Last Tuesday night, I went to bed early, but it was already too late.

Before I lose those of you who want to avoid reading anything political right now, I get it. Really, I do.

But this isn’t another election night post-mortem about who won or lost. This is about something bigger — how we’re losing our grip on shared reality. It’s about how two essays, written 15 years apart, help explain why our collective imagination has become so warped that we can barely process political reality anymore.

Full disclosure: I may not be your typical news consumer. I don’t watch cable news and I mostly stay away from social media. I have carefully curated my media intake ever since listening to the renowned scholar and political activist Noam Chomsky speak when I was a student at The New School in 2001. I love PBS News Hour, but otherwise my news diet skews local, which in fact, comes from my time working here, as managing director at The Citizen.

But, wow, re-listening to Chomsky now feels like picking up a prophetic radio broadcast from the 1980s, except with the signal remixed by TikTok’s algorithm — it’s as if the core message is eerily prescient, but all the key players have been uncannily rearranged.

For an example, watch this four-and-half-minute video that explains the “Manufacturing Consent” model Chomsky created with Edward Herman in 1988. It still hums with truth, but the gatekeepers have been replaced by algorithms, the flak machines now run on retweets, and we’ve all become our own media elite.

My point is that I’m pretty methodical about what news I consume, and how I consume it. I try to read / listen to both sides (nod to Tangle News.) But, I’ve also come to appreciate that understanding media bias doesn’t mean surrendering to cynicism. In fact, the loudest voices telling us to distrust all traditional media are often selling their own carefully packaged version of reality. Yes, there’s wisdom in media skepticism, but there’s also wisdom in recognizing that even flawed institutions (eg: mainstream media) can deliver vital truths. The trick is learning to read the bias without letting it blind you to the facts beneath.

“A republic requires citizens; entertainment requires only an audience.” — Megan Garber

But even with all my careful filtering, my well-curated media diet couldn’t help but collide with the chaos of real-time political theater on election night. I was struck by how each screen and channel was offering its own version of reality, its own narrative of what was happening across America. Each felt simultaneously true and incomplete.

It was too much. I went to bed.

In the aftermath, I couldn’t stomach another hot take or think piece on what happened, or what to do next, or worst of all, how I should feel. Instead, my mind kept wandering back to the two essays I mentioned.

