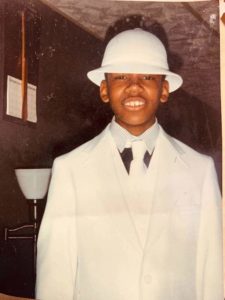

Go ahead, take a look to your right at the pic of a young Darrell Alston, age 10, in his precious, pint-sized, three-piece suit.

Take in the smile, that sparkle in his eyes, that suit. Adorable, sure, but there’s something else, something extra about him, right? A magnetism, you could call it.

So you may not be totally surprised to learn that that fashion-loving little kid would go on to create a high-end sneaker and apparel line, the Philly-based, new-to-the-market Bungee Oblečení.

But first, on his way to getting there, he was a star in other realms: as a running back on the football field at Conestoga High School, college options within arm’s reach. And then on stages around the country, as a musically gifted rapper who, in lieu of playing college ball, signed to a record label in 1994, opening for acts like LL Cool J and Lil’ Kim. (His rap name: 4th Quarter. “The D for Darrell is the fourth letter in the alphabet, and when I came up with the name I only had a quarter in my pocket,” he explains. He vowed to never be broke again.)

“My dad always taught me that I had to play better than everyone else to be noticed on the field, so I always gave 110 percent,” Alston, a Paoli native, says.

But the high life that comes with the rap world? It also often comes with high rollers, too, and to keep up with them, Alston turned to the one path he’d always known his hardworking father, the one who taped all of his childhood football games and took him to Eagles games, most loathed: He started selling drugs.

Then he got caught, and spent 11 years in and out of the prison system. During that time, Alston felt the crushing blow of being apart from his family when his doting grandfather died. And his own father, Alston says, started to despise him.

But something else happened while Alston was incarcerated: When he’d go to the gym at Graterford Prison, a mural of former Graterford inmate and boxing legend Bernard Hopkins staring back at him, he started to draw. Not just mindless doodles, but designs for sneakers.

More than 200 of them.

Neighborhood networking

Released from prison in 2012 and on probation for another four years, Alston started working at barbershops in Wayne and Paoli, while having prototypes of several of his sneaker designs made, albeit with cheap materials and lackluster craftsmanship.

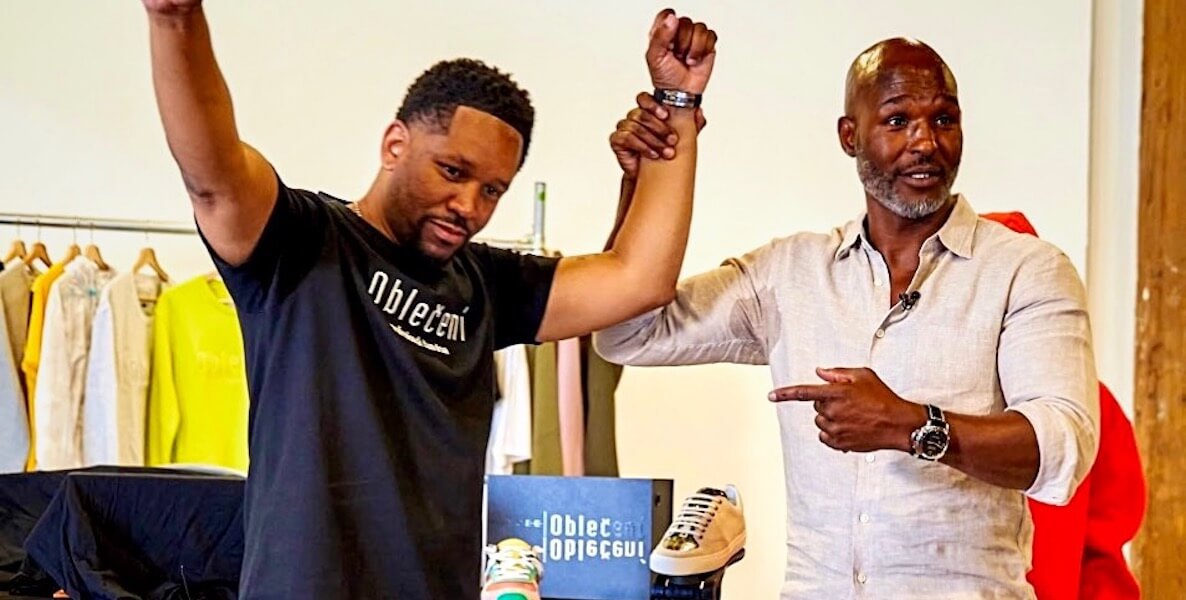

Wearing them at work, clients took note. One of the designs paid homage to the classic boxing sneaker silhouette, that high-top, fitted boot; it had been inspired by the Graterford mural of Hopkins. So when a barbershop client who—get this—just so happened to be meeting with Hopkins offered to introduce Alston to the champ, naturally Alston jumped at the chance.

