In the fall of 2017, Joseph Lindsey called his mom from a hotel ballroom in downtown Wilmington with good news: He was holding an acceptance letter with a full ride to Lincoln University.

“She was in disbelief until I got home and showed her the paperwork,” Lindsey says.

Less than an hour before, when he’d arrived at Wilmington’s first HBCU (Historic Black Colleges And Universities) fair with fellow local high schoolers, Lindsey wasn’t sure where he wanted to go to college. His mom and sister both went to Delaware State, so he liked the idea of an HBCU. But he didn’t really know much about them.

At the fair, Lindsey talked to representatives from Morehouse College, Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, and Lincoln University, and started to actually get psyched about going to college. “It was exciting to see that there’s goals to be met outside of high school,” he says.

Equally exciting: That you could be guaranteed a first step towards reaching those goals onsite in 20 minutes—which was about how long it took to get the acceptance letter and the full ride merit scholarship to Lincoln.

“It’s a tight knit community—a home away from home,” he says. “And knowing that you’re not a minority at your school? It’s just a game changer in many ways. People have your back here. That’s what’s really important.”

“That moment was exceptional for me,” Lindsey says. “I was really proud that I was able to get that scholarship.”

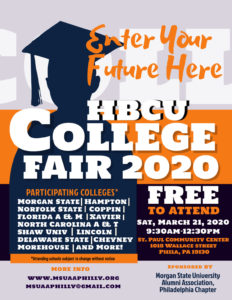

The college fair is the cornerstone of Wilmington’s HBCU Week—a series of events that aim to immerse students in the HBCU experience and to provide them with resources and tools to attend one.

“You have a group of students that didn’t think they could get in getting admitted; students who knew they were going to college but didn’t think they’d get a scholarship get a scholarship; kids who knew both and they walk away with a full ride,” says Ashley Christopher, who spearheads the initiative. “You’re watching kids’ lives get changed.”

Christopher is a practicing lawyer, special assistant to Wilmington Mayor Mike Purzycki, and an HBCU alum. She noticed that the Mayor’s Office staff employs many HBCU alumni, including Purzycki’s chief of staff, Tanya Washington, and community referral specialist Earl Cooper.

To highlight the significance of Historically Black Colleges and Universities in Wilmington, she and Cooper set out to create an event to engage a couple hundred kids from local high schools with a handful of HBCU counselors.

“As we started to promote this, it expanded almost instantly,” says Christopher. “200 students turned into 700; five HBCUs turned into 11, and that’s when Earl and I knew that this was a need that we needed to fill and continue to grow.”

And they sure have. Last year, the line-up of events included a My HBCU Experience panel discussion, the Femme it Forward Concert with Ari Lennox, and the wildly popular Battle of The Bands. And sports commentator Stephen A. Smith, who they brought on as the city’s first HBCU Week Ambassador, kicked off the college fair with a live recording of ESPN’s First Take.

The 2019 fair, held at the 76ers Fieldhouse in Wilmington, drew 3,500 students and 30 colleges. Throughout the day, colleges granted 1,200 on-the-spot acceptances and 420 scholarships (including 63 full rides) for a total of nearly four million in scholarship dollars offered.

Lindsey, now a college sophomore, attended last year’s fair as an ambassador for Lincoln University. He’s studying computer science and visual arts, competes as a thrower on the track and field team, and documents campus events as the 2022 class historian. He’s steeped in the Lincoln experience, and was excited to give his peers a window into life on campus.

![]() “I got to share it from a firsthand experience because I’m living through it,” he says. And besides answering students’ burning questions about majors, classes and his daily routine, he also described the vibe—something that surprised him when he got to Lincoln.

“I got to share it from a firsthand experience because I’m living through it,” he says. And besides answering students’ burning questions about majors, classes and his daily routine, he also described the vibe—something that surprised him when he got to Lincoln.

“It’s a tight knit community—a home away from home,” he says. “And knowing that you’re not a minority at your school? It’s just a game changer in many ways. People have your back here. That’s what’s really important.”

That feeling is key to students’ success, and in part explains the statistics: Though our country’s HBCUs make up just 3 percent of our higher education institutions, they graduate nearly 20 percent of all African American students (and 24 percent of black students with degrees in STEM fields).

And they have greater retention rates, especially with low-income and first-generation African-American students. Studies have shown that black HBCU alumni are more likely to have felt supported while in college and to be thriving after graduation than their peers that graduated from Predominantly White Institutions (PWIs).

“It taught me to be proud of who I was, that I was valuable in any room or circumstance, and it gave me a level of confidence that I need in my life going forward. I think a lot of black and brown students could use that today.”

Take it from Christopher, a double HBCU alum. She completed a bachelor’s degree in Administration of Justice from Howard University and a law degree from University of the District of Columbia.

Attending an HBCU “taught me to be proud of who I was, that I was valuable in any room or circumstance, and it gave me a level of confidence that I need in my life going forward,” says Christopher. “I think a lot of black and brown students could use that today.”

As a refresher, HBCUs were founded to educate African Americans at a time when it was illegal for black students to go to college. Though many were founded in the years after the Civil War, the first—Cheyney University of Pennsylvania then known as the Institute for Colored Youth—was founded on a farm outside of Philly in 1837, then moved to 9th and Bainbridge streets in 1866, and later to Cheyney, PA, in 1901.

