“Leaders are visionaries with a poorly developed sense of fear and no concept of the odds against them.They make the impossible happen.” —Robert Jarvik, scientist and entrepreneur

Last week, my insider-handicapping of the already-forming 2023 mayoral field prompted some interesting feedback. “You’re always championing disruption,” one reader wrote. “Why a list of all elected officials to lead us?” Another wrote: “How about a piece on who you would like to run?”

Besides one factual quibble—progressive grocer Jeff Brown is not an elected official—these are astute critiques, and got me thinking. My instinct, in the wake of disappointing outsider leaders that run the gamut from the orange-haired dude who shall not be named to Tom Wolf to Larry Krasner—is now to gravitate toward those who have practiced the discrete skill of politics: the building of coalitions, the artistry of compromise, the merging of managerial competence with stirring vision.

I don’t know for sure if any of these dream candidates would be stellar mayors—the office, like the presidency, reveals things about its inhabitants that are unforeseen. But all of these folks have bold vision, experience building and running things, and the potential for speaking hard truths.

But, as Michael Bloomberg’s ascension from the private sector in New York two decades ago demonstrated, who’s to say that those qualities only reside in those already inside the political game? After all, it could be argued that Philadelphia’s greatest roadblock in recent decades has been the curse of incrementalism, the inability of elected officials to widen the aperture of their lens in order to build something new.

At the very least, if we want something we’ve long not had here—an open and robust citywide debate on the future of Philadelphia—we ought to encourage all of our best and brightest to jump into that scrum. So, if last week was a pragmatic account of insider analysis, what follows is a pie-in-the-sky wishlist, using the Jarvik postulate as a barometer.

Here goes, with the caveat that most of these folks are probably too smart to want to be mayor.

JOHN FRY

Drexel University President

The running of a large urban university—with its necessary balancing of competing interests, its premium on policies of equity and inclusion, its daily demand for organizational competence—is a great training ground for leading a diverse city.

The running of a large urban university—with its necessary balancing of competing interests, its premium on policies of equity and inclusion, its daily demand for organizational competence—is a great training ground for leading a diverse city.

And the way Fry in particular does it points to a rationale for a Fry mayoralty. In over a decade at Drexel and, before that, as Franklin & Marshall president and as Penn’s steward of neighborhood transformation under then-President Judith Rodin, Fry has time and again demonstrated his chops as a de facto urban planner.

In the process, he’s shown himself to be a true communitarian—the political philosophy made popular in the 1990s that is all about finally bringing to life the Latin phrase on our currency, e pluribus unum: Out of the many, one. Both at Drexel and at Penn, Fry’s emphasis has long been on trying to make each institution a vital part of its community, on partnering with, rather than big-footing, neighbors and neighborhoods. He’s baked into Drexel a philosophy of civic engagement, turning it into one of the nation’s most preeminent university when it comes to playing a role in its city beyond the comfortable confines of its own campus.

And—how many actors on our public stage can you say this about?—when he speaks publicly, he never seems anything but reasonable. That sure would be a nice switcheroo, wouldn’t it?

One civic leader close to Fry tells me—surprisingly—that Fry hasn’t ruled out a mayoral candidacy.

One civic leader close to Fry tells me—surprisingly—that Fry hasn’t ruled out a mayoral candidacy. With so many crises at the exact same time, this moment in Philadelphia’s history is as fraught as we’ve seen, and crying out for the type of leadership we’ve seen from Fry.

RELATED: John Fry speaks with other university presidents at an event in 2017

![]()

JANE GOLDEN

Mural Arts Philadelphia Executive Director

Nearly a decade ago, I first threw out Jane Golden’s name as an unconventional candidate for mayor. Golden is a force of nature: an outsider by temperament who knows how to play the inside game, someone who has built something grand out of sheer tenacity and passion.

Nearly a decade ago, I first threw out Jane Golden’s name as an unconventional candidate for mayor. Golden is a force of nature: an outsider by temperament who knows how to play the inside game, someone who has built something grand out of sheer tenacity and passion.

She has alternately cajoled, bullied and caressed the bureaucracy and establishment on the way to building the Mural Arts Program into a world-class institution. And, like any artist, she’s always in the act of invention: about a decade ago, she decided to move “beyond the wall” and transformed Mural Arts from merely a mural-painting operation into an agency of social change.