He wanted to get his sneakers in front of Hopkins, but mostly? He just wanted to soak up advice about turning around his life.

Given three minutes to pitch, Hopkins was dismissive. “I’m 50—I’d never wear these!” he told a dejected Alston. But when the boxing great found out that both men had spent time at two of the same prisons—Graterford, and SCI Dallas—Hopkins instantaneously softened.

He decided to take Alston under his wing, wearing Alston’s early prototypes in photos and videos, but also calling Alston nearly every day, to hit the gym and rally him to be successful. He guided him through the men’s shoe department at Saks, showing him the kinds of details and materials that appeal to high-end shoppers. Today, Alston says that Hopkins is like an uncle figure.

It was another chance encounter at the barbershop that led Alston to where he is today, poised to launch his new line of sneakers and in talks with two department stores to stock them.

Doors to opportunity

In August 2019, someone at the barbershop offered Alston a free TV in exchange for hauling it out of his boss’ Main Line home. While there, that boss took note of Alston’s kicks and offered to introduce him to potential investors.

“The first time I was introduced to someone who was possibly interested in investing in my sneakers, I felt obligated to start our conversation by letting him know I’d gone to prison,” Alston says. His forthrightness came from a place of shame: He was, and remains, deeply embarrassed about his incarceration, and didn’t want to bring anyone else down with him by not being totally transparent.

“My dad always taught me that I had to play better than everyone else to be noticed on the field, so I always gave 110 percent,” Alston says.

“You didn’t have a lawyer, did you?” the would-be investor said, when Alston told him he’d been convicted of dealing drugs.

“No,” Alston conceded. “How’d you know?”

“Those kinds of charges don’t land most people with lawyers in prison.”

With no judgement passed, the conversation proceeded; that man introduced Alston to a bigger team of potential investors (all of whom insist on remaining silent, to let Alston shine). Their financial backing allowed Alston to switch production to Italy and Portugal and even Philly, for higher-quality production, and to incorporate materials like premium leather and ostrich. “I did a lot of research and some trial-and-error with a few manufacturers before I found the perfect fit for Bungee,” he explains of his doggedness, his determination to learn the ins and outs of the competitive footwear business.

Kicking into high gear

Bungee Oblečení has had several unofficial soft launches, with the pandemic relegating 2020 to a development- and planning-focused year. But this week it’s kicking into high gear with the launch of the Oblečení 360. Riffing off of the original boxing sneaker Alston designed all those years ago at Graterford (closed in 2018, and replaced by SCI Phoenix), it’s a high-top made of premium leather and mesh, the kind of high-end design that even Bernard Hopkins would, and does, proudly wear. At $350, it’s meant for a designer clientele.

There’s also apparel and other footwear for men and women: cropped hoodies, logo tees, designer sweatpants. Merchandise is sold through bungeebrand.com, as well as two stores in Philly (Blue Sole Shoes on Chestnut and Gate2-15 on South Street).

Naturally, it’s too early to report on financials one week into launch, but there are promising signs: Retailers that Alston could only dream of shopping at as a kid (and which he has to keep confidential until contracts are signed), are now reaching out to him about carrying the line. Last weekend he received national TV coverage from The Today Show. And he’s on the precipice of expanding his staff, headquartered in Kensington, from 6 to 15 by the end of 2021.

“In a few years, I expect Bungee Oblečení to branch out to more than just sneakers and apparel. Our design team is hard at work creating everything from watches and handbags to glasses and suits. In a few years, Bungee Oblečení will be known for being a full luxury brand,” he says.

Sharing his story

For now, like all successful entrepreneurs, Alston works nonstop, often falling asleep at night with his laptop open to his latest designs. But unlike other entrepreneurs, Alston has another mission, as well: to use his role for good. In an early conversation with his investors, one of them asked if he would be willing to tell his story, as part of promoting his business. Alston hesitated. He hadn’t wanted to go that public with the past he was ashamed of.

But then he thought about the kids in neighborhoods all around the country where, as in his own community, men are regularly welcomed home from prison with parties, and looked up to for their proverbial badge of honor. Where neighbors going off to college are derided as corny.