![]() Ever-evolving and founded in the name of equal opportunity, HBCUs have a living legacy imperative to education in our country. And to bust a few myths, HBCUs are not second-rate institutions or party schools.

Ever-evolving and founded in the name of equal opportunity, HBCUs have a living legacy imperative to education in our country. And to bust a few myths, HBCUs are not second-rate institutions or party schools.

HBCU alumni include W.E.B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells, Jesse Jackson, Martin Luther King Jr., Barbara Jackson, and contemporaries like Spike Lee, Erykah Badu, Stacey Abrams and Kamala Harris.

And they’re not just for black students. They’ve continued to become more diverse in recent years; in 2017, 25 percent of HBCU students were not African American, compared to 15 percent in 1976. They have become integral American institutions for an even broader segment of the population.

“About once a quarter, someone asks me, Are HBCUs still relevant?” says Delaware State University President Tony Allen. “If you didn’t have us, you would have to invent us; there are very few institutions that can bring the level of diversity of experience and background, provide a comprehensive education that’s open and accessible to all, and do it for the kind of value that we provide.”

The problem is, a lot of students don’t even know attending an HBCU is an option.

Here in Philly, members of the local alumni chapter for Maryland’s Morgan State who worked in education noticed that high school counselors weren’t presenting HBCUs a promising possibility for students.

Six years ago they set out to change that and started an annual college fair at Philly’s St. Paul’s Community Center, which drew around 100 students and representatives from 26 colleges last year.

“We want to make sure that students have a fair chance in their college selection,” says chapter president Tiana Phillips. “And that what’s available to them is as diverse as can be so they can make the best decision.”

Because counselors aren’t well-educated on HBCUs, they don’t typically present them as options, and in some cases, deter interested students from attending, she says. “We’re selling state schools and community college and there’s nothing wrong with either of those, but there are other options,” says Phillips.

According to a PEW study published in 2018, of the 15 largest U.S. cities, Philadelphia has the greatest proportion of adults who never attended college: 49 percent.

Of those adults, a disproportionate number are black women. And 17 percent of Philadelphians age 25 or older have dropped out of college; half of those residents are black.

Meanwhile, 52 percent of our public school students are African American and exposing them to HBCUs presents the opportunity to stop perpetuating the statistics.

“We want them to understand the history behind the universities and know that it’s a unique experience that you’ll get there, a different kind of nurturing,” says Phillips. “If you’re the type of student that would benefit from that, then you ought to know that that’s one of the options.”

“Some of the best and the brightest attend these institutions,” says Cooper. “And these students are going to be your work force five to 10 years down the road, so let’s go ahead and make an investment in them.”

In addition to the HBCU College Fair organized by Morgan State alumni, Philly students can learn about HBCUs during college tours offered by other alumni organizations, or at the Malcolm Bernard Historically Black Colleges and University Fair—a series of college fairs throughout the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic organized by a New Jersey-based nonprofit. These are a start, a way to reach a few hundred motivated high schoolers who may hear about the fairs from their schools.

But a city-sponsored program, like in Wilmington, could pull all of these disparate efforts together in one place, allow for greater coordination with the School District, scholarship providers and students, and help give Philly students a better choice in finding a higher ed institution where they’ll thrive.

![]() DSU, Delaware’s only HBCU, has participated in the HBCU college fair since the first year. “It helped us mine a population that doesn’t always think college first, and is often underserved or overlooked by the conventional system,” says Allen. “We wanted to make sure they knew what the opportunities were that were there for them for secondary education.”

DSU, Delaware’s only HBCU, has participated in the HBCU college fair since the first year. “It helped us mine a population that doesn’t always think college first, and is often underserved or overlooked by the conventional system,” says Allen. “We wanted to make sure they knew what the opportunities were that were there for them for secondary education.”

At the 2018 fair, DSU accepted 136 of the 268 students that applied; 56 enrolled last fall.

When Wilmington student Simone Josey attended the Wilmington college fair in 2018, it opened her eyes to the academic possibilities. “Going to the HBCU fair brought to light that I didn’t realize the variety of majors offered and how many schools offered STEM majors,” she says.

She knew about HBCUs because of their renowned marching bands. “In high school, I was in marching band, but the songs we would play were like rock songs—songs that I knew, but not really songs I would listen to on the radio.”

She’d watch YouTube videos of HBCU bands playing the songs she liked. She didn’t know then that attending an HBCU would help her pursue her dream of running her own prosthetic design and manufacturing company one day.

Josey, now a freshman at North Carolina A&T State University studying biomedical engineering (and playing alto saxophone in the marching band), was one of the first recipients of the four-year, $40,000 scholarship funded by Chemours in partnership with the HBCU initiative for students pursuing degrees at HBCUs. (They’ve awarded eight such scholarships since 2018.)

Cooper and Christopher hope to continue to build these partnerships to further support students. “Our mission is not only to get kids into schools and get them scholarship dollars; but we’ve expanded that to also get them internships and job placement,” says Christopher.

“Some of the best and the brightest attend these institutions,” says Cooper. “And these students are going to be your work force five to 10 years down the road, so let’s go ahead and make an investment in them.”

Header photo courtesy Allen House Studio