Golden, a political science major at Stanford years ago, has long harbored the fantasy of running for office in her beloved Philadelphia. Her work is all about empowering communities and bringing the disparate Philadelphias together, and her palpable passion for the city would make her Philly’s greatest salesperson-in-chief this side of Ed Rendell.

How refreshing would it be to hear from an elected leader, as she once said to me: “Where are the solutions going to come from? They’re going to come because we’re fearless and because we embrace imagination and creativity.”

RELATED: Jane Golden on art as a tool for social change

![]()

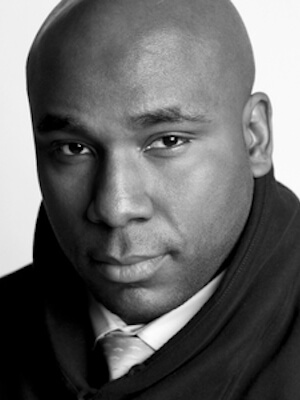

RYAN BOYER

Labor Leader

I don’t know Laborers’ District Council Business Manager Boyer well, but have watched him closely over the last few years. Recently, I moderated a panel he was on that had to do with Philadelphia’s growth strategies, and was struck again by his clear-headed outspokenness. In a town long dominated by labor leadership that hasn’t always been inclusive and has veered into thuggishness, Boyer has earned the moniker bestowed upon him by one big wig civic leader: “The conscience of the labor movement.”

I don’t know Laborers’ District Council Business Manager Boyer well, but have watched him closely over the last few years. Recently, I moderated a panel he was on that had to do with Philadelphia’s growth strategies, and was struck again by his clear-headed outspokenness. In a town long dominated by labor leadership that hasn’t always been inclusive and has veered into thuggishness, Boyer has earned the moniker bestowed upon him by one big wig civic leader: “The conscience of the labor movement.”

Boyer is bipartisan at a time when across-the-aisle outreach has become dangerously passe. He’s a proud backer of Mayor Kenney, but also had a longstanding close relationship with, for example, former State Senate Majority Leader Joe Scarnati. And he abhors tunnel vision, admitting in our recent panel discussion that what keeps him up at night are the job losses on the horizon wrought by automation and artificial intelligence.

Finally, Boyer’s story, in a town that revels in its rags-to-riches working class roots, is compelling. Born in North Philly, reared in union organizing, his story is a testament to the prospects of union mobility.

“When my dad got into union organizing, my family’s ascension was very quick,” Boyer once noted. “We moved from the projects to Germantown to Overbrook. I saw what a good union career could do.”

RELATED: Ryan Boyer on supporting Jim Kenney’s second mayoral bid

![]()

ALBA MARTINEZ

Private Sector Executive and Public Servant

Martinez’s is a name that has fallen off the Philly radar screen, but I raise it every time talk turns to the topic of unconventional mayoral candidates. She received high marks as commissioner of the Department of Human Services under then-Mayor John Street and then went on to run the United Way of Southeastern Pennsylvania.

Martinez’s is a name that has fallen off the Philly radar screen, but I raise it every time talk turns to the topic of unconventional mayoral candidates. She received high marks as commissioner of the Department of Human Services under then-Mayor John Street and then went on to run the United Way of Southeastern Pennsylvania.

Then she got something every politician should have: private-sector executive experience, having led Vanguard’s Education Markets Group, a $22 billion fund that provides low-cost investment options for families seeking to save for college, and its Global Talent Acquisition. Most recently, she founded Sol Impact Ventures, a fund committed to advancing wealth equality, Latino arts and culture.

“I’ve always wanted to be mayor, and I hope to run someday,” she once told me, and her personal story would fit the moment. Growing up in Puerto Rico, Martinez saw in her grandmother’s neighborhood example the literal definition of public service. “She was poor, but she shared so generously,” Martinez said in a speech at the Kline School of Law honoring her for her public service last December. “[My grandmother] was the first and best public servant that I’ve met…and she never got paid a dime for it.”

Martinez would be a breath of fresh air amid Philly’s acrid old-boys’ network: a gay Latina who lives in, and loves, the city. A Martinez candidacy would add quick-mindedness and a much-needed entrepreneurial spirit to the mix.

![]()

BILL GOLDERER

President and CEO of United Way of Greater Philadelphia and Southern New Jersey

Full disclosure: The boyish Golderer is a good friend, and supporter of The Citizen. Despite these questionable choices about who he hangs out with, few Philadelphians have exhibited his capacity to build new things and rethink old things.

