Outside the Liacouras Center last Tuesday, word spread that Governor Josh Shapiro — the opener for Kamala Harris’s first Philly campaign rally — had exited the stage, dashing hopes of late entry among the hundreds of people still standing in line. “I’ve invested three hours into this and I want to see if it’s worth something,” said a woman in line, to which a stranger replied, “It counts — maybe more than getting in.”

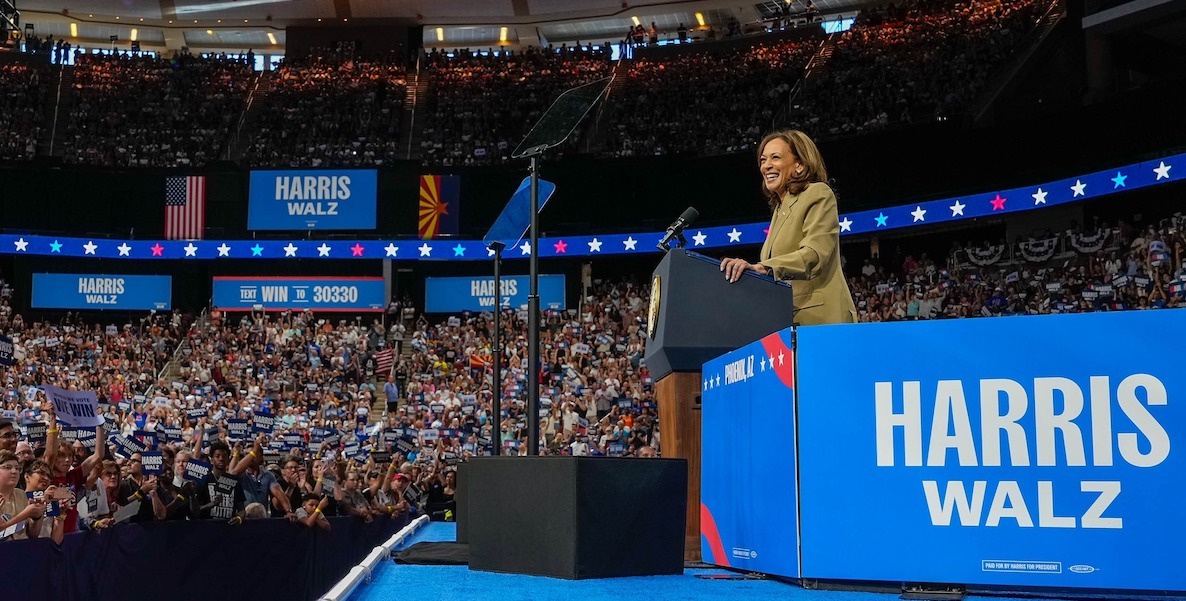

The message from Kamala Harris supporters was simple: Donald Trump couldn’t pull this overflow crowd, certainly not in North Philly.

In the three weeks since Joe Biden dropped out of the race, the mounting excitement for Kamala Harris as the Democratic nominee has been swiftly reflected in polls. According to new data released prior to last week’s event, Harris had grabbed or widened leads over Trump in several key swing-state demographics, including dramatic shifts among Hispanic and Black voters. The diversity of the Harris coalition was on full display among the throngs who gathered on Temple’s campus, too.

But there’s an irony surrounding these recent gains: Harris, since becoming the nominee, has carefully avoided talking about race, even when baited. It’s part of an early campaign strategy that the New Yorker’s Jay Caspian Kang described as, “don’t make any unforced errors, keep things vanilla, and eventually Trump or Vance will implode.”

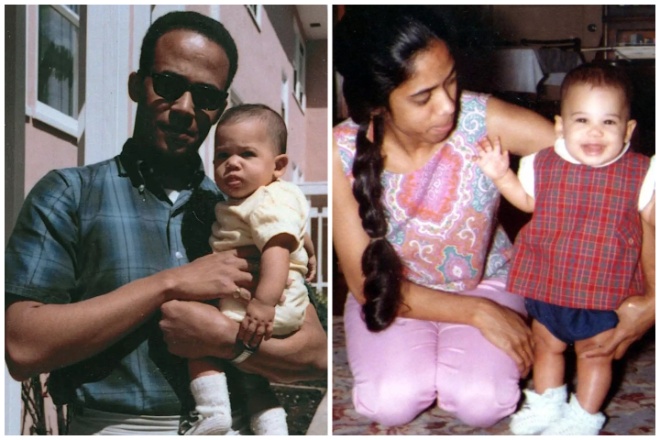

Only a week earlier, Trump made headlines by questioning the authenticity of Harris as a Black woman due to her mother’s South Asian ancestry, falsely insisting at a gathering of the National Association of Black Journalists that she only recently “became a Black person.” Trump then told Harris to pick one: “So I don’t know. Is she Indian or is she Black?”

Maybe it was a summer daydream, or the enthusiasm of the crowd, or the Shepard Fairey-style merchandise being sold, but my mind drifted back to 2008. Early in the primary race of that year, then-Senator Barack Obama was hesitant to wade into the topic of race. But then the Jeremiah Wright controversy erupted, and in March, Obama chose Philly as the site to quell the chatter. His now-famous “a more perfect union” speech put the spotlight on race in a way that captured the American imagination, while hitting back at the “commentators [who] have deemed me either “too Black” or “not Black enough,’” he said.

The speech was risky. It also arguably won him the election.

