Their parents weren’t happy. When Danny Cabrera graduated Penn a year ago and told his parents he wouldn’t be continuing on to grad school, they were disappointed that his long planned-for PhD wasn’t going to happen. When Ricardo Solorzano told his parents that he wouldn’t be going to med school, they had a tough time understanding: Who doesn’t want to become a doctor?

“They were pissed,” remembers Cabrera, laughing. “I don’t think our parents will be happy until we can eat a real meal more than twice a week.”

Instead, the two friends, who had attended Miami Dade Community College together before transferring to Penn, decided to keep doing what they’d been doing in their makeshift lab in Solorzano’s apartment above New Deck Tavern, on Sansom Street. While fellow students below drank draft beer and ate fish and chips, they were upstairs, building a 3-D printer capable of printing… human tissue.

“This started in our dorm room,” Cabrera recalls. “We’re lucky the FBI didn’t get wind of it and think we were doing some bio-terrorism experiments. It was a really fun time. Really stressful, too.”

They had no money. In June, for Cabrera’s 22nd birthday, Solarzano couldn’t afford a cake. So he stuck a candle in an apple and offered it to his bro. “Happy birthday,” he said.

“This started in our dorm room,” says Cabrera, 22. “We’re lucky the FBI didn’t get wind of it and think we were doing some bio-terrorism experiments.”

One year later, Cabrera and Solarzano are co-founders of BioBots, which beat out 48 other startups to win the innovation prize at last month’s South by Southwest music, film and tech festival. And they are $200,000 in to their goal of raising $1.5 million: changing medical research—and medicine—as we know it.

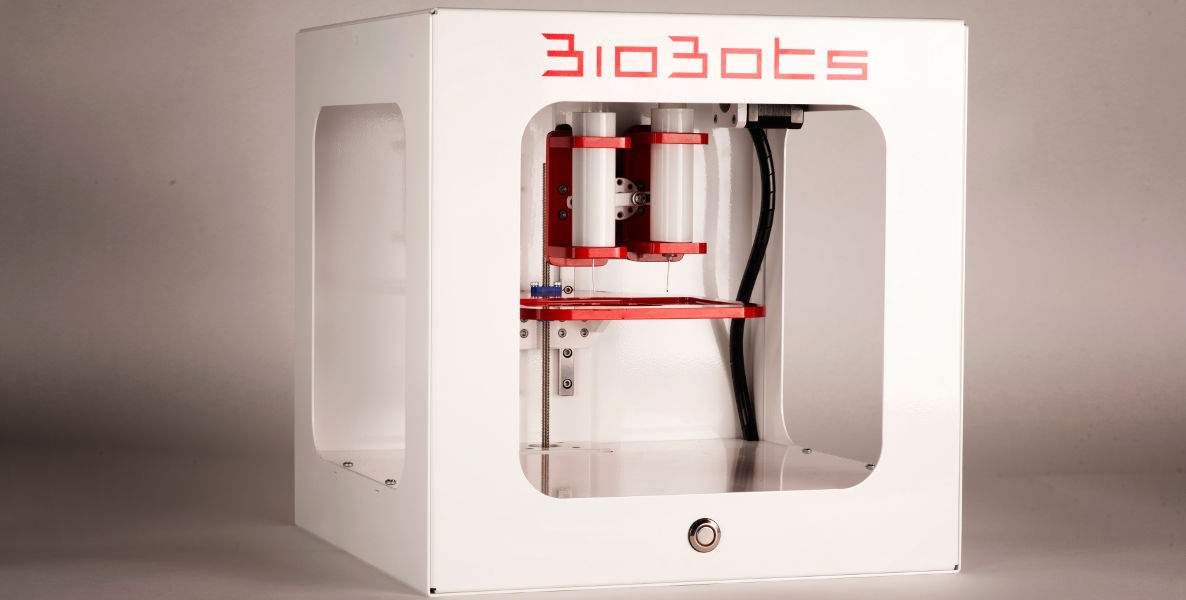

Their product—the BioBot 1— might do for bioprinting what the PC did for computing. At a low cost of $5,000, the desktop-size printer gives university research labs and medical device companies the ability to produce 3D organs with human cells in their own labs.

What does this mean? Cabrera’s research found that it costs over $1 billion dollars to bring a new pharmaceutical drug to market and that only one of every 5,000 drugs ever even make it that far. Why? A disproportionate number of once-promising drugs fall out amid late stage problems encountered in the animal-testing phase. “I said, ‘What if we could build a device that revealed a drug’s failures earlier?” Cabrera says. “What if we could pinpoint false positives earlier?”

BioBot’s customers design the tissue or body part they need on a 3D program. Then, they pick an “ink” from a variety of what BioBot calls “bio-compatible” materials, like collagen, gelatin or fibrin. Finally, they push print—and the result is a workable, testable human body part—like a cartilage knee cap. Or, eventually, the scaffold for a new heart. Or an ear.

The idea first gained traction when, as undergrads, Cabrera’s interest in computer science and biology combined with Solarzano’s passion for engineering. They presented their big idea at the International Genetically Engineered Machines competition, a worldwide smackdown between the best and brightest university biology students. They won.

The audacious goal is to end the wait list for organ donation. Imagine custom printing organs for implantation as the need arises.

At the time, it hadn’t been their goal to sell their technology to Big Pharma or major research institutions. Initially, Cabrera thought the best opportunity to effect widespread change would be in “bio-hacking:” A believer in open source technology, he envisioned directly giving you and I the tools to produce our own living organisms. In that sense, he’d empower us to be life-force hackers, seeing it as akin to the way computer hackers in the 1970s hacked their way to innovation.

“We thought we could have a consumer effect, using tech to build organs and tissues for implantation,” Cabrera recalls. “But we learned the space wasn’t there yet.”

Things took off late last summer, when they were accepted into the DreamIt Health accelerator. “That got us out of the apartment, and around really smart people,” Cabrera says. Suddenly, mentors were interested. Investors were intrigued. An elevator pitch was honed. After DreamIt, BioBots moved to NextFab, an innovation studio and co-working space on Washington Avenue, where they finally have a real office.

Yesterday, Cabrera was calling from Interphex in New York, one of the biggest pharma industry exhibitor shows in the world. Sales of the BioBot 1 are currently in double digits; purchasers are using the printer to build human tissue in the lab with the goal of replacing tissue in the human body. Cabrera and Solorzano’s first-round $1.5 million raise has enabled them to hire a software designer and tissue engineer.

But the most audacious goal is yet to come. Cabrera says it may be years out, but their eye is on the prize that Cabrera refers to as their “Holy Grail:” Ending the wait-list for organ transplantation. Imagine, custom printing organs for implantation in real time, as the need arises. Cartilage and bone will come soon. “Hearts and liver?” Cabrera asks. “I’m not sure how long. Maybe 10 years.”

That would place him and Solorzano at all of 32.