Full disclosure: The boyish Golderer is a good friend, and supporter of The Citizen. Despite these questionable choices about who he hangs out with, few Philadelphians have exhibited his capacity to build new things and rethink old things.

Audaciousness has defined Golderer’s public work. He founded Broad Street Ministry on the premise that treating the homeless with dignity and respect was a practical solution. He enlisted the city’s restaurant and hospitality industry to partner on a five-star type of dining experience for those too long accustomed to soup kitchen cuisine. Now, he’s rebranded United Way around a much-needed, game-changing goal: Finally eradicating intergenerational poverty in the American city where it’s proven most stubborn.

In other words, Golderer flips the bird to incrementalism, and takes on bold, politically dicey causes. And he works well with others, partnering with everyone from Darrell Clarke to, well, me. And he’s got that ace in the hole: Jesus—“the Big Guy,” as he says—just may be on Team Golderer. Golderer is all heart, and it’s been a while since a courageous heart has driven political calculations in Philadelphia.

Alas, Golderer lives outside the city, so unless he’s got a pied-a-terre in Philly, he’d have to move within city limits, like, now in order to be ballot-eligible.

RELATED: Bill Golderer on solving the poverty problem

![]()

PHOEBE HADDON

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Chair

Remember that old ad slogan, “When E.F. Hutton speaks, people listen”? Well, it has long applied to Phoebe Haddon. She’s the former Chancellor of Rutgers University-Camden, where, like Fry, she turned her institution into an engine of local civic engagement and where her Bridging the Gap program provided groundbreaking tuition coverage for New Jersey’s working families.

Remember that old ad slogan, “When E.F. Hutton speaks, people listen”? Well, it has long applied to Phoebe Haddon. She’s the former Chancellor of Rutgers University-Camden, where, like Fry, she turned her institution into an engine of local civic engagement and where her Bridging the Gap program provided groundbreaking tuition coverage for New Jersey’s working families.

Under Haddon’s leadership as chair, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia (Fry also sits on its Board) has become noticeably more attuned to researching and exploring solutions to questions of economic inequality and mobility.

If we want something we’ve long not had here—an open and robust citywide debate on the future of Philadelphia—we ought to encourage all of our best and brightest to jump into that scrum.

That should come as no surprise, because everywhere she’s gone, Haddon has been an agent of change. Her commitment to equity has long been a feature of Haddon’s career—and life. Her mother, Ida Basette Haddon, was one of NASA’s women “computers” in Langley, Virginia, the gifted Black mathematicians without whom we might not have had a space program, as made famous in the 2016 Academy Award-nominated film Hidden Figures.

I doubt Haddon would ever run for political office—she’s too grounded, too sane and reasonable. But, given that literally every time you hear her speak, you find yourself nodding your head in agreement, there are worse candidates to fantasize about, no?

![]()

KEITH LEAPHART

Physician, Philanthropist and Entrepreneur

A couple of years ago, Philadelphia lost two civic giants: Gerry Lenfest and Citizen founding chairman Jeremy Nowak. The 46-year-old Leaphart was mentored by both men—Lenfest essentially adopted him— and has fast become arguably our best hope for the future of Philadelphia’s shared civic space.

A couple of years ago, Philadelphia lost two civic giants: Gerry Lenfest and Citizen founding chairman Jeremy Nowak. The 46-year-old Leaphart was mentored by both men—Lenfest essentially adopted him— and has fast become arguably our best hope for the future of Philadelphia’s shared civic space.

Leaphart had a difficult upbringing in West Oak Lane, where he was always driven by an entrepreneurial spirit. In an oft-told story, Leaphart met Lenfest in the late 1990s while running a commercial cleaning business that had the mogul’s Suburban Cable as a client. A dual MBA/MD student at the time, Leaphart gained Lenfest’s attention, and admiration, after a series of conversations in Suburban’s offices; more than a decade later, that led to Leaphart becoming chair of the Lenfest Foundation’s board of directors. There, he’s arguably done more to benefit kids who come from backgrounds like his than any other recent Philadelphian.

In the early aughts, Leaphart flirted with running for congress, and ended up serving in the Nutter administration, working on reentry solutions before it became a trendy policy area. Most recently, he’s launched an innovative app, Philanthropi, a tool Leaphart calls the “next generation employer benefit” that makes it easier for workers to contribute to causes they care about and for companies to track their impact and attract employees, as well.

Philanthropi embodies Leaphart’s unique strengths: He rethinks old processes, but never in an off-putting way. He reforms, but he doesn’t antagonize. In all he does, he works with the establishment while nudging it toward change. Imagine a mayor who, everyday, cajoles Philadelphia into rethinking itself.