He realized that if he was once again on the precipice of having a public platform, he could have a positive impact on young people—after all, he could connect to kids who’d been like him. “I was one of those kids where, if a firefighter or policeman or someone like that came to speak to us, I just couldn’t relate to that person because they didn’t look like me, they didn’t act like me, they weren’t from my neighborhood,” he says.

“When I first got out of prison, I didn’t know how to work a cell phone, I didn’t know how to pump gas, I didn’t know anything about social media, because there was no Facebook when I went to jail,” Alston says. “Just imagine being a grown adult, coming home from prison, and you don’t know how to do anything.”

In fact, Alston’s story shaped the name of his brand, Bungee Oblečení: Bungee refers to the ups and downs of Alston’s life—and everyone else’s. (You don’t have to have gone to prison to have experienced highs and lows.) Oblečení, added to connote an air of sophistication, means clothes in Czech.

“What I try to portray to kids now is that if you’re fortunate enough to live the next 10 years, you’re gonna experience things if you get in trouble where you’re not going to be able to find a house or a place to live, because people are not going to want you in their neighborhood or their house if you have a criminal background,” he says. “You’re not going to be able to find a job. You’re going to be in and out of jail. You’re going to lose family members while you’re in and out of jail, you’re gonna lose that girlfriend on your arm or boyfriend. When you break it down to them like that, it’s a different way of feeling. And I can explain to them exactly what happened to me and how I felt in those situations.”

Making systemic change

Alston intends, in the future, to hire returning citizens like himself, but also people from all kinds of marginalized backgrounds. “I met the most creative people of my life while incarcerated. But I don’t want to be that business that only hires people who look like me or who have been in the same positions as me,” he says. “Because there are kids that are out there who graduate from high school and just can’t afford to go to college. Or people who went to college but couldn’t afford to stay, or their grades weren’t good enough to stay. I’m willing to bring people on and learn with them. If you’re talented enough to make it, then I want you.”

He also wants to be a voice for criminal justice reform, to eliminate some of the injustice and, well, arbitrariness he (and, famously, others like Meek Mill) experienced.

“There have been plenty of judges who I’d hear say something like, How many birds are out there on that branch? And I’d be like: three. And they’d say, Ok, well you’re doing three years.” How can they get away with that, he wondered. And how can probation officers, who you’d think would be there to help you navigate the world, punish you, send you back to prison for seemingly ambiguous infractions?

He also wants to highlight the need to provide meaningful mental health support for men like him.

“There should be some kind of therapy [for returning citizens]. To this day, I still have nightmares about being in prison, and I’ve been home for years now. It’s very devastating, and people have such a bravado when they come home from prison that they don’t want people to know they’re experiencing any of that. So we kind of just go on without [therapy],” he says.

“I‘m just thankful that he’s alive to actually see me make the transition from where I was, to what I am today,” Alston says. “I’m extremely thankful for that.”

Yes, there are programs for returning citizens, but none, he says, address the day-to-day obstacles so many former inmates really face. “When I first got out of prison, I didn’t know how to work a cell phone, I didn’t know how to pump gas, I didn’t know anything about social media, because there was no Facebook when I went to jail. Just imagine being a grown adult, coming home from prison, and you don’t know how to do anything.”

As he thinks about making systemic change, he remains focused on local change, on getting through to young people, in particular.

The last time he spoke to a group of kids, he told them how he lost his grandfather while he was incarcerated; he cried when telling the story, and it hit the young people hard. “They knew that they had loved ones, too, who they could possibly lose if they were to go to prison,” Alston says. He also makes clear that those kids they’re calling “corny” now? They’re going to run the world someday, and it’s time to respect, not bully, them.

The last time he spoke to a group of kids, he told them how he lost his grandfather while he was incarcerated; he cried when telling the story, and it hit the young people hard. “They knew that they had loved ones, too, who they could possibly lose if they were to go to prison,” Alston says. He also makes clear that those kids they’re calling “corny” now? They’re going to run the world someday, and it’s time to respect, not bully, them.

As for Alston’s loved ones today, he says that while he and his father have had a strained relationship, they’re working on their bond. “I‘m just thankful that he’s alive to actually see me make the transition from where I was, to what I am today,” Alston says. “I’m extremely thankful for that.”

Things are heading in the right direction: In fact today, the elder Alston proudly wears Bungee Oblečenís, made by the son who’s proving to his father, his family, and the world that even with all of the “bungee”-ing, it’s never too late to turn around your life.

The Citizen is one of 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow the project on Twitter @BrokeInPhilly.