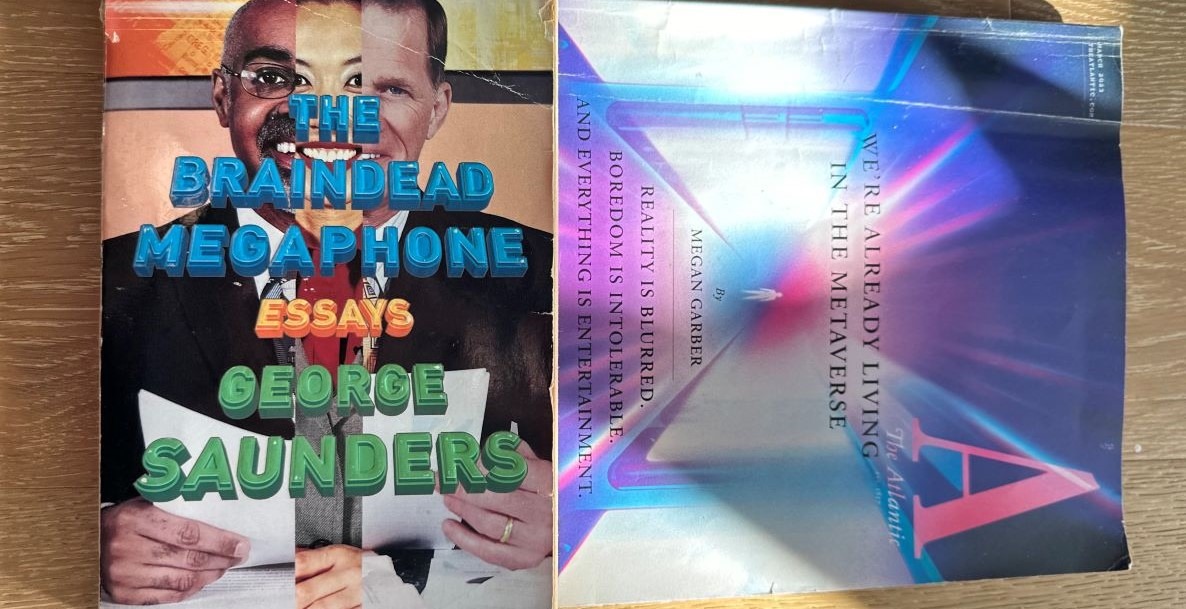

The Braindead Megaphone

The first essay is George Saunders’ The Braindead Megaphone, which was published as the title essay of his 2007 collection of nonfiction (in the days of the Iraq War), and on its surface it’s about media criticism — but really, it’s about how storytelling shapes our ability to imagine complexly.

Saunders sets it up like this: Imagine you’re at a party where everyone’s having these great little conversations. Then some guy shows up with a megaphone. He’s not the smartest person there, or the most interesting — but suddenly everyone’s talking about whatever he’s talking about, just because he’s the loudest voice in the room. People begin discussing what he’s discussing, using his phrases, adopting his worldview — not because he’s right, but because he’s unavoidable.

His main characteristic is his dominance. He crowds the other voices out. His rhetoric becomes the central rhetoric because of its unavoidability.

Saunders describes how

In the beginning, there’s a blank mind. Then that mind gets an idea in it, and the trouble begins, because the mind mistakes the idea for the world.

In an age of commercial media, these mistakes compound with devastating consequences. His party guest with a megaphone isn’t just loud — he’s rewriting the stories we tell ourselves about what’s possible. He goes on:

Mass media’s job is to provide this simulacra of the world, upon which we build our ideas. There’s another name for this simulacra-building: storytelling.

Megaphone Guy is a storyteller, but his stories are not so good. Or rather, his stories are limited. His stories have not had time to gestate — they go out too fast and to too broad an audience.

A culture’s ability to understand the world and itself is critical to its survival. But today we are led into the arena of public debate by seers whose main gift is their ability to compel people to continue to watch them.

Saunders recognized, even back in 2007, that this phenomena of sensationalistic, profit-seeking media isn’t necessarily new, but says:

I think we’re in an hour of special danger, if only because our technology has become so loud, slick, and seductive, its powers of self-critique so insufficient and glacial. The era of the jackboot is over: the forces that come for our decency, humor, and freedom will be extolling, in beautiful smooth voices, the virtue of decency, humor, and freedom.

We’re Already Living in the Metaverse

Which brings me to essay two, Megan Garber‘s We’re Already Living in the Metaverse, published in March, 2023 in The Atlantic. Garber argues that we’ve already created the immersive alternative reality that tech companies have been promising — not through VR headsets, but through our phones, screens, and social feeds. As the subtitle describes, “Reality is blurred. Boredom is intolerable. And everything is entertainment.”

Garber writes:

We will surrender ourselves to our entertainment. We will become so distracted and dazed by our fictions that we’ll lose our sense of what is real.

When we finish one series, the streaming platforms humbly suggest what we might like next. When the algorithm gets it right, we binge, disappearing into a fictional world for hours or even days at a time …

Social media, meanwhile, beckons from the same devices with its own promises of unlimited entertainment. Instagram users peer into the lives of friends and celebrities alike, and post their own touched-up, filtered story for others to consume.

Dwell in this environment long enough, and it becomes difficult to process the facts of the world through anything except entertainment.

Each invitation to be entertained reinforces an impulse: to seek diversion whenever possible, to avoid tedium at all costs, to privilege the dramatized version of events over the actual one … it is not shocking but entirely fitting that a game-show host and Twitter personality would become president of the United States.

Garber traces these developments through the way we’ve become “conditioned to expect that the news will instantaneously become entertainment.” For example, after the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, Quinta Brunson, the creator of Abbott Elementary shared how she received messages from fans that she write a school shooting story line into her comedy:

People are that deeply removed from demanding more from the politicians they’ve elected and are instead demanding “entertainment.”

Garber explains how we’ve come to live in multiple realities simultaneously, each with its own rules, language, and version of truth. With a nod to the prophetic social critic, Neil Postman, and his 1985 book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, Garber explains how he diagnosed the nation with a “vast descent into triviality,” and worried that “the distinction that informed all others — fact or fiction – would be obliterated in the haze.”

Garber also subscribes to Hannah Arendt’s studying of societies that were “held in the sway of totalitarian dictators” and how the “ideal subjects of such rule are not the committed believers in the cause. They are instead the people who come to believe in everything and nothing at all: people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction no longer exists.”

Simply put: “A republic requires citizens; entertainment requires only an audience.”

Reading these essays side by side, something clicks into place.

Perhaps that’s where we start? Not by shouting louder, or by swiping faster, but by sharing and seeking out the kind of stories that break through our forces of habit.

Our problem isn’t just that we’re divided — it’s that we’re losing our ability to imagine each other as real people. The technology we use every day isn’t helping us understand each other better; it’s just making the loudest, angriest voices easier to hear.

The challenge isn’t just that we’re divided, but that our very ability to imagine each other, to think complexly about our shared future, is being shaped by technologies that prioritize volume over understanding, conflict over complexity.

Garber shows us how this technological fragmentation has evolved beyond Saunders’ party guest with a megaphone. Now we’re all starring in our own personal reality shows, where algorithms feed us exactly what we want to hear and the line between politics and entertainment has completely vanished. Meanwhile, here’s the kicker:

We have never been able to share so much of ourselves. And, as study after study has shown, we have never felt more alone.

We’re not just listening to the wrong stories; we’re trapped in multiple, parallel storytelling machines.

The antidote

But there’s hope in recognition. As Saunders suggests:

What I propose as an antidote is simply: awareness of the Megaphonic tendency, and discussion of the same. Every well-thought-out rebuttal to dogma, every scrap of intelligent logic, every absurdist reduction of some bullying stance is the antidote …

We have met the enemy and he is us, yes, yes, but the fact that we have recognized ourselves as the enemy indicates we still have the ability to rise up and whip our own ass, so to speak: keep reminding ourselves that representations of the world are never the world itself.

Or as Garber puts it:

This could be how we lose the plot. This could be the somber finale of “America: The Limited Series.” Or perhaps it’s not too late for us to do what the denizens of the fictional dystopias could not: look up from the screens, seeing the world as it is and one another as we are.

Be transported by our entertainment but not bound by it.

I’ve walked around these last several days thinking a lot about our storytelling impulses, our fractured narratives, and if I’m being honest: Why do we bother? And I find myself returning to George Saunders one more time:

If the story is poor, or has an agenda, if it comes out of a paucity of imagination or is rushed, we imagine those other people as essentially unlike us: unknowable, inscrutable, inconvertible …

The best stories proceed from a mysterious truth-seeking impulse that narrative has when revised extensively; they are complex and baffling and ambiguous; they tend to make us slower to act, rather than quicker.

They make us more humble, cause us to empathize with people we don’t know, because they help us imagine these people, and when we imagine them — if the storytelling is good enough — we imagine them as being, essentially, like us.

Perhaps that’s where we start? Not by shouting louder, or by swiping faster, but by sharing and seeking out the kind of stories that break through our forces of habit— that make us pause, think, and remind us of our shared humanity.

David Williams is a former Managing Director at The Citizen and writes a weekly newsletter called A Short Distance Ahead.

The Citizen welcomes guest commentary from community members who represent that it is their own work and their own opinion based on true facts that they know firsthand.

![]() MORE ON THE ELECTION AFTERMATH

MORE ON THE ELECTION AFTERMATH