where you don’t necessarily get an MFA, where you don’t necessarily move to New York City, where you just have a job, and you learn everything you can and … you just work on your craft until you have a book or a poem or a manuscript or whatever it is to take out into the world.” She wants to support writers on this third path.

Joining Philly’s community of writers

Writers can apply to the fellowship by submitting a three to five-page writing sample and filling out a brief application about their craft and how being a woman-identified person has affected their writing. (Blue Stoop’s definition of women-identified includes cisgender women, transgender women and non-binary people who feel connected in some way to womanhood.) It should only take 15 to 20 minutes to fill out. Applications close August 26.

To be eligible, writers can’t hold a masters or doctoral degree in writing, must be unpublished and can’t be under contract with a publisher. At least two fellowships will go to parents of children under 18, at least two to people of color and at least two to Philly-based writers. Weiner hopes this will help demystify publishing for groups that have been historically excluded from the industry.

“I do think that White women still have an advantage in terms of being able to walk into a room, walk into an editorial meeting, and see a lot of people who look like them and who come from the kinds of places that they did,” Weiner says. “I hope that 10 years from now, 20 years from now, 30 years from now there will be more representation and it won’t feel so overwhelmingly White.”

Accepted writers will not only benefit from Weiner’s mentorship and financial support, but also from community with one another. Julian Shendelman and Taylor Townes, co-directors of Blue Stoop, envision virtual meetups and access to recordings from Blue Stoop’s summer class series. They’ll adjust the program based on feedback from other writers.

“We hope that they’ll be able to foster connection between themselves,” Townes says. “I think being able to look at Jennifer specifically — her writing career — and seeing how she’s not only publishing work, but also creating a personality for herself on the internet … can really be powerful for women specifically, but also emerging writers.”

In the fall, Blue Stoop plans to offer classes in poetry, fiction and nonfiction. Sessions will range from two-hours to nine weeks and cost between $50 and $500, with scholarships for those who need them. They’re also planning free workshops and coworking sessions to foster community amongst local writers. The nonprofit is currently in the midst of a $20,000 summer fundraising campaign. They’ve raised just over $7,000 so far. Townes and Shendelman hope that the fellowship cohort will be able to connect with the broader Blue Stoop community.

“Writing can be a very isolating experience when you’re doing it alone in your little dark office or whatever space you work in,” Shendelman says. “You can start to really doubt yourself, and our hope is that having these simultaneous fellowships will allow those fellows to support each other, to encourage each other, and they’ll have, of course, the support of us and Jennifer Weiner to cheer them on and answer any questions when they get stuck or reassure them.”

![]() MORE ON THE PHILLY WRITING COMMUNITY

MORE ON THE PHILLY WRITING COMMUNITY