RELATED: More on Philanthropi

![]()

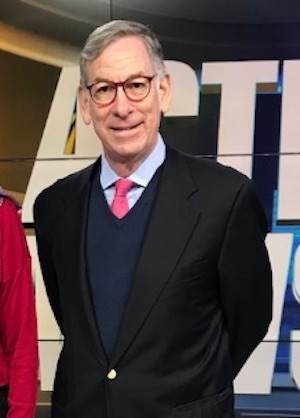

SAM KATZ

Businessman and Documentarian

Before Sam Katz remade himself as Philadelphia’s premiere historical documentarian, he was a three-time candidate for mayor—the job he has coveted since he was 7 years old and met legendary then-Mayor Richardson Dilworth.

Before Sam Katz remade himself as Philadelphia’s premiere historical documentarian, he was a three-time candidate for mayor—the job he has coveted since he was 7 years old and met legendary then-Mayor Richardson Dilworth.

In 1999, Katz, then a Republican, ran for mayor against John Street, in one of the closest and smartest campaigns in recent memory. The two candidates traversed the city, debating the issues, laying out their respective visions, asking each other questions, and questioning each other’s answers. In the end, Street won by a mere 8,000 votes of 425,000 cast, but both candidates professed their love for their city and each other. (Their rematch in 2003 became more divisive after an FBI bug was found in Street’s office.)

Katz was once the driving force behind influential Public Financial Management, the municipal finance firm that wrote the economic recovery plan for Ed Rendell in the early ‘90s. And he remains a fount of knowledge when it comes to managing cities and economic development. He’s 70 now, so it’s unlikely he’d dive back into the political fray, but if he did, you could imagine millennials loving him, not least because he was busted a few years ago for carrying a few joints onboard a flight to Florida for a fishing trip: “The kinds of posts I saw on Facebook, people saying I have ‘street cred’ or I’m ‘cool,’ I never spent a day in my life being cool,” he said at the time. “But I was cool last Thursday.”

Finally, if Katz’s voice found a way into a mayoral race, so would Street’s —the two have a fun, buddy-movie type of relationship these days, and there’s a lot of political wisdom in that pairing. Moreover, Katz has forgotten more Philly history than any of us will ever know. Once, when I asked for his diagnosis about what ails the culture of Philly politics, he introduced me to the cautionary tale of Smedley Butler.

Butler’s precipitous fall prompted the war hero to remark, “Cleaning up Philadelphia was worse than any battle I was ever in.”

Butler was a Marine Corps Major General and, at the time of his 1940 death, the most decorated Marine in United States history, one of only 19 men to receive the Medal of Honor twice. In 1924, during the height of Prohibition, Butler came to Philadelphia to become the city’s Director of Public Safety and announced he was going to clean up the famously corrupt police and fire departments. He assaulted the city’s go-along-to-get-along culture. He replaced corrupt cops, raided speakeasies, and took on bootlegging, prostitution, gambling and political corruption. He even set his sights on the city’s elite, raiding the Ritz-Carlton and Union League.

After less than two years in office, Butler was run out of town by that era’s ruling class; then-Mayor W. Freehand Kendrick brilliantly spun it: “I had the guts to bring General Butler to Philadelphia and I have the guts to fire him.” Butler’s precipitous fall prompted the war hero to remark, “Cleaning up Philadelphia was worse than any battle I was ever in.”

To Katz, who often says that “you can’t envision where you want to go if you have no idea where you’ve been,” there can be no reforming of Philadelphia transactionalism without knowing how deeply embedded insiderism has long been here. He no longer qualifies as a young disruptor, but Sam Katz’s public life and documentaries have all been about changing moribund institutions in order to serve the common good.

I don’t know for sure if any of the aforementioned dream candidates would be stellar mayors—the office, like the presidency, reveals things about its inhabitants that are unforeseen. But all of these folks pass the Jarvik test. All have bold vision, experience building and running things (I am so over electing legislators to chief executive positions!), and the potential for speaking hard truths, to us and to the keepers of our town’s same-old, same-old.

Feel free to quibble with this list, but indulge this one final, provocative fantasy: Let’s empty out City Hall and turn it over to this list. Say to them, Okay, guys, we don’t care who serves as what, but you become our government. Whatta ya got? Isn’t it likely that what we get will at least be better than what we have?

![]()

RELATED