In the United States today, the multiracial population is growing three times faster than the country as a whole, and more than every monoracial group.

I wondered if Harris would pay homage. But instead, none of the televised speakers (Shapiro, Walz, Harris) brought up Trump’s remarks. Nobody invoked the fact that Harris would be the first Black woman, first South Asian woman, or first woman to lead the country. When the vice president briefly mentioned her own upbringing, she omitted her parents’ stories as immigrants from Jamaica and India. “The daughter of Oakland, California, raised by a working mother,” she said.

On the one hand, it may be a winning strategy. Some pollsters believe that Harris is better off sticking to issues over identity, pointing to the failures of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign. On the other hand, race is part of her story. In fact, her family’s multiracial, immigrant story fits neatly into an American narrative that could be beneficial to her campaign.

To not talk openly about her background would be to fail to live up to her legacy as a leader who reflects an America of the future.

There is no “side”

In the United States today, the multiracial population is growing three times faster than the country as a whole, and more than every monoracial group. This is both a byproduct of more interracial relationships and a burgeoning effort to recognize “mixed” as a shared identity. And yet the language around multiracialism rubs a lot of people the wrong way.

You can hear that frustration in Trump’s echo of ethnic absolutism — a philosophy that racial categories are fixed, inherent and essential to understanding a person. It’s a belief that was central to the founding of the country and the formation of the one-drop rule, which is the idea that a single Black ancestor makes you Black in America (and excludes you from being White).

I adhered to the one-drop rule from a young age. Though I was the son of a Polish-American mom, I identified as Black, like my father. But when I said I was Black, I often got weird looks. I had straight hair, light skin and ambiguous features. When I identified as mixed, I confronted stigmas, such as the idea that I was ashamed of being Black — when in reality, it was quite the opposite; I wished to recognize the privileges that came along with my experience and also have a word that reflected a life of being constantly asked, What are you?

Regardless, the ascendency of the mixed-race experience is a threat to the status quo. In his 2016 autobiography, Born A Crime, comedian Trevor Noah (whose experience growing up in South Africa was similar to what it was like in the United States under Jim Crow) described it like this:

In any society built on institutionalized racism, race mixing doesn’t merely challenge the system as unjust, it reveals the system as unsustainable and incoherent. Race mixing proves that races can mix, and in a lot of cases want to mix. Because a mixed person embodies that rebuke to the logic of the system, race mixing becomes a crime worse than treason.

In 2008, after reading Obama’s first autobiography and watching him win the election, there was a feeling of validation, even if Obama mostly identified as Black. There were parts of myself reflected in the president’s own search for identity. Except, once he became president, a lot of that nuance faded away. The American public displayed so much fear of a Black president that there was little room to consider his multiracial dimensions. The right began to label Obama as anti-White. Rush Limbaugh said that Obama’s “entire economic program is reparations.” And this happened in Obama’s first term in the White House, when he made a concerted effort to avoid talking about race.

But if Harris doesn’t talk about race herself, she risks having others, including her critics, graft their own agenda onto her. Since Trump’s comments to the Black journalists, for example, his supporters have accused Harris of “picking a side” — as if identifying with her Indian mother meant she had chosen to be Indian, not Black, or vice versa. But for people of mixed race, there often is no side; there is only the whole. And the whole — like America itself — is not as simple as Harris’s opponents would make it out to be.

Owning the story we tell

Last year, fellow journalist Daralyse Lyons and I released a podcast called On Being Biracial. We interviewed more than 30 people, some famous, some not, who had parents of differing races, but only a portion of whom identified as multiracial.

“When I was growing up, if you said you were mixed, it was a way of distancing yourself from Blackness,” said Mat Johnson, one of our interviewees. Johnson won the National Book Award for his novel Loving Day, which is set in Germantown, where he grew up. “Mixed didn’t exist back then,” he said. “You were just Black and not good at it.”

If Harris can find a way to affirm her biracial identity, on her own terms, she could be the face of a growing identity, which, by definition, cuts across traditional divides in the country — like a president should aim to do.

The world has changed a lot for mixed-race kids since Johnson was born in 1970, or when I was born in 1990, or even since 2008. Both Johnson and myself now identify as “Black and mixed,” for example. There are now children’s books and toys using similar labels. Feeling like you have to hide or amputate a piece of your identity in order to conform to age-old misconceptions of race in this country is slowly fading.

Trump tried to deny the possibility of a both-and existence for Harris, and by association, the lived experiences of more than 33 million people who identified as two or more races in the 2020 Census. (Until 2000, that option was not allowed.) If Harris can find a way to affirm her biracial identity, on her own terms, she could be the face of a growing identity, which, by definition, cuts across traditional divides in the country — like a president should aim to do.

While it makes sense for the Harris campaign to be cautious, the election, as it often does, could come down to who tells the best story. Barack Obama spun a good one in 2008. During his campaign speech in Philly, he offered up his own mixed ancestry as a symbol of what unifies America, which is that we contain multitudes as a nation: “seared into my genetic makeup the idea that this nation is more than the sum of its parts — that out of many, we are truly one.”

Harris can be a flagbearer for that message as well. Not only is she both Black and Indian, she’s a woman, the daughter of immigrants, the stepmother of a blended family, and the sum of many other identities, like so many Americans. Where else in the world can you get a candidate who embodies all of that?

![]() MORE ON THE 2024 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION

MORE ON THE 